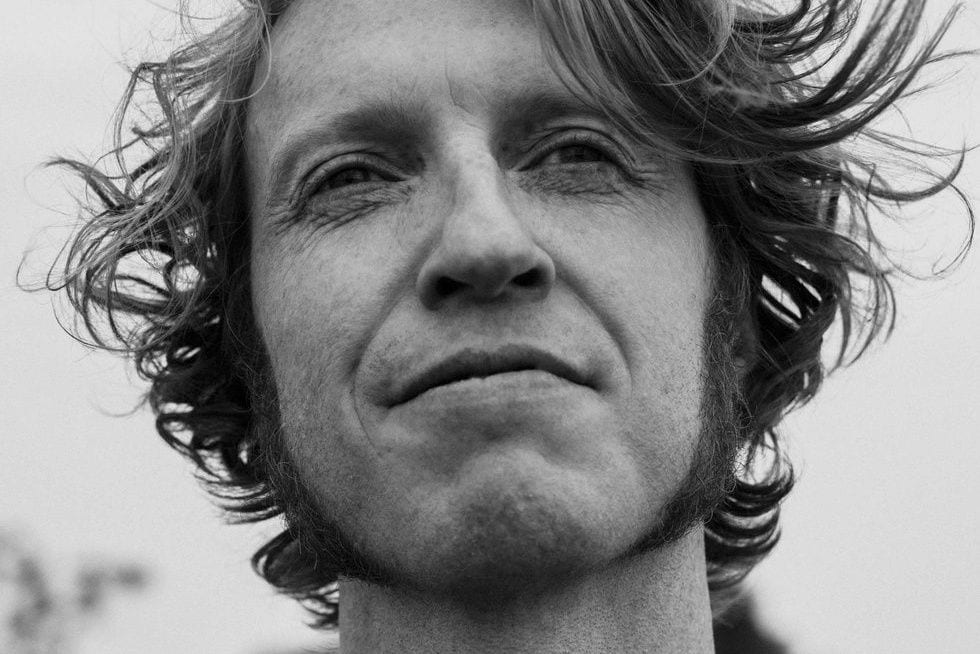

For some artists, a project on the scale of Richard Reed Parry‘s Quiet River of Dust, would be ambitious and sound that way as well. Instead, Parry, a core member of Arcade Fire, has delivered a typically effortless-sounding collection of songs via the first two of what he says will ultimately be four albums. Quiet River of Dust Vol. 2: That Side of the River arrived earlier this year, not as much announcing itself as seeping into the musical stream quietly, without bluster.

As with its predecessor and Parry‘s larger body of work, including the gorgeous Music For Heart and Breath (2014), the material is meditative, multi-layered but never impossibly dense. It is quiet without being non-descript, dynamic without being overbearing and, in its way, deeply personal.

Inspired in part by a stay he had at a Japanese monastery, the compositions are influenced by Eastern philosophy, mindfulness. “Lost in the Waves” tells the story of a boy who travels to the beach with his parents; when they fall asleep, he walks into the water and experiences a fundamental transformation.

Joining Parry on this journey are longtime friends Aaron and Bryce Dessner (the National), Laurel Sprengelmeyer (Little Scream), Stef Schneider (Bell Orchestre), Yuka Honda (Cibo Matto) and Tchad Blake, known for his singular mixing and engineering. Dallas Good (the Sadies) and Amedo Pace (Blonde Redhead) appear as well. Parry also called upon members of Friends of Fiddler’s Green, the band in which his late father, David Parry, was a longtime member.

The music heard across these two volumes is a testament to Parry’s depth as a composer and multi-instrumentalist but also provides a sense of peaceful resolve in a world often absorbed by noise and chaos.

Parry recently spoke with PopMatters about his creative process, his musical upbringing and his relationship with the Desnner brothers.

Are you typically prolific?

It’s typical for me to be generating music all the time. Or at least a lot of the time but without doing it willfully. [Laughs.] I do it as it comes. As the spirit moves me. I generally don’t think, “this is an album” or “this is what I want to do or am trying to do”. It exists for its own sake up to a certain point. Then, at that point, it becomes clear, “Oh, I’m making an album? What does this album need?”

I’m assuming you have a home studio. It sounds like maybe you get up in the morning and start tinkering right away.

My studio isn’t in my home anymore. It was when I started these records. It is typical. I really like to feel like that there are no boundaries. No walls. I just want to see where it will go. These albums feel like they assembled themselves.

Water, cups, waves are all recurring throughout the album. Is that something that revealed itself as you were working on the music?

It did, but then, at a certain point, I realized that I was working within the confines of a certain narrative. Or that there was a loosely-packed story that I was looking at through the prism of fluctuating viewpoints. Once I became aware of that, I started playing into it more. Then I started writing into it in some ways. I was just writing to explore.

This time out you worked with members of your late father’s band, Friends of Fiddler’s Green. Had you stayed in touch with them this whole time?

They’re like family. It’s not even a case of trying to stay in touch. You’re just in touch permanently even if you don’t talk to them for a couple of years.

It had to be meaningful for you to have them come and play your music.

Super meaningful. That is what I grew up knowing music to be. That was my musical reality. Being at their shows and being hauled around to folk festivals and learning all the songs that they sang. All of them were archival minds that all knew thousands of songs. We grew up hearing what they sang and heard.

