‘What’s it all about?’ is the philosophical question that we have surely asked ourselves. However, for a long time it was not a question one would expect to find posed in a mainstream popular song. If we trace the development of commercial music and examine the lyrics that emerged from Tin Pan Alley and its aftermath we find the dominant theme is love – celebrated, desired or lamented. What we admire about this music is the skill of its composers; what we enjoy is the mood it creates.

In the 1960s and after, popular song started to address ‘the meaning of life’. One could detect the shift in focus in a song like ‘Alfie’ (1966) by Hal David and Burt Bacharach, which begins with the philosophical question above. It is a song about love, but it is also about the nature and purpose of being human: ‘What’s it all about, Alfie?’ The eponymous character (Michael Caine in Lewis Gilbert’s Alfie) is essentially selfish, and his attitude toward love is exploitative. The singer, having fallen in love with him, asks: ‘Are we meant to take more than we give, / Or are we meant to be kind?’ She then draws this sombre conclusion: ‘And if, if only fools are kind, Alfie, / Then I guess it is wise to be cruel / And if life belongs only to the strong, Alfie, / What will you lend on an old golden rule?’

Alfie’s basic assumption about human relationships is the survival of the fittest. What then of traditional standards of human conduct? The singer can only assert the importance of true love. As we have already acknowledged, that is the main theme addressed in popular music throughout the earlier decades, but here it acquires a new resonance and profundity.

As popular music became more philosophical in the 1960s, so did it begin to celebrate a figure not previously considered: the guru. Spiritual themes became familiar, and Eastern wisdom became a recurrent reference point. This turn to the East coincided with a new interest in Indian music, but it also offered a new perspective on perennial human concerns. Here I want to discuss four important figures in popular music who made this turn and sought the guidance of a guru.

Brian Wilson

Apart from being a work of musical genius, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (1966) is remarkable as a meditation on the search for meaning. Though there were some upbeat songs, the general spirit of the album is one of melancholy and yearning. The group’s most important member, Brian Wilson, was the chief composer of the music, and he was also an important contributor to the lyrics. It was he who decided to work with a lyricist who was not a member of the band, namely Tony Asher.

Wilson believed Asher could articulate the themes that were preoccupying him. ‘I Know There’s An Answer’ is representative. It had started life under the title ‘Hang on to Your Ego’, Wilson’s challenge to the shallow individualism of the age, and then it took lyrical shape with the help of Asher.

There’s a seeming contradiction in the lyrics. On the one hand: ‘I know so many people who think they can do it alone / They isolate their heads and stay in their safety zones’. On the other, the singer himself declares: ‘I know there’s an answer, / I know now but I have to find it by myself.’ Is the person criticising others for being self-centred guilty of the same charge? I think not. The contrast is between those who ‘come on like they’re peaceful / But inside they’re so uptight’ and an individual seeking to go through and beyond his solitude to a genuine form of enlightenment. Though this would initially be an individual quest, his trust is that it would open him up to a wider horizon beyond the limits of his ego.

The song’s mood is that of individual angst, but the sheer power of both the music and the words give due weight to what amounts to philosophical speculation about the point of human existence. The sense of urgency in the song, as the need for an answer becomes more difficult to resist, surely resonates with listeners.

We still need to indicate the ‘answer’ that Wilson and the rest of the group found. In late 1967, they went to hear an Indian guru, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, expound the benefits of his form of meditation. They decided to be initiated into the practice, which involved simply repeating a sacred ‘mantra’. The following year they released Friends, the final track of which was called ‘Transcendental Meditation’ – the Maharishi’s name for the practice. Wilson and two other members of the band, Mike Love and Al Jardine, were the composers of that song. The lyrics could not be clearer: ‘Transcendental meditation / Can emancipate the man / And get you feeling grand. / It’s good.’ This was in keeping with Maharishi’s claim that transcendental meditation was beautifully simple to practise.

However, Wilson was not so sure that transcendental meditation was the ‘answer’. Far from gaining spiritual enlightenment, he was plagued by depression alongside physical decline. In the mid-’70s, Wilson’s family became so concerned about his condition that it sought the help of a psychologist, Eugene Landy. Initially, Landy was a beneficial influence, but gradually he took control of Wilson’s life and work in every detail, rendering him a helpless dependent. Eventually, the family sued the psychologist, forbidding him to contact Wilson; not long after, Landy lost his licence. It was now possible for Wilson to begin his recovery.

