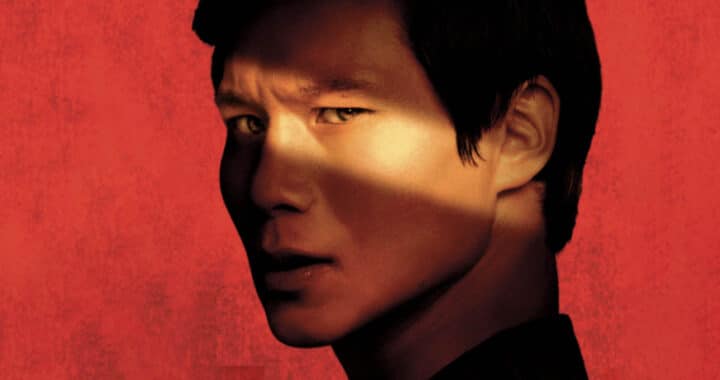

‘The Sympathizer’ Fractures Identity into a Knockout Kaleidoscopic Tale

The mini-series adaptation of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s kaleidoscopic tale The Sympathizer is a knockout account of colonialism, war, and (the loss of) identity.

The mini-series adaptation of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s kaleidoscopic tale The Sympathizer is a knockout account of colonialism, war, and (the loss of) identity.

Film-goers viewed One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest as a metaphor for ’70s era struggles against war, racism, and political corruption.

While the original Star Wars trilogy display George Lucas’ youthful optimism, the prequels reveal his dismay and regret at the world created by the Boomer generation.

As cool as Marlon Brando, James Dean, Jack Kerouac or Dalton Trumbo, rebel Max "Flaco" Greenbaum grows up in Watts Riots-Vietnam-draft-era L.A. Too smart (and smart-mouthed) for school, the violence of this world is drawn in deep and lingers like the long, slow, life-saving drag of a cigarette.

As with Da 5 Bloods, Spike Lee's films are replete with experimental aesthetics that deconstruct the conventions of (white) Hollywood and re-frame and re-contextualize Black lives and Black history.

Spike Lee's Da 5 Bloods engages with the notion of perpetual conflict. But how well does it fit into the current social milieu of demonstrations against police violence?

Despite Mailer's literary merit, his persistent fetishizing of the black body in his writing during the '60s gets tiresome. Yet we can't ignore these works.

Historian Kathleen Belew painstakingly details the influence of the Vietnam wartime experience on the evolution of white power ideology.

Apocalypse Now is the most iconic American film about America’s War in Vietnam. But we are not here to expand the myth. We are here to explode it.

This book offers a poignant and jarring reminder not just of the resilience of the human spirit, but also of its ability to seek solace in the materiality of one's present.

God and the Devil are intertwined again and again in the character of Randle McMurphy (Jack Nicholson); he’s just as capable of taking these men to Hell as to Heaven.

Steve Pick: Ken Kesey wrote one novel of great note before becoming the poster boy for acid use as the star of Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was made into a play almost as soon as it was published in the early ’60s, but the film adaptation didn’t show up until 1975, smack dab in the middle of the only decade that could have captured the mixture of oppression, comedy, violence, and horror. So, what do you say, Steve? Let’s talk about form, let’s talk about content, let’s talk about interrelationships, let’s talk about God, the devil, Hell, Heaven. Are you on the bus or off the bus with this one?

Steve Leftridge: Well, Steve, I’ve always been crazy; it’s kept me from going insane. Of course, I would hope to be on the bus with McMurphy, headed for the fishing boat, or out bird-dogging in a convertible, where Billy ought to be. As opposed to the alternative, which is stuck in a forced routine, medicated into numbness, and conscripted into therapy sessions that pry into my most painful and private memories. McMurphy obviously prescribes the former and not the latter. Do you think he’s a heroic character in this sense?

Pick: Well, I’m not sure how heroic a 38-year-old man imprisoned for having sex with a 15-year-old girl can be, and I’m certainly not sure that his actions were always responsible, no matter how they turned out. Of course, everything turned out for the best on that fishing boat, but that was as much a matter of luck as it was a function of freedom. The “therapy” of the early ’60s was clearly horrific, but McMurphy’s unbridled id isn’t all that appealing, either.

It is clear that unlike the evil Nurse Ratched or the merely disconnected Dr. Spivey, McMurphy does genuinely care about the various inmates in the ward as individual people who have wants and desires and needs. Ratched’s attempt to force each patient into a conformist box does nothing but hold them in place, or worse, as ultimately we are shown when Billy winds up dead. She stands in opposition to anything that could possibly produce a moment of pleasure. McMurphy, on the other hand, acts to please himself, but in the process, makes his fellows feel alive.

