When the announcement landed on Twitter on 21 November 2022 that Wilko Johnson had died, it elicited an outpouring of responses from friends, fans, and fellow musicians—particularly guitarists. Though for some, Johnson would always be in the footnotes in the history of 1970s British rock, for others, his band Dr. Feelgood and the pub rock genre both were associated with represented canaries in the coal mine, providing preview warnings of punk and post-punk upheavals ahead.

Despite only participating as guitarist and songwriter on Dr. Feelgood’s first four albums, Johnson’s work on Down by the Jetty (1975), Malpractice (1975), Stupidity (1976), and Sneakin’ Suspicion (1977) established him as a unique guitarist with a sound and intensity distinct amongst his pub peers.

When Stupidity hit the top of the British album charts during punk’s breakout year, 1976, it was apparent that a new spirit was in the air, and it was out of step with the pop gloss of glam and the complexity of prog that then ruled Britannia’s rock waves. Instead, the Dr. Feelgoods stripped rock and R&B down to its bare bones, leaving only a skeletal sound that time and technology had seemingly bypassed. In that subtraction, the band added speed and unadorned rawness. Cutting through their tight, barren rhythm section was Wilko’s Fender Telecaster, emitting elemental blues-based patterns via a simple tube amp. Nothing could have sounded further from the rock “god” theatrics of contemporaries like Eric Clapton, David Gilmour, and Brian May. A new generation of guitar heretics and anti-heroes was paying attention.

Jagged and frenetic, Johnson’s style emerged from listening to Mick Green of the late ‘50s/early ‘60s British combo Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. Green’s playing showed the young aspirant how one guitarist could sound like two by integrating brief solo licks into the gaps of staccato rhythm playing. In homage, Dr. Feelgood took their name from a song the Pirates had covered and included a cover of Green’s “Oyeh!” on their debut Jetty album.

“I tried and tried to copy Mick Green. But I’ve got my own way of doing it,” Wilko later reflected (“Wilko”). His “own way” involved an acceleration of speed, no doubt driven by the copious amounts of amphetamines he ingested during the ‘70s. It was the resulting intensity, rather than the blues riffs themselves that subsequent punk players were drawn to.

Life in the years before Dr. Feelgood offered few signs that Johnson would become a godfather of punk. After pursuing an interest in Anglo-Saxon literature at Newcastle University, he satisfied a standard hippy yearning by travelling extensively around India. On returning to England, he commenced a teaching career, settling back into his childhood home of Canvey Island.

Situated on the River Thames estuary 15 miles west of Southend, Essex, Canvey Island is known for its creeks, mudflats, and petrochemical plants. It is also recognized as a hub of early ‘70s pub rock, boasting key venues like The Lobster Smack Inn, The Monico Nightclub, The Canvey Club, and, across the water in Southend, The Railway Hotel. Alongside Dr. Feelgood, the region was also home to Mickey Jupp, the Kursaal Flyers, and Eddie and the Hot Rods, all pivotal acts in the incipient scene.

Seen through a romanticist’s eyes, as it is by director Julien Temple in Oil City Confidential (2009) and The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson (2015) music documentaries, Canvey Island can be imagined as a London equivalent to the Mississippi delta, its jetties and beat-up boats providing the source material to create an alternative British bayou blues. Wilko and his neighbors, Lee Brilleaux (vocals), John B. Sparks (bass), and John Martin (drums), no doubt fantasized as such when they formed Dr. Feelgood (out of the Pigboy Charlie Band) in 1971. Indeed, the title of their debut album, Down by the Jetty, helped feed the kind of psychogeographical significance Temple emphasizes. His films frame Wilko as punk before punk, dredging up a faded history by putting both the guitarist and Canvey Island back on the map as key participants in forming punk aesthetics.

The roots rock, country, and R&B played in the pubs of Essex and London during the first half of the ‘70s did not foreshadow punk rock so much as its attitude and infrastructure. Pub rock’s emphasis on live performances in small cramped venues signaled the importance of audience interaction and presenting music with energy and passion. Even when its bands did release albums, they spent little time producing or editing them, often preferring just to put out live recordings, as Dr. Feelgood did with Stupidity. Knob-twiddling and technical effects were regarded as the extravagances of prog, glam, and classic rockers, not of pubbers, who were more inspired to emulate the uncooked immediacy of Howlin’ Wolf or early the Who. Making an implicit statement of opposition to the sophisticated music of their time, Dr. Feelgood chose to record their debut album live in the studio, with few overdubs, and in ol’ time mono.