One might say that Wilson followed one guru in the late ’60s, the Maharishi; in the ’70s and ’80s he followed another, Eugene Landy. The difference was that the Maharishi did come from a genuinely Hindu tradition and did offer a legitimate practice, whereas Landy was propounding a bogus solution to Wilson’s suffering.

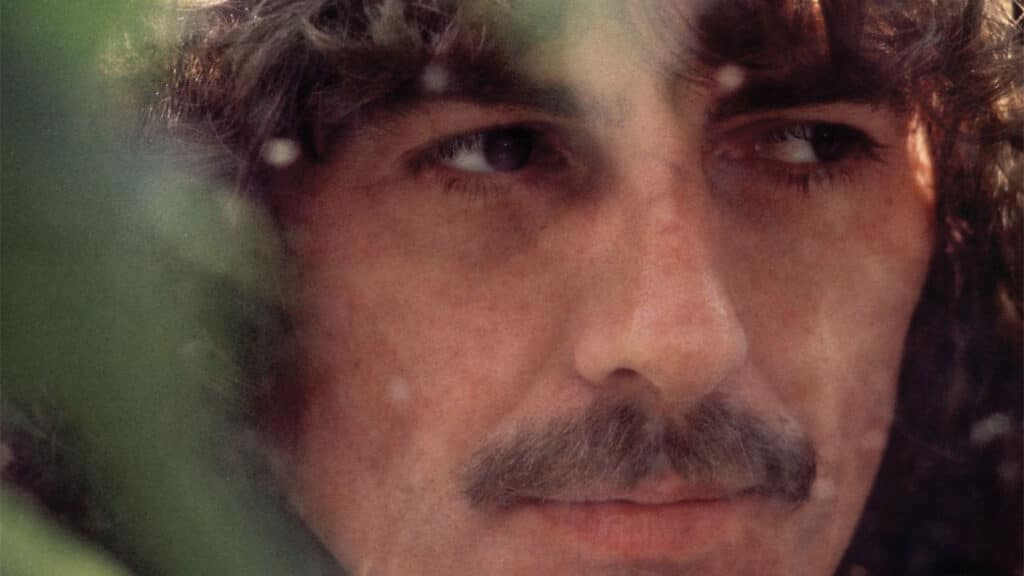

George Harrison and John Lennon

Like the Beach Boys, the Beatles were converted to transcendental meditation in the late 1960s. George Harrison and John Lennon were particularly fascinated by the movement. However, their stay at the Maharishi’s ashram in Rishikesh, Northern India in 1967 ended on a sour note when they accused him of improper conduct. Nevertheless, the experience had a lasting effect on Harrison, who was now fascinated by Indian religion.

The following year, he had a fortuitous meeting with A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. Harrison became deeply involved with the movement and supported it financially for a long while after. Though he had been impressed by the Hindu spirituality which he had gleaned from his time with the Maharishi, he was eager to commit himself to a specific doctrine and a specific deity. Prabhupada, who taught that one could become liberated by dedicating oneself to Krishna, the avatar (or incarnation) of the Hindu god Vishnu – and in particular by chanting his name – became, in effect, Harrison’s guru.

From this distance, we might think that Harrison’s advocacy of the ‘Hare Krishna’ chant dates him drastically, as uncritically adhered to the hippie movement, with its trendy turn to the East. In fact, his solo album All Things Must Pass (1970) is the work of someone who has immersed himself in Hindu metaphysics, and in so doing wishes to redeem the hippie philosophy by purging it of its more decadent, self-indulgent tendencies and reaffirming the authentic religious tradition which had become trivialised in the decade of ‘flower power’. In short, he is calling upon his listeners to surrender to the absolute reality of the Godhead rather than clouding the mind with an inordinate amount of drugs.

The most famous track on All Things Must Pass is ‘My Sweet Lord’. It is a song of surrender to Krishna. The melody carries the conviction rather than any particular part of the lyric. Harrison’s plea – ‘Really want to see you, lord / But it takes so long, my lord’ – is sustained by an insistent rhythm that conveys the feeling of surrender. Boldly, Harrison chooses to convey this mood by chanting alternately ‘Hare Krishna’ and ‘Hallelujah’. Far from evincing shallow eclecticism, this affirmation of the affinity between the Christian and Hindu paths is in keeping with the conviction of a ‘perennial philosophy’, a mystical wisdom underlying apparently divergent doctrines. Harrison, while committed to Hinduism, is simultaneously honouring the Christian path. He is free to do so because the essence of Hindu mysticism is that the Godhead is universal, with each specific god offering a focus for devotion. Thus, all avatars are to be revered: Jesus as well as Krishna.

