Conventional wisdom tells us that suicide serves one primary purpose. It’s the complete end of everything for the tortured soul. Suffering stops, catastrophes cancel, debts die. For the unconventional, the artists who choose this way out, suicide also casts a glow over all the work they leave in their wake. Ernest Hemingway takes a shotgun to the head in 1961, and all the macho posturing in between every line of his short stories and novels takes on new meaning. Kurt Cobain does the same, in 1994, and his visual and aural image of grunge and despair is realized. For the conventional and mundane among us, suicide only amplifies the suffering of survivors who are suddenly alone in a world of strangers. For the artist, suicide becomes the primary theme of all their work.

The blueprint for the tragic post WWII female poet was forged in stone by Sylvia Plath, who took her own life on 11 February 1963. In many photos she came off as equal parts innocent and alluring, the hint of a strawberry blonde coquettish flirt hard to disguise under all the processed conformity of the ’50s. She was a Boston born and raised daughter of relative privilege whose father was a Boston University entomologist. He died in 1940, shortly after Sylvia’s 8th birthday, so readers (then and now) of her vicious poem “Daddy” (1960) might wonder about the source from which she drew her angry inspiration. She spent time at McClean’s Hospital, the legendary location for mixed-up children of the emotional twilight zone. She excelled in her time at Smith College. There was a burgeoning and successful writing career, chronic depression, marriage to poet Ted Hughes, and death halfway through her 30th year, at her chosen time and on her chosen terms.

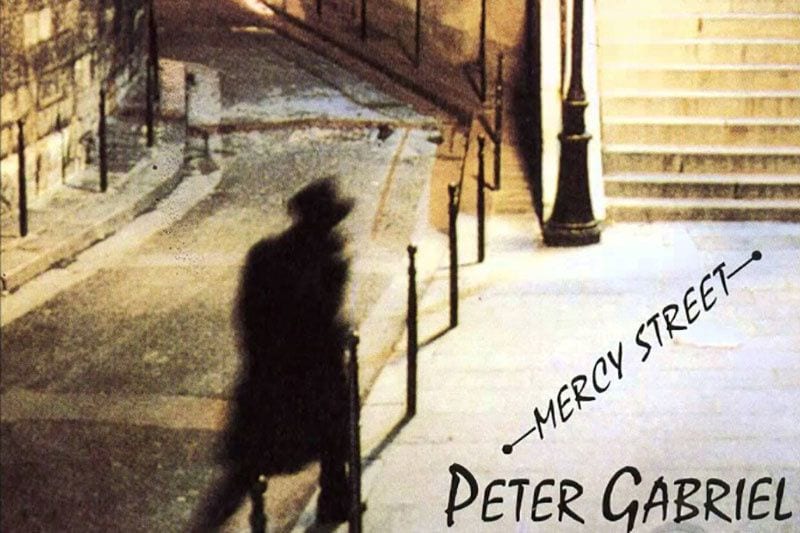

Anne Sexton took up the mantle of tragedy and ran with it. Three years after Plath’s 1963 death, Sexton’s collection Live or Die won the Pulitzer Prize. Her two-act play Mercy Street was produced in 1969. Her first posthumous collection, 45 Mercy Street, published two years after her suicide, continued the themes of searching, longing, wandering into the darkness and surrendering to it because the alternative — dealing and managing — proved impossible. Like Plath, Sexton was Boston-area born and raised. By all apparent proof she was equally defiant and dangerous, comparably talented. Plath was the visual lightness, and Sexton was the moody dark-haired beauty who sometimes modeled, took classes with Robert Lowell at Boston University, and managed to stay tethered to some sort of corporeal identity longer than probably expected.

Consider these lines from 45 Mercy Street, as the speaker seems to realize she’s not going to reach the promise of the address:

“Pull the shades down-/ I don’t care/ Bolt the door, mercy,/ erase the number…”

From The Awful Rowing Toward God:

“I am rowing, I am rowing/ Though the oarlocks stick and are rusty…”

In his lyrics for “Mercy Street”, Peter Gabriel seems to understand that he cannot be so cryptic. He needs to match words with tone (droning or not), and he needs to combine influences. Though named after part of one Sexton poem title, “Mercy Street” also draws energy and imagery from The Awful Rowing Toward God, where the inevitable one-way trip towards the center offers an ending from which there is no escape. “Let’s take the boat out,” he sings. “Wait until darkness comes… Words support like bone.” Secrets are confessed to a priest. There’s a warm after-effect to kissing Mary’s lips. There’s a clever play with words in the chorus. The listener thinks that Mercy Street is where you’re inside out, but instead the line is a command, a verb, an implication that Mercy Street (if you ever get there) will allow you to be your true self:

“Dreaming of Mercy Street/ Wear your inside out/ Dreaming of mercy/ In your daddy’s arms again.”