As addressed in the BBC’s “Pre-Punk: 1972-76” episode of their Punk Britannia series (2012-), pub rock’s existence also challenges the long-held assumption (by some) that British punk developed solely from its bands hearing those that frequented New York’s CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City clubs. As much as the influence of the Ramones et al. is undeniable, even those upstarts were enamored with London pub rock.

Blondie’s Chris Stein recalled an all-night party he hosted in his Bowery loft in 1975. In the wee hours, drummer Clem Burke showed up clutching a copy of Dr. Feelgood’s Malpractice album that he had just picked up in England. Stein proceeded to play the album repeatedly, noting, “Everyone was transfixed. It was so simple and raw. I remember people saying, ‘This is what the Ramones are going to sound like when they make a record'” (Williams). Of course, 1976’s The Ramones sounded nothing like Malpractice regarding genre; but in relation to capturing a stripped-down elemental sound that exuded aggression and intensity, it was a natural successor.

Indeed, Johnny Ramone and Wilko Johnson offer the two main—if divergent—roads into punk and post-punk guitar playing. Whereas the Ramonic style involves repetitious downward strums on the bass strings of barre chords, the Wilko technique uses polyrhythmic down-and-up chops on open chords, the bass E string occasionally muted by the thumb to create a scratching sound as the high notes cut through on the “stabs” upwards. Brian James (the Damned), Joe Strummer (the Clash), and Pete Stride (the Lurkers) adopted Johnny Ramone’s approach, while Paul Weller (the Jam), Hugh Cornwell (the Stranglers), and Jon King (Gang of Four) adapted Wilko’s.

The Wilko disciples differed from the Johnny Ramone-inspired in other ways, too. Whereas the Ramonic template relied on distortion, fuzz, or overdrive to create a wall of noise, Wilko’s was a clean, effect-less sound with the treble turned high to highlight each note across the fretboard. One can hear a comparable sound in those US contemporaries Stein alluded to, particularly in Richard Lloyd and Tom Verlaine from Television and Robert Quine from Richard Hell and the Voidoids. You can hear it in early Jam songs, too, like their debut single “In the City” (1977), where Paul Weller draws jagged ferocity from his Rickenbacker. Weller often paid tribute to Wilko, calling him his “first ‘70s guitar hero” and adding, “I can hear Wilko in a lot of places. It’s some legacy” (Taysom). The ubiquity of his choppy style was also due to its malleability, as amenable to the folk-punk of Billy Bragg as the funk-punk of Jon King.

Wilko and Dr. Feelgood were always as much apart from as a part of the pub rock movement, and they distinguished themselves from the pack on criteria beyond just music. Populated by bearded men wearing flared denim trousers, drab dress shirts, and kipper ties, the pub scene certainly made a “fashion” statement against the peacocks of glitter rock; however, its dowdy threads would never be countenanced by the likes of Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood, nor by the broader punk subculture.

Dr. Feelgood, nevertheless, made some sartorial gestures at odds with pub standards. Yes, Lee Brilleaux wore a lapelled suit jacket onstage, but it was always notably filthy and sweat-drenched, making him look like a gangster fleeing from Regan and Carter in an episode of the ’70s detective series, The Sweeney. Wilko was much more visually striking, his all-black outfits blending with his black Stratocaster, while his clean shave and short hair signified a break from the still lingering hippy era. “The way we looked…nobody else was like us at the time,” he recalled (Cartwright).