In the album’s title song, Harrison commends the wisdom of Prabhupada, stressing the transience and insubstantiality of temporal existence: ‘All things must pass / None of life’s strings can last.’ Mysticism should not be sought as a momentary, sensational experience, but as part of a spiritual quest; and spirituality is best nourished by keeping in touch with its religious roots.

Cynics that we are, we do not expect popular singer-songwriters to follow the same spiritual path forever once they’ve declared their affiliation to a particular system of belief. Harrison, however, may be seen as totally consistent, espousing Krishna Consciousness right through to his death in 2001. His case forms a contrast with his fellow-Beatle John Lennon who, in the very same year as All Things Must Pass, released Plastic Ono Band, which articulated a mood of complete disillusionment. Lennon’s earlier dedication to the Maharishi’s movement was now forgotten, and religion itself was rejected.

Thus, in the song ‘God’, Lennon declares the idea of a deity to be merely ‘a concept by which we measure our pain’. The main body of the song consists of a list of all the people, philosophies, and practices that he wishes to discard: ‘Don’t believe in … ‘Magic … I-Ching … Bible … Tarot … Hitler … Jesus … Buddha … Gita … Mantra’ – culminating in the defiant declaration that he doesn’t even believe in the Beatles. By way of conclusion, he tells his listeners that the ’60s, which they thought had brought liberation, was a sham decade. ‘The dream is over’, and Lennon himself, who was ‘the dreamweaver’, is now simply ‘John’ – leaving them to ‘carry on’ as best they can.

Again, in ‘I Found Out’ he asserts the importance of coming to terms with one’s own humanity instead of looking to others for answers. Hare Krishna is no use to us, he declares, and the whole idea of following a spiritual guide is dismissed: ‘There ain’t no guru can see through your eyes.’ Drugs are just another way of avoiding reality: ‘I seen through junkies, I been through it all. / I seen religion from Jesus to Paul. / Don’t let them fool you with dope and cocaine — / No one can harm you, feel your own pain.’

This is a challenging album, full of savage irony (does ‘Paul’ refer to a certain Paul McCartney, to St Paul, or to both?), but I wonder if it entirely evades the model we’ve been following. It was composed and recorded by Lennon immediately after undergoing ‘Primal Scream’ therapy, in which he had been encouraged to regress emotionally, re-experiencing the trauma of birth and early childhood, under the guidance of the radical psychotherapist Arthur Janov. As such, Plastic Ono Band might be seen as an extended testimony to the philosophy of Janov, who had told him that religion was a dangerous diversion: that he had to accept material reality, and to understand the source of his ‘pain’, without recourse to any spiritual perspective.

Thus we see how hard it is to follow a new path without also following a guru, even if his message is anti-guru.

Van Morrison

In 1996 the Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison was invited to provide a ‘blurb’ for Questioning Krishnamurti, a volume of dialogues between the Indian sage, Jiddu Krishnamurti, and various philosophers and religious leaders. Many of Morrison’s admirers would not have known that name; but certainly that man had a huge influence on Morrison himself.

Jiddu Krishnamurti, born in India in 1895, was in his youth adopted by the Theosophical Society, which decided that he was a ‘world teacher’, and declared him head of ‘the Order of the Star in the East’. In 1929, however, Krishnamurti rejected not only this honour but also the whole idea of a religious organisation. He made this defiant statement: ‘Truth is a pathless land: man cannot come to it through any organization, through any creed, through any dogma, priest or ritual, nor through any philosophic knowledge or psychological technique. He has to find it through the mirror of relationship, through the understanding of the contents of his own mind, through observation and not through intellectual analysis or introspective dissection.’

Thereafter, he dedicated his life to opening people’s minds to the importance of awareness: something possible only in the present moment, when the mind is free of definition, doctrine, dogma – and, indeed, of thought itself. Only through awareness of what is actually there before and around us, of what is rather than what once was or what should be, can spiritual liberation take place. For consciousness is not a matter of time but of eternity, which can only be known with a ‘silent mind’ which is open to this very moment. Past and future are the enemies of true awareness, which can only take place in the here and now. Far from being a religious authority, Krishnamurti insisted that all he was doing was encouraging people to be free.

