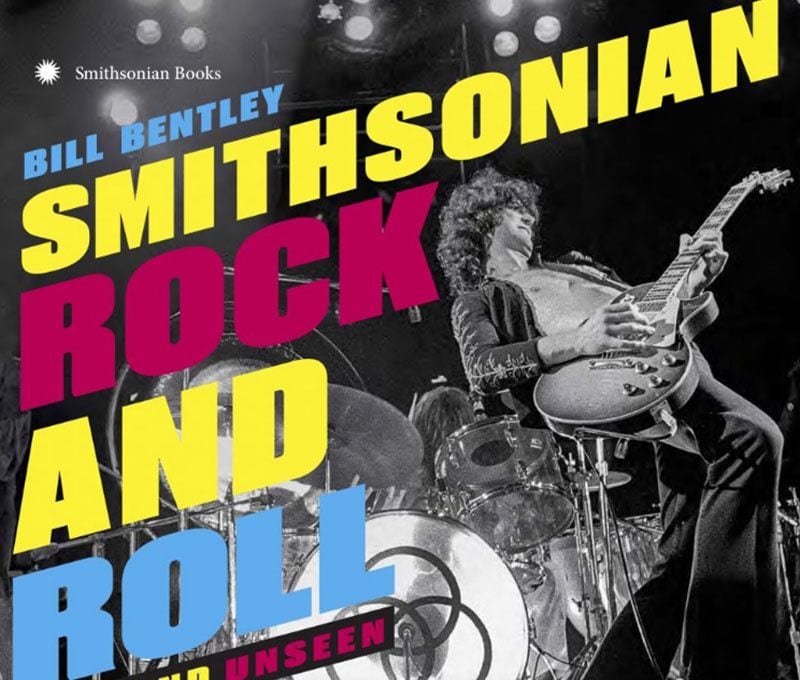

Over a year ago, the Smithsonian held an open casting call of sorts, asking for unpublished concert photos from music fans who just happened to capture an illuminating moment from an iconic onstage performance. Out of thousands of submissions, over 150 were selected and paired with various professionally-taken photographs to create Smithsonian Rock and Roll: Live and Unseen: a type of graphic encyclopedia of popular music from the late-’50s to 2016.

The book invites us to question what it is that makes a concert photo important. Is it the time or circumstance in which it was taken? Is it in the subject and what they were doing at the moment? Do lighting, coloring, and atmosphere turn an ordinary photo into a work of art? Certain shots, such as those of Aretha Franklin at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago (which made headlines for reported police brutality against the anti-war protesters standing outside) or the grainy, partially obscured photograph of Ritchie Valens taken hours before his tragic death in the “day the music died” airplane crash, are here mostly for their historical value.

Others, such an image of CBGB’s intentionally distressed and graffitied men’s bathroom, or Elton John decked out in multicolored sequins and feathers in 1973, are here to exemplify a specific moment in time. But of course, many of these photos are here for their artistic merit, such as an ethereally blue-shaded image of David Bowie rising up onstage, or a color photo of The Ramones that due to concert lighting, only appears to consist of three colors: black, white, and red. The fact that roughly half of these photographs weren’t taken by professionals looking for an artistic or meaningful shot, but by average people who were in the right place at the right time, is impressive. In fact, it makes the reader wonder why so many professionally-taken images appear here at all.

The text is written by former A&R director, music producer, and all-around industry big-wig Bill Bentley. His enthusiasm for his subjects is obvious, as he often comes up with just the right turn of phrase to accurately describe an artist or their impact. (For example, he eulogizes Amy Winehouse with, “She sounded as though she had stabbed herself in the heart every time she took the stage.”) He has a peculiar habit of using celestial and outer space-themed terminology, which works well at some times (such as when he says, “If some cosmic twist of fate dictated only one bluesman per planet, ours would belong to Muddy Waters”), but sticks out like a sore thumb at others (such as when he describes The Crickets’ rhythm guitarist as “thumping out beats across one’s solar plexus”).

Rudimentary information on its artists, including birth/death years, the names of seminal albums or songs, and a general overview of their specific sound and influence are featured, but is in no way comprehensive. (For example, The Beatles’ influences, songwriting partnerships, the 1964 Ed Sullivan Show appearance, and break-up is mentioned, but not their early German gigs, innovative stadium concerts, wildly successful movies, or illustrious solo careers.) All of this is divided into seven differently titled chapters, some of which make more sense than others. Naturally, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, and the Who are included in a chapter entitled, “The British Invasion and Beyond: The Future Is Revealed”, but Al Green, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Bob Marley, ZZTop, and Linda Ronstadt grouped together in a chapter entitled “The Wild Side Moves In: Fasten Seat Belts Now” eludes me. Still, the words aren’t as dry and formulaic as what you would likely find in similar books.

A roblem with Rock and Roll: Live and Unseen, however, lies in its selection of subjects. Many seminal rock bands and artists, such as Bill Haley & His Comets, Queen, the Faces, Jethro Tull, Peter Frampton, Heart, the Cars, and more are missing from its pages, while artists associated with other genres are included sparingly, implying that pop (Madonna, Michael Jackson, and Cyndi Lauper), Motown/soul (Aretha Franklin, Marvin Gaye, Otis Redding, Stevie Wonder, and Al Green), and rap/hip-hop (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, the Beastie Boys, Run-D.M.C., and N.W.A.) can be summed up in just a handful of artists. Other genres, such as country, gospel, and contemporary christian music are virtually excluded, with no predominate artists listed.

Most of the pages concentrate on the ’60s and ’70s, which are vividly well-represented, but to the exclusion of other decades. Is it fair or accurate to sum up the past 15 years of rock music with just Jack White, Amy Winehouse, Adele, and Alabama Shakes? One feels that this book would have been made that much greater if it was a bit bigger, giving more space to more artists. On the bright side, though, many little-known yet highly influential artists, such as the 13th Floor Elevators, Laura Nyro, and MC5 are featured. There’s also an emphasis on performers who might not have had major mainstream success, but still define a specific sound or genre, like Dr. John (synonymous with New Orleans) or Los Lobos (an example of Latin or tejano-infused rock).

In short, Smithsonian Rock and Roll: Live And Unseen is a stylish, interesting, and absorbing, yet slightly incomplete look at the history of popular music.