The 2022 Oscars were a ground-breaking affair for the Latinx community. In many ways, the annual event was one for the history books. While Ariana DeBose was only the second Latina to win an Oscar for her supporting role in Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story (2021), Disney’s Colombian-themed Encanto (2021) won the award for Best Animated Film. Seasoned Spanish actor Javier Bardem was nominated as best actor for his role in Being the Ricardos (2021), and celebrated Mexican director Guillermo Del Toro garnered four nominations with his Nightmare Alley (2021). Thus, while the debate surrounding the underrepresentation of the Latinx community in the media is profoundly necessary, Latinx identities have become more noticeable in film—especially animated films. For example, Guillermo del Toro’s The Book of Life (2014), and Disney’s Coco (2017) debuted to rave reviews. In 2021 a cavalcade of Latinx actors (Zoe Saldaña, Gael García Bernal, Rita Moreno, etc.) lent their voices to Maya y los tres, an animated television mini-series directed by Jorge Gutiérrez.

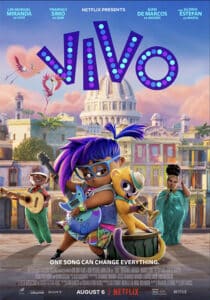

But what has the Latinx community gained in film and media representation? What work remains to be done? The 2022 Oscars spotlighted the Latinx community, but greater representation does not necessarily imply deeper conversations. The 2022 Oscars may have missed a prizeworthy opportunity for more culturally significant discussions about fundamental issues affecting the Latinx community: immigration and diasporic identities. This missed chance is due, at least in part, to the exclusion from the awards of another 2021 animated film: Kirk DeMicco and Brandon Jeffords’ Cuban-themed Vivo.

Originally scheduled for a theatrical release in July 2021, Vivo debuted on Netflix that August. The computer-animated musical, whose titular hero is voiced by singer-composer Lin-Manuel Miranda, comes after Miranda’s other successes—the musicals Hamilton (2015) and In the Heights (2021), and the animated film Encanto (2021). The multitalented Miranda wrote all of the 11 songs for Vivo, most of which follow the musical template that has been so successful for the composer: melodies that meld hip-hop rhythms with Latin flourishes.

Not only has Vivo garnered less attention than other Latinx-themed animated films, but reviews of the film have also been less than favorable. The New York Times signals the production’s “odd turns and clichés”, while The Guardian characterizes Vivo as a “patchwork of better kids’ films”. I lament that these lukewarm reviews miss Vivo’s subtle engagement with cultural and political issues crucial to the Latinx community, making for a compelling film when noticed. Specifically, Vivo successfully expresses what some have referred to as a “Trump-era anxiety” surrounding transnational migration and the complexities of diasporic identity.

Vivo opens in Havana, where the elderly Andrés Hernández and his pet kinkajou, Vivo, busk daily in the city’s iconic Plaza Vieja. The duo’s act is beautifully backdropped by Havana’s decaying architecture: El Capitolio, the Malecón, and the Cayo Hueso neighborhood. Foreign tourists snap photos while the musical duet performs “One of a Kind”, a song in which Vivo (voiced by Miranda) cajoles onlookers to “drop their dollars and pesos” even if “attendance is low.” The hope to leave Cuba’s genteel poverty behind becomes a real possibility when an old flame — famed singer Marta Sandoval — invites Andrés to perform with her at her farewell concert in Miami.

Marta, voiced by Gloria Estefan, seems inspired by Celia Cruz, one of Cuba’s most famed singers. Like the fictional Marta, Cruz abandoned the idea of returning to the island early in her career. Montage flashbacks of Andrés and Marta’s salad days in Cuba are drawn in hot, vibrant colors, and Googie shapes so characteristically of the late 1950s. Vivo, too, imagines the island’s pre-Revolutionary times in terms of economic and cultural splendor. Andrés gets swept up in the idea of reconnecting with Marta, referring to the opportunity as “the greatest gift in the world. A second chance!”

Vivo, in turn, meets the plan with trepidation. Storming off in a huff, the kinkajou spends the night in the street. In this way, the film ingeniously depicts the dilemma that many Cubans—indeed, migrants of any nation, face: To stay or go? How to remember the past? How to think about lost opportunities? What Vivo gets right is its ability to depict the key emotions of diasporic communities; specifically, the film points to the feeling many migrants experience, which can most cogently be understood as “ambiguous loss”.