Leftridge: Yeah, I think McMurphy would be a real pain in the ass to have around in most situations and would kick against authority figures of any kind in ways varyingly understandable and ridiculous. However, in this case, with the other patients, he’s generally a force for good. If nothing else, McMurphy challenges the very notion that these other guys are nuts: “What do you think you are, for Chrissake, crazy or something? Well, you’re not! You’re not! You’re no crazier than the average asshole out walking around on the streets and that’s it.” That’s a refreshing message that the patients certainly aren’t hearing from anyone else, least of all Nurse Ratched, who is doing everything in her power to instill the opposite. When McMurphy takes them fishing, there’s that telling moment when he introduces them all to the guy at the dock who tries to stop them as doctors — “Dr. Martini, Dr. Harding, famous Dr. Scanlon” — and each man assumes a look of great dignity and importance, not seeming crazy at all because they’re given a chance to feel a semblance of confidence. These characters’ problems are so obviously symptomatic of the way they’re being handled, and perhaps the clearest example is Billy, whose stutter gets better when McMurphy makes him feel normal about his very normal desire to be a sexual person. You mentioned McMurphy as a sexual criminal; how do you suppose this plot point is related to Billy’s hangups?

Pick: Billy’s hangups aren’t only sexual; he has serious mother issues, as well. But McMurphy projects his own sexual interests on to others. When he explains to Dr. Spivey that no man could resist “that red beaver”, he is resisting taking credit for his crime. When Billy says he’s interested in Candy, McMurphy puts his own spin on the problem. A boy who can’t even bring himself to talk to women needs more than a tumble in bed, but that’s what McMurphy gets for him. Candy isn’t interested in Billy, but, as McMurphy says, “He’s cute enough, right?” Don’t get me wrong, Ratched’s completely responsible for demolishing Billy the next morning, shaming him with thoughts of what his mother will think when she finds out her son is a sexual being. But McMurphy’s set the whole thing up. Billy wasn’t stuttering in the morning, but he was going to go right back to it anyway, once he discovered sex and love weren’t the same thing.

I think Miloš Forman (and Ken Kesey, for that matter, though it’s been 30-something years since I read the novel) sees McMurphy as a positive force in the lives of these men, and it’s clear he brings them to experience things in a better and richer way. But, unfortunately, they were more troubled than the average asshole on the street, and ultimately, McMurphy’s therapy is just as dangerous as Ratched’s. I watched that whole fishing boat sequence through my fingers, convinced something terrible was going to happen at any moment, especially when nobody was at the helm. That’s why I quoted Harding earlier: to me, God and the Devil are intertwined again and again in the character of McMurphy; he’s just as capable of taking these men to Hell as to Heaven.

Leftridge: I find that our positions are diverging more here. Regardless of authorial intent — and I agree with you that Forman and Kesey see McMurphy as the good guy — I don’t think McMurphy straddles the line as closely as you do. Yes, McMurphy coordinates the romp between Billy and Candy, but that’s a crime only as bad as his inability to foresee the extent to which Nurse Rathed would emotionally terrorize Billy for doing it. It seems to me that McMurphy is only facilitating what these characters already want or need.

Billy wants to screw Candy. When all the other men are gathered around McMurphy on the boat, learning to bait hooks, Billy is over hitting on Candy. It’s what his body is telling him to do, and the forced repression of these natural desires has turned him into a stuttering anxiety-filled “cuckoo”. McMurphy is obviously an unapologetically hypersexual dude — the statutory rape, the nudie deck of cards, his own tryst with Candy, etc. — which is one of the reasons Nurse Ratched so despises him. She shames Billy about sex throughout the film: during one of her therapy interrogations, she’s careful to connect Billy’s first suicide attempt to the time he proposed to his girlfriend. I’m not saying that these men don’t have problems; Billy’s mother has no doubt driven him into a terrible corner, but I think McMurphy is an overall healthy antidote to the other medicine they’ve been receiving. If nothing else, he gives them the confidence to at least vote against Nurse Ratched’s desire to keep the from watching the World Series, something they wouldn’t have dared do before. And he empowers Chief to fly over the nest altogether.

Pick: Ah, you bring up Chief, who is one of the most fascinating characters in the whole film. He’s the narrator of the novel, but he seems, for a long time, to be less important in the film. Still, Will Sampson does a wonderful job bringing him to life in every scene. I could watch that basketball game a hundred times in a row, I think. Since Chief is pretending to be deaf and dumb, McMurphy has to work hard to make the towering man into an effective player, but it’s so rich to watch him stand under the basket and simply place the ball into the net, then walk very slowly and carefully to the other end only to reach up and keep the ball from falling through the net. And, of course, the scene wherein McMurphy gets him to raise his hand in support of watching the World Series is priceless as well.

