By the 1930s, American jazz had graduated to the sound of the big bands performing swing music. What had started as small ensembles of five or so performers playing in brothels and speakeasies, jazz was now showcased in large venues with a much fuller complement of musicians. Jazz hit its commercial apex during this “swing era” and was heard by millions on radio and records, and not just in America.

For a world weary from having just survived an economic depression only to end up in another global war, the sound coming over the speakers was a much-needed tonic. With fascism on the rise seemingly everywhere, America was becoming the last beacon of hope. Nothing sounded more confident and inspiring than a large group of virtuoso musicians banging out a big sound full of swagger and bravado. In this most popular era for jazz, swing became a powerful export sold to people from every corner of the globe who were eager to buy into the new American mystique.

For a host of reasons, big band swing would eventually collapse in on itself after the war years ended in the mid-1940s. The weight of its business model and its constraint on creativity contributed to this, but what really stuck a fork in the 35-year reign of American jazz was rock ‘n’ roll’s emergence in the 1950s. Jazz-influenced popular music now had a bratty little brother who couldn’t be muzzled and made just as much of a holler as it emerged on the scene. And just like jazz, rock ‘n’ roll was instantly mesmerizing as an art form to the rest of the world. After rock’s new sound fully emerged mid-century, jazz would never again be the world’s most dominant and popular musical idiom.

While it may be fair to say that jazz was knocked off its pedestal by the new kid on the block, was rock ‘n’ roll something completely out of the blue? Did these two musical juggernauts have nothing in common other than that they became immensely popular in their respective eras? Not if you consider the human throughline that was Louis Jordan, a guy who straddled both the swing era and rock’s earliest beginnings, along with Louis Prima.

Louis Jordan was a musician who, at the beginning of his career, played with the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, and Dizzy Gillespie during the height of swing jazz, only to walk away from it all to start his own thing and help usher in a whole new sound and approach to popular music.

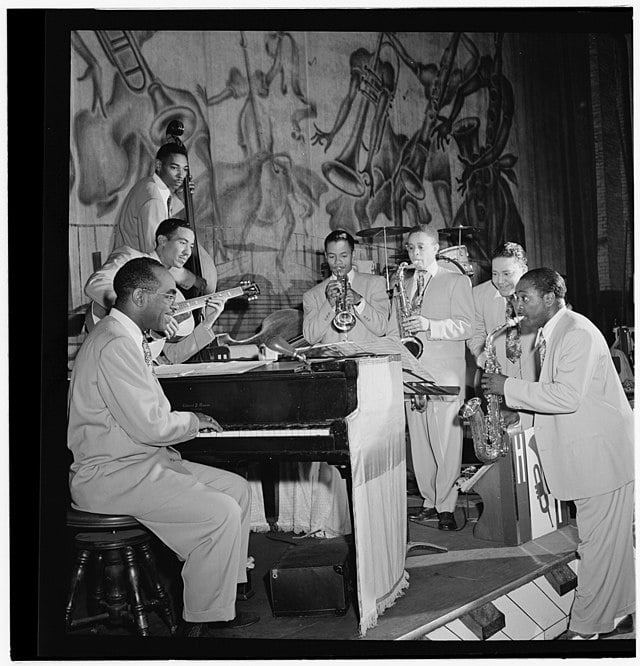

In the late 1930s, we find the young Jordan performing saxophone in several big bands, playing with the best of them, but ultimately deciding to quit these well-paying gigs and form a smaller group to compete with the famous jazz orchestras. This was at the outbreak of World War II when the sound of swing still firmly ruled the airwaves. His unorthodox move would set the stage for what would eventually become rock ‘n’ roll.

Much can be learned about the transition from jazz to rock as dominant musical forces by exploring Louis Jordan’s musical machinations. Let’s start with his sound: Jordan put all the music he’d grown up with into a blender to make his mark in music. If jazz began as a mash-up of traditional European-influenced American music and the African rhythms of its black population, then rock ‘n’ roll’s earliest beginnings were an even more serious mess. In crafting his unique early sound, Jordan pulled from blues, jazz, boogie-woogie, gospel, and every sub-genre a person with a pulse could party to, and he put that new sound front and center with his new band named the Timpany Five. It would ultimately become known as Rhythm & Blues or “R&B” for short, and Jordan’s contribution was trailblazing at its finest.

