“Don’t Call it Punk.” — Seymour Stein, President of Sire Records, 1977.

Few today would use the expression “New Wave” to describe early ’70s proto-punk bands like the Stooges and the New York Dolls, but it was for them that the term was initially applied in the music papers. Later, when media outlets began covering the CBGB bands, the label lingered, often used interchangeably with “punk”. Soon the British media were also oscillating between the two tags in describing their home-grown musical upstarts, with influential voices like Malcolm McLaren first attempting to steer journalists towards using “New Wave” before rejecting it in favor of “punk”. For him, this rhetorical two-step reflected his dual concerns of maximizing the exposure of the Sex Pistols while also maintaining their anti-establishment identity.

Similar concerns came to a head in 1977 when punk—thanks largely to the pranks and antics of the Pistols—grew increasingly associated with violence, offensiveness, and anti-social behavior. For those in the industry intent on marketing punk as the next big thing, such a negative image proved a barrier when convincing radio programmers, television producers, concert promoters, and mainstream media to be participants in its coverage and dissemination. For Seymour Stein, head of Sire Records, the solution was not to defend punk rock against its detractors, but to ride a different wave, the New Wave.

With the Ramones and the Talking Heads on his roster, Stein was convinced that his bands and others could invigorate the staid rock world as the British invasion bands once had in the early ’60s. His challenge was in how to circumvent punk, which had become increasingly associated with aberrant conduct, and thus, diminished financial prospects. Being labeled as “punk” by prior designation, Stein saw his bands as trapped in a media cage, found guilty by association when stories surfaced about the Sex Pistols swearing on TV or punks fighting at concerts or in the streets.

In October 1977 he acted, unleashing a “Don’t Call It Punk” campaign on behalf of his Sire bands. This he supplemented with a letter sent to FM radio programmers requesting they use his preferred term of “New Wave”. Punk, he argued, was an offensive label, the equivalent of using “race music” to describe the rhythm and blues of the early ’50s (Cateforis, Theo, Are We Not New Wave? Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s, University of Michigan, 2011, p.25). Stein made “New Wave” a term that could compete against “punk” in the marketplace of genre representations, industry insiders now given the means to avoid the baggage the latter carried. During this process punk itself underwent a brand re-evaluation, its harder factions re-named “hardcore” or “oi” and its more experimental ones, “post-punk”. The more commercially viable, industry-preferred bands were gathered up into the New Wave camp, even if they had not been perceived or described as such a few years earlier.

Active since 1973-74, (proto-)punk bands like the Modern Lovers, Blondie, Talking Heads, and Devo were all (re-)categorized as New Wave post-77. They earned their new moniker not from a commonality of sound, but from all of them not sounding anything like Ramonic punk. Punk rock, by 1977, had become known for its distortion-dense three-chord guitar assaults, but these bands had a more stripped-down sound, with rhythms and chord changes less beholden to classic rock ‘n’ roll structures. And while irreverence and innovation were still central to songwriting ambitions, overt aggression and extreme emotions were tempered by more self-conscious intellectual and/or ironic dispositions. More pop and less punk, more school and less streets, these players were more relatable for mainstream audiences, yet were still sufficiently eccentric to be situated within punk’s outsider identity zones. Their characteristic alienation, often expressed as rage by punk rockers, took on a more nervous, introspective form in New Wave’s articulations.

That so many of the early New Wave artists went to art school is neither coincidental nor incidental. There—particularly those studying design—they learned the commodity and marketing aspects of art (theory) that would educate them in using subversive strategies for profitable ends, something ex-art student Malcolm McLaren specialized in when pursuing his own “cash from chaos” rock ‘n’ roll “swindles” with the New York Dolls, the Sex Pistols, Bow Wow Wow, and as a solo artist. Less obligated to punk’s more radical resistance postures, however, New Wave bands took many of their cues from David Bowie and Brian Ferry, prior performers skilled in using sound, style, and persona in combinations both alien(ating) and commercially appealing.