I had them come in for two different things: One was for singing, the other was for playing. It felt like it was a specific thing that they did that didn’t take any effort to get them to do. [Laughs.] I also ended up using it in ways that I hadn’t planned. I had them sing on one song and then play on another song. They’re on Vol. 1, but then I took the vocals they sang and turned them into a kind of coda at the end. Then I took parts and turned that into an overture for this album.

What was your first exposure to either classical or avant-garde music? Did that come through your parents?

I took piano lessons when I was little, so there were seeds of the avant-garde in that. The moment you play a Bartok piece, something so heavy and unique and different, and it steps outside the feelings of music that you’re exposed to as a young person [opens a door]. But at folk festivals, there would be Senegalese drummers, or there’d be First Nations folks singing or doing drum pieces. There are so many different cultural traditions of the world that one could grow up being oblivious to that I got exposed to at a young age just by being in that environment.

It didn’t feel like I was discovering avant-garde music. It didn’t feel like a threat. It never felt like I was straying off of a path or making a radical break. I was just always pulled toward whatever music felt intriguing or compelling or beautiful. The more you hear things that qualify as avant-garde, the more they appeal to you just because they’re less of a known feeling and they feel more exciting and fresh, like they have something new to offer.

Did you lean toward more nuanced pop music as a teenager?

I didn’t like a lot of radio pop music as a teenager. Radio as a medium is so abstract now. Pop radio right now is such a dire affair compared to even what we had in the ’90s. Madonna or ’90s-era Prince or even Genesis, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Nirvana from that time, whatever, stuff that I wasn’t convinced about at the time, now I’m, like, “There was some pretty good stuff happening on radio then.” I was really into the Who, Jane’s Addiction, Public Enemy. Nirvana and Pearl Jam. It was in that weird ’90s time of, “Is this mainstream? Is it punk rock?” It shook things up and made some interesting music more boring and some boring music more interesting.

I took a trip recently and only had terrestrial radio in the car. A Foreigner song came on, and I thought, “Wow! This sounds amazing!” Ten years ago I would have never reached for Foreigner.

Totally, compared to your middle-of-the-road shit rock that happens now. Quantized, ProTools. Meatgrinder stuff. They just released this Prince album with songs that he wrote for other people [Originals]. I just rediscovered that song “Love… Thy Will Be Done” that he gave to Martika. I remember it so well now from the ’90s. I’m so completely smitten with that song right now. His version is basically her version but she re-sang all the parts. It’s so incredible, such a good song, and I dream of a song turning up like that now on the radio. That would be such a cool, fresh breeze. At the time, I didn’t find it remarkable. I didn’t dislike it. I know a lot of the words so I must have listened to it a lot, but I didn’t think about it or want to buy the record. Now I think, “What an incredible piece of art!”

How did your relationship with the National start?

I became aware of them around the time Alligator came out. Arcade Fire happened to be playing on different floors of the same venue in Amsterdam in 2004. We made friends. I watched their soundcheck. Me and Bryce [Dessner] were immediately talking about how we both made instrumental hybrid chamber rock music. We were aware of each other’s other bands, Bell Orchestre and Clogs. We said, “We should play a show together; do something sometime.” That was that.

I forget when we next came into each other’s orbit, but at some point, he invited Bell Orchestre to come and play MusicNOW, this festival he started in Cincinnati that’s really awesome. It’s 12 or 13 years on. Then Bell Orchestre and Clogs toured together. He’s one of my best friends now. Aaron [Dessner] is near and dear to me as well. I don’t remember the first time we collaborated on music, though. It might have been through working on Sufjan’s Christmas music.

High Violet was the first time I worked with them in a big way. In the end, it was organic. It’s a really easy relationship.

How meaningful was it for you to have Kronos Quartet be part of the Music For Heart and Breath album?

Pretty meaningful. I aspired to make records of that caliber, even though I wasn’t classically trained in the same way. Their records Early Music and Nuevo made a huge impact on me. It was, like, “Ah, this is what you can do.” They paid attention to the record itself. It wasn’t just a document of a properly-played piece. They were paying attention to the recording aesthetics and the production value. They weren’t afraid of doing things that would enhance the listening experience. I really appreciated that.

When I was making Bell Orchestre records that was an influence on me. Processing strings to make them sound really dirty and broken and distorted, a string quartet doing that impacted me and impacted Arcade Fire as well.

They premiered the first Music For Heart and Breath at Bryce’s festival when they were artists-in-residence one year. To have heavyweights like that wanting to play my music was amazing. They’re so open-minded and great collaborators. They set the template for what string quartets would become in a lot of ways.

You also worked with yMusic, which does something similar. I can turn on the TV and see them playing with Paul Simon, but then they’re doing something completely different the next week.

Very much picking up that spirit of a new music ensemble doing anything it wants to. Those old divisions between genres have readjusted themselves. They didn’t totally disappear, but they’re recalibrated.

When do you see the next volumes of Quiet River of Dust emerging?

They’ll be out once they’re done! [Laughs.] It won’t be eight years in the making because I’m already well into recording some of what will be next. There’s more of a framework around it than there was before.