This is where Sylvia Plath will drift away and stay to herself, quiet between the covers of her novel The Bell Jar or absorbed by Gwyneth Paltrow’s portrayal in the 2003 film Sylvia. Like Virginia Woolf (as seen in Nicole Kidman’s portrayal in the 2002 film The Hours), suicide was the romantic conclusion, the logical end result to a life of personal struggle, of dancing with demons long enough to light the spark that would guarantee literary immortality. For all those women, their work cannot be understood without first confronting the suicides. No matter how many volumes of armchair psychoanalysis and film adaptations have been written about their work, they suffer from a sense of judgement and superiority. We know how suicide biographies end, and determining the clinical source of the sadness only disrespects the work.

Gabriel’s 1986 album So was his fifth solo release since leaving the band Genesis. It was his first non-eponymously titled album, and arguably his most accessible collection of songs. The love song “In Your Eyes” would later be immortalized in the 1989 film Say Anything, and the dance tunes “Big Time” and “Sledgehammer” were perfectly evoked in striking, innovative music videos. “Red Rain” was a politicized plea about global disaster and pending apocalypse, and “Don’t Give Up” (sung with Kate Bush) mixed his depressing verses with her plaintive, hopeful, soaring chorus. Add the experimental songs “This Is the Picture” (Excellent Birds), with Laurie Anderson, and “We Do What We’re Told” (Milgram’s 37), about the infamous 1963 psychological conditioning experiments conducted by social psychologist Stanley Milgram. This was an album that mattered, creating college radio songs with infectious dance beats that more often than not resonated with a moody strangeness.

The most remarkable thing about So is that it managed to hit all targets of mid-’80s era audience demographics and never compromise the artist’s singular vision. Before So, with such solo tracks as 1982’s “Shock the Monkey”, (ostensibly about shock therapy but apparently really a song about jealousy), and 1980’s “Family Snapshot” (definitively about political assassination), Gabriel had never shied away from dark, deep, difficult themes more suitable for pale brooding liberal arts or theater majors. In Mercy Street, side two track two, Gabriel managed to build something haunting and beautiful from an idea so dark and lonely.

Directed by Matt Mahurin and screened only a few times on MTV, this black and white video is worlds away from the splashy fun of “Big Time” and “Sledgehammer”. A man is rowing something out towards a mid-point on a lake. Is it human? Is it cargo? A woman is preparing for her end, carrying out the rituals of her Catholic faith. There’s no apparent connection between these two themes. By video’s end, the man remains on the boat but the identity of the other presence remains unknown. For some, the video, a tribute to Sexton, was “…homage, elegy, pastiche and biography.” Everything is hidden. “The song itself is unpredictable, based on a drone that allows for various materials to be brought in and out of the mix… Mahurin’s imagery and Gabriel’s music share an affinity of tone and affect…” Unlike many of the other big MTV hits at the time, (including Gabriel’s), “Mercy Street” made the viewer work for an end result that remains elusive. None of this is easy because nothing about the subject is convenient or comfortable. Why, then, is it hard to forget?

The simple answer is that sometimes the greatest art is in response to somebody else’s pain. Was Gabriel reaching out to this woman from beyond in order to assure her that she could have been okay had she stayed with us? Sometimes the results are disastrous (think Don McLean’s sappy “Starry, Starry Night”, about Vincent Van Gogh, with the line “You took your life like lovers often do” followed later by “This world was never meant for one as beautiful as you”). It’s difficult not to be entranced and seduced by Sexton and her mastery of and comfort with the camera. She was made for black and white documentary. Look at her perfectly chiseled face, dark hair flowing as she gestures and performs. There was nothing shrinking about this poet when she was on, nothing submissive, making the end result of her final choice that much more tragic.

Poetry in all its forms can be a tricky, difficult beast, obtuse and accessible and ponderous at the same time. The romance of the tortured poet who chooses their own time and place to slip this mortal coil is a guaranteed ticket to literary immortality. The male writer suicide (among many being Hemingway, Mishima, John Berryman) is often more quickly forgiven than the female. The arguments for song lyrics as a legitimate poetic form are too tired to re-hash. Sexton took her life on 4 October1974, a little more than a month before her 47th birthday. Gabriel continued after 1986’s So to sporadically write and perform challenging music and film scores that tapped into the dark recesses of mortality, temptation, fear and love. There were no more major hits. He had his time at the top of music video stardom, and then it was over. Somewhere, somehow, Gabriel and Sexton with her father are still searching for Mercy Street, riding in the boat during twilight, awaiting what happens next.