We might situate Krishnamurti by way of comparison with Arthur Janov. Both were against the whole idea of a guru, but for different reasons. For Janov, it was because he saw religion as a form of repression which distracted people from recognising and reliving the pain of the past, in order to release themselves from it. For Krishnamurti, it was because the whole idea of following an authority only prevented people from opening themselves up to the silence of the present moment, which is the only true means of spiritual liberation.

As requested, Morrison wrote for the book: ‘I feel the meaning of Krishnamurti for our time is that one has to think for oneself and not be swayed by any outside religious or spiritual authorities.’ This endorsement was continuous with the title of an album released by Morrison a few years earlier: No Guru, No Method, No Teacher (1986).

The central song is ‘In the Garden’. The singer addresses a loved one who is full of sorrow: he offers reassurance and hope. The return to the garden will, he says, begin the healing process. So it proves: ‘And then one day you came back home. / You were a creature all in rapture. / You had the key to your soul / And you did open that day you came back to the garden.’ It is a moment of revelation: ‘The olden summer breeze was blowin’ on your face. / The light of God was shinin’ on your countenance divine…’ ’

We are to understand that they are meeting in a specific place, but it has archetypal meaning for them. The notion of returning to a garden is recurrent in religious thought. We think of the earthly paradise, or ‘Garden of Eden’, which we are to believe was originally intended as the home for humanity. The inference is that, in that world and at that time, humanity, nature and God were all in sympathetic relationship. Adam and Eve may have lost this pastoral bliss because of sin, but humanity retains its nostalgia for paradise.

Morrison invokes this spiritual model in a song of healing, in which he reassures his companion that they have both been granted spiritual awakening: ‘Born again you were and blushed, / And we touched each other lightly, / And we felt the presence of the Christ / In the garden.’ The essential moment of awakening is summed up as follows: ‘And I turned to you and I said: / ‘No guru, no method, no teacher / Just you and I and nature / And the Father in the garden.

At this point the listener who has followed Morrison’s work and who is familiar with his thinking may feel that there is a contradiction in such an utterance. On the one hand we have imagery drawn from the Bible, and specific reference to the Christian faith; on the other we have the wisdom of Krishnamurti, which counsels us to go beyond theology and open up our minds to the present moment. However, perhaps we could accept it as a vital paradox: doctrine becomes dead unless it is in touch with nature, unless it is guided by love and unless it is informed by imagination. There is ‘no guru, no method, no teacher’ that can embrace the sacred mystery of existence.

Standing back from the whole song, we can see that it gains its effect by mediating between different spheres: the music and the mysticism; the Christian imagery and the power of pure awareness; the desire to go back and the readiness to become awake in this very moment. The guru may not be needed, but we may draw on his wisdom in order that our religious faith may not become deadened by dogma. We have to realise the spirit, not follow the letter.

Morrison issued a significantly titled album in 1991: Hymns to the Silence. The title track puts our above discussion into perspective:

The singer wants to ‘go out in the countryside, / Oh sit by the clear, cool, crystal water, / Get my spirit, way back to the feeling. / Deep in my soul, I wanna feel / Oh so close to the One, close to the One …’ That is why he keeps singing his ‘hymns to the silence’. The sound and the vision, the beauty of nature and the power of the divine, the song and the revelation: all are contained in that central paradox of that phrase.

Looking back over our discussion, we might say that Morrison has a much more subtle notion of spiritual awakening than the other songwriters we have discussed. We might also say that he has a much more subtle understanding of the role of the guru, and what it means to live with or without one. However, we need to also take account of the hunger for meaning evident in Brian Wilson’s music: without that, the figure of the guru loses its importance. Again, by contrasting John Lennon’s and George Harrison’s development after their experience with the Maharishi we can see that the adoption of a particular guru is an existential choice.

Perhaps many of us who once might have followed a specific guru and adopted a specific practice are more inclined to get our spiritual wisdom from popular song. For example, some of us spend much of our leisure time pondering religiously the lyrics of Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, and Joni Mitchell. Have the singer-songwriters themselves become our gurus?

Works Cited

Krishnamurti. Commentaries on Living: Second Series. 1958.

Krishnamurti. Questioning Krishnamurti: Jiddu Krishnamurti in Dialogue. 1996.