Similar terms have been employed to describe the migrant journey, and Coco, too, encourages lessons on grief. The term “ambiguous loss” comes from Pauline Boss’s groundbreaking 1999 study of the same name, Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Therein, Boss defines the feelings of uncertainty when loved ones are lost due to mental illness, immigration, Alzheimer’s— or deaths or disappearances that remain unresolved. Boss, a psychologist, argues that uncertain losses are more likely to result in exhaustion, depression, and anxiety; and those who struggle with puzzling absences often rescind emotional support.

Vivo is replete with incidents of ambiguous loss. The day after Marta’s invitation arrives, Vivo returns home to find Andrés has passed away during the night, his hand still clutching the song he composed for Marta so many years ago. To mitigate his feelings of loss, the singing kinkajou tasks himself with personally delivering the song to Marta. The following night, we meet Rosa Hernández (voiced by Zoe Saldana), whose late husband was Andrés’ nephew and who has also flown from the Florida Keys for Andrés’ funeral. Gabi (voiced by Ynairaly Simo), Rosa’s hip-hop-loving, empathetic but rebellious daughter, accompanies her mother.

Effectively, the scene is defined by unresolved losses: deceased husbands and fathers, unresolved arguments, and trips not taken. Gabi and Vivo exchange words at the funeral before the latter hides in Gabi’s suitcase to reach Miami and deliver Andrés’ composition to Marta. Although Vivo never strays far from the lighthearted tone of a children’s animated film, it’s difficult not to understand the kinkajou’s journey as mimicking that of many Cubans migrants who risk their lives traversing open seas in hopes of reaching the United States. Like so much of Cuba’s diasporic community, Vivo is a tale of two cities: Havana and Miami.

After the kinkajou’s stowaway trip, Vivo emerges from Gabi’s suitcase, both humorously and poignantly, staring straight into an aquarium empty of fish in Gabi’s room. The tank is populated with tombstones dedicated to the memory of the girl’s former pet fishes: “Spike”, “Enzo”. and “Dupree”. We cannot help but wonder: Will Vivo face a similarly deadly fate at the bottom of the ocean? Vivo and Gabi decide to make the trip from Key West to Miami to deliver Andrés’ final musical message before Marta’s imminent performance. Again, although Vivo stays well within the traditional parameters of an animated film, during their trek, Gabi and Vivo experience a fear of persecution not unlike that felt by immigrants—whether documented or not.

Their journey begins on a bus whose driver refuses the kinkajou a ride: “No pets, no critters—whatever you are, get off of my bus! Not on my watch!” After the brusque rebuff of Vivo, passengers on the bus cheer the driver’s decision, to which he replies, “Oh, you like that? I came up with that myself!” Of course, those of us who are at least as old as Lin-Manuel Miranda remember that “Not on my watch” is not a truly novel turn of phrase. No one less than President George W. Bush used the construction on various occasions during his reelection campaign whistle-stops in 2004.

Vivo and Gabi decide on the shortest route between Key West and Miami—on a makeshift raft through the Everglades. During their swampy journey, Vivo and Gabi are trailed by the Sand Dollars, a group of three girl scouts who hound the two runaway protagonists with an authoritarian and hypocritically annoying strain of “wokeness”, ignorant to the oftentimes traumatic stakes of immigration. The scout troop’s good-natured concerns about Vivo’s well-being approach xenophobic inflexibility. As they snarkily explain, a kinkajou is not “native to these parts” and thus “cannot survive in this environment”. The scouts follow Gabi and Vivo through the dangerous wetlands of south Florida, demanding that they produce the kinkajou’s “vaccination certificate” since his “eyes look a little cloudy” and his “coat is kind of mangy”.

The film concludes when Vivo and Gabi deliver Andrés’ song to Marta, thereby allowing the famed singer the opportunity to reencounter her past, reanimate her memory, and alleviate her sense of ambiguous loss. Vivo and Gabi, in turn, re-cathect their respective emotions—the loss of her father and the death of his master, Andrés—by taking their song and dance act to Key West’s Mallory Square. With Vivo’s Latin melodies and Gabi’s hip-hip swagger, our dual protagonists symbolically figure a type of international reconciliation. Together, they epitomize a diasporic identity constituted by a confluence of cultures.

And yet, I would be remiss if I failed to mention that Vivo’s happy ending is the stuff of fairy tales. After all, with the end of the so-called “wet foot, dry foot policy” under President Obama, no matter how cute of a kinkajou Vivo is, as a foreigner, he would not be allowed to stay in the United States. Vivo deserves a careful viewing, as it constitutes a subtle exploration of immigrant issues and diasporic identities. Like the United States’ immigration policy, Vivo, too, sidesteps more lasting, more poignant resolutions to what are ultimately life-and-death issues for so many in the Latinx community.