Because he has so little dialogue in the film, and because my memory of the novel is vague, Chief’s motivations are somewhat mysterious. In the book, it was explained that he had become depressed watching the US humiliate his father, and had been on the ward for many years. And, yes, McMurphy does help him to realize the world outside may be worth investigating again. It’s heartbreaking to watch the scene wherein Chief tells McMurphy he really can’t leave, though once the action is brought into play, it seems he’s ready to go. I’m not sure why he and McMurphy fall asleep when their chance to leave comes up – is it a case of them simply being less courageous than they seem? At any rate, once McMurphy receives the worst punishment imaginable for his rebellion, a lobotomy, Chief does him a solid by suffocating him with a pillow, then removes the water faucet and smashes his way to freedom. He seems likely to have a decent life for himself after the film is over, something I fear the others will not.

Leftridge: Unless they catch up to Chief and shoot him dead or lobotomize him. Don’t tell anyone, but I’ve never read Kesey’s novel, so Chief as the narrator is intriguing. That moment when Chief reveals that he’s been faking it (“Ah… Juicy Fruit”) is a great moment, which I imagine would be lost with his first-person narration, so I might have to finally read it. His deaf-and-dumb act gets him out of those therapy sessions, another way that Chief “flies over” the system. And, yeah, finding out that McMurphy and Chief passed out rather than escaped is a disappointing moment. There’s that peculiar shot of McMurphy lost in thought for several seconds while Billy is in the office with Candy. It’s as though he knows the game is up, but it’s a fine example of how Forman’s style is to hold back and give his actors plenty of room to work. Forman doesn’t make his presence known through any kind of cinematic razzle dazzle here; he sets up the scene and stays out of the way, which lends the film much of its realism.

Although I haven’t read the book, I do remember that some consider it a Christ allegory, and since you’ve talked about McMurphy being equally hellish and heavenly, I wonder if you can speculate on why some would consider this film The Passion of the Cuckoo. Care to take a shot at it?

Pick: Holy moley, you’ve got me thinking now. Well, McMurphy is both an inmate of the ward and a person from outside, sort of the god/man duality thing. He enters into this world to spread a new message of salvation from the sin of going along with Nurse Ratched’s program. He performs at least one miracle, producing a World Series game out of thin air, at least the equivalent of water into wine. He isn’t a fisher of men, but he teaches men how to fish. He associates with prostitutes, and sees the humanity in them. He overturns the temple when he gets into the fight in the ward. I assume we could stretch Harding into some kind of Judas figure, though that doesn’t match up quite as neatly. But there is a Last Supper, the whole crazy drinking binge allowed by Scatman Crothers (and gosh, I hadn’t thought of him in years — what a great actor!) leading up to Billy’s sexual awakening. McMurphy is then tried, leading up to Spivey washing his hands of him via lobotomy. Chief then allows him to give the ultimate sacrifice so that all the sins are forgiven. Yeah, I can see the connections now.

Before I turn it over to you again, I want to point out how terrific every actor is in this film. Nicholson, of course, is in his prime here, and is so good you forget he’s an icon, even though many of the actions he pulls here are among those which made him so imitated. Louise Fletcher is perfect as Nurse Ratched, with an icy control over her emotions, an evil disconnect from her patients, and yet enough grace notes to make us think she really believes her ways to be best (though there is also a clear element of revenge when she says she believes she can help McMurphy). I’ve mentioned Will Sampson and Scatman Crothers, but special notice should be given to the great performance by Sydney Lassick as Cheswick, and two future members of the Taxi TV cast, Danny DeVito as the impishly stubborn Martini and a very young Christopher Lloyd as Taber.

Leftridge: Jesus Christ, you did great work on the New Testament allusion. The whole disciple angle seems fairly clear to me. I would place Billy in the Judas role, though; after all, when Nurse Ratched demanded that Billy name those responsible for initiating the rendezvous with Candy, Billy gave McMurphy up. Also like Judas, Billy later killed himself. Does the fact that McMurphy stays behind rather than escaping equate to a sacrifice? In any case, after McMurphy’s “crucifixion”, the other patients speculate that he’s actually still alive: “McMurphy escaped! He beat up two of the guards!” The patients are also using his language (“It’s ‘buggered’!”), playing poker now instead of Monopoly, suggesting that McMurphy has permanently changed things, even in death, most dramatically in “saving” Chief, who has escaped the hell of the hospital.

I’m glad you mentioned the acting in the film. Everyone is perfect, a credit to the screenplay and Forman’s direction, but it has to be one of the film’s in which I am most reluctant to take my eyes off one particular actor’s performance. Nicholson has so many moments of greatness in this film — the basketball scene, the attempt to lift the water fountain, the World Series improvisation, the electric-shock therapy session. As a result, I don’t think I’ll ever tire of watching this movie. Jack is crazy good.