Jordan didn’t want to front yet another big band. Instead, he pared the sizeable performing ensemble of 20-plus musicians to just five of the hottest players he could find. He focused firmly on the rhythm section featuring a beat described as heavy and insistent. It was like he took a big band equivalent of a B-52 bomber and stripped it down to a street racer that would tear up the tracks every Saturday night.

Jordan’s innovations didn’t stop there. Eventually, he made one of those players an electric guitarist, playing a somewhat distorted guitar. That was in 1946 when he added Carl Hogan, a few years before guitarist Muddy Waters started having hits in Chicago with electrified urban blues. This was a significant shift in instrumentation – from sax and trumpet out front to sax and guitar – and laid the groundwork for the lineup that still exists today in rock.

Jordan’s release of Ain’t That Just Like a Woman was number one on the American R&B charts for two weeks in 1946. Carl Hogan’s guitar intro on that number was not lost on Chuck Berry, who was 20 years old and unknown at the time. He borrowed it to introduce his 1958 hit “Johnny B. Good” and further to solidify rock as the new iconic American sound. Still unsatisfied, Jordan eventually added an electric Hammond organ to round out the sound of a small group of performers. Maybe he was missing something he recalled from the churches he grew up in because, until then, that’s where electric organs were found, not in a jazz band. His lean and powerful sound not only launched the new R&B genre but, in his case, was given the handle of “jump blues”, aptly named since you couldn’t stand to be in the same room with this new sound and not want to jump out of your seat and onto the dance floor.

OK, so let’s take an inventory of Jordan’s unique formula for success: an infectious, basic backbeat for rhythm (check), blues-based songs with repeated riffs in a chorus-based form (check), upbeat lyrics, and a charismatic vocalist in the lead (check). That’s a souped-up recipe for a new hard-driving musical beast. No wonder he’s not only called the father of R&B but the granddaddy of rock ‘n’ roll.

But what drove Jordan in this direction? Was he a visionary who saw the demise of the big bands before anyone else? Perhaps. But Jordan was probably just being practical. For the most part, with big bands, the focus was on the group and not the individual. That approach wasn’t working for Louis Jordan, who loved being the center of attention. Also, big band leaders were inherently conservative, not wanting to upset a successful formula that paid the bills for a large touring entourage. A pared-down group with Louis at the helm allowed him to call his shots and experiment with whatever new sounds he desired.

This was one of the reasons folks like Dizzy Gillespie eventually jumped the swing ship to pursue new bebop horizons, though it took him a few more years to figure things out. Once bebop fully emerged, Louis steered clear of that as well, rejecting its exclusivity and the aloof nature of music most folks couldn’t keep up with. “Jazzmen were playing mostly for themselves,” Jordan remarked at the time, “I wanna play for the people, not just hepcats.” So, he started his scene where he not only trimmed the personnel but planted himself firmly at center stage. He helped launch a new musical era where a single charismatic frontman, singing and playing the lead, with the backing of a tight small ensemble, was the name of the game, and it stayed that way for a long time thereafter.

While rock ‘n’ roll eventually replaced jazz on the marque of American popular music, this wasn’t an abrupt shift in taste. The powerful influences of what African descendants brought to the rest of the American music scene are better understood as an evolving continuum: a river of black-influenced music coursing through the country’s cultural history, starting with African dance to blues, ragtime, jazz, swing, boogie-woogie, gospel, R&B, soul, and then on to rock, funk, rap, hip hop and beyond.

There’s no better example of this river than in the career and evolution of Louis Jordan’s sound. The way he moved through his musical life, picking up whatever ingredients he could add to the pot and make it boil, always hungry for a sound that was just familiar enough and, at the same time, just new enough to hit the right chord with people of every color in America. And man, did he hit it. During the three-plus decades of his career, he was one of the most successful African American recording acts, crossing over repeatedly from the so-called ‘race’ charts to the whiter American top 40. He significantly influenced Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and nearly all the guys who eventually launched rock to global attention in the mid-1950s.

So, rock music didn’t come out of nowhere to topple jazz: they were all part of the same powerful influences pounding on America’s musical doors and demanding to join the party. For a while, Louis Jordan was definitely knockin’ the loudest.