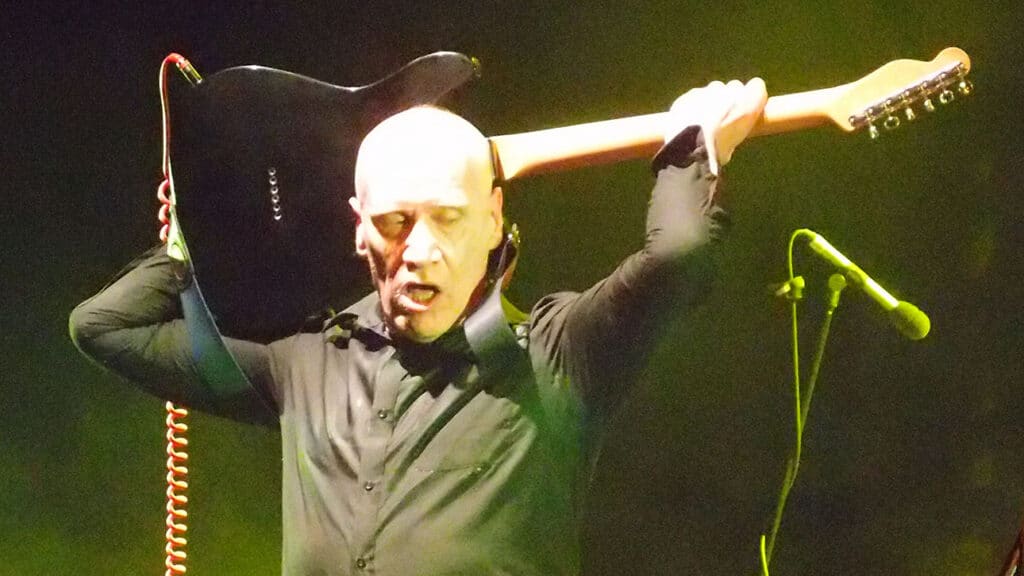

Wilko’s sharp and sinister look extended to his performance craft as well, where his jerky cross-stage dashes—guitar held high and pointed outwards like a machine gun—seemed like a punk parody of Chuck Berry’s duck walk. Underscoring the choppy nature of the guitar rhythms, he, says Garth Cartwright, “carved up the stage like a man possessed”, restrained solely by the reach of his curly red guitar cable. Such manic manoeuvers caught the eye of Jon King, who incorporated similar ones onstage to match the angular grooves of the Gang of Four.

Adding to his overall persona as an unhinged presence to be reckoned with, Wilko’s characteristic crazed stare established another performative precursor to punk. Johnny Rotten claimed he had acquired his murderous glare from watching Laurence Olivier play Richard III (Lydon, p.17), but one suspects that the source of inspiration may have come from closer to his scene. The producers of Game of Thrones certainly appreciated the unsettling effects of Wilko’s demeanor, casting him as Ser Ilyn Payne, a mute executioner reliant solely on looking daggers to intimidate.

A year after that acting gig, Wilko was diagnosed with terminal cancer before being given a reprieve after further evaluation and a major operation. He went on to have a fruitful final eight years, Temple’s documentaries facilitating a revival of interest in an artist whose star had long been waning. Audiences grew for his shows, too, thanks to the surprise success of Going Back Home (2014), an album he recorded with Roger Daltrey following the cancer prognosis. At the time, Daltrey observed of his friend, “He’s one of those British guitarists that only the Brits make” (Sweeting), perhaps suggesting that what the likes of Johnson do best is bring an imprint of personality, attitude, and interpretation to music, rather than slavishly copying preexisting forms. Former Clash and Public Image Limited guitarist, Keith Levene, concurs, characterizing him as “a nutter who knew what he could play and knew what he liked and didn’t need to pretend anything” (Johnson, p.186).

Others have weighed in with their tributes since death finally caught up with Johnson in November. He “carved legend from life“, said Alex Kapranos of Franz Ferdinand; “he inspired a generation of twitchy dorks like me”, tweeted Steve Albini; he is “one of my all-time Tele heroes“, added Blur’s Graham Coxon. A guitarist’s guitarist (though rarely featuring in critics’ “Best of” lists), a cursory survey of rock history since 1975 reveals evidence of Wilko’s style, rhythms, and approach cropping up wherever choppy guitar-based music has been played and performed. As Paul Weller opined, “It’s some legacy.”

Works Cited

Cartwright, Garth, “Essex machines; Julien Temple’s new rockumentary explores the protopunk genius that was Dr Feelgood”. Sunday Times. 17 January 2010.

Johnson, Wilko, with Zoë Howe. Looking Back at Me. Cadiz Music Limited. 2012.

Lydon, John. Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs. Picador. 1994.

Sweeting, Adam. “Wilko Johnson obituary“. The Guardian. 23 November 2022.

Taysom, Joe. “How Wilko Johnson inspired Paul Weller and The Jam”. Far Out. 28 November 2022.

“Wilko Johnson Demonstrates His Guitar Technique, 9.7.12.” Youtube, uploaded by punkrocksal. 10 July 2012.

Williams, Alex. “Wilko Johnson, Scorching Guitarist and Punk Pioneer, Dies at 75”. The New York Times. 30 November 2022