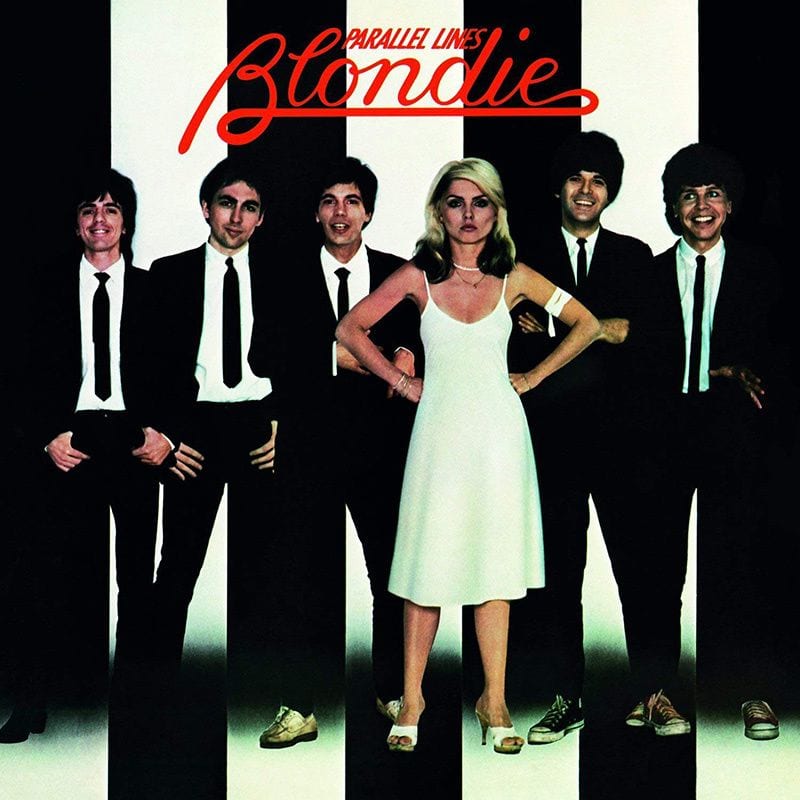

Punk and New Wave are often fairly noted for breaking from rock’s past, but those breaks were largely from ’70s styles like prog, MOR, and classic rock. Mid-’60s music, on the other hand, always loomed large, and nowhere more so than in Blondie. Their pillaging of ’60s “pop” clichés (the blonde fetishism, the girl group melodies, the big beats) were often more tolerated than embraced by the CBGB in-crowd, though their recycling was always sufficiently off-kilter to be appreciated as camp if not subversive. Such ambivalent reception allowed the band to maintain their punk membership while being open to accommodation by more mainstream industry forces.

This co-option reached its completion with the release in late 1978 of Parallel Lines, the album that made Blondie international superstars. Meticulously produced by pop maestro Mike Chapman, the album sees the band performing a balancing act (so common to so many early New Wave bands) by fusing multiple genres to pop, producing a sonic panorama taking in upbeat pop-punk (“Hanging on the Telephone”), 1960s-styled pop beats (“Pretty Baby”), pop ballads (“Sunday Girl”), and disco-pop (“Heart of Glass”). This pop-oriented smorgasbord elicited conflicting reactions from different constituencies, with punk purists crying “sell-out” but new New Wavers embracing a sound that, in contrast to the surrounding rock and pop of the era, sounded fresh and exciting. Meanwhile Blondie’s label, Chrysalis Records, celebrated the discovery that old punk could bear New Wave fruits, as the record topped the UK charts and reached number six in the US on its way to selling over 20 million copies.

As in the US, in the UK the term “New Wave” floated in the same waters as “punk” before establishing a separate identity in late 1977, thanks, according to Johnny Rotten, to its ubiquitous use by “poncey journalists” (Lydon, John. Rotten: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, Picador, 1994, p.253). The August release of Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True forced those journalists—as well as other industry insiders—to reconcile that record’s punk-inspired pounding beats, garage rawness, and “brutal sarcasm” with its songs’ sophistication, intellect, and stylistic diversity (Marsh, Dave, The Heart of Rock & Soul, Plume, 1989, p.142). Punk but not punk, the critics settled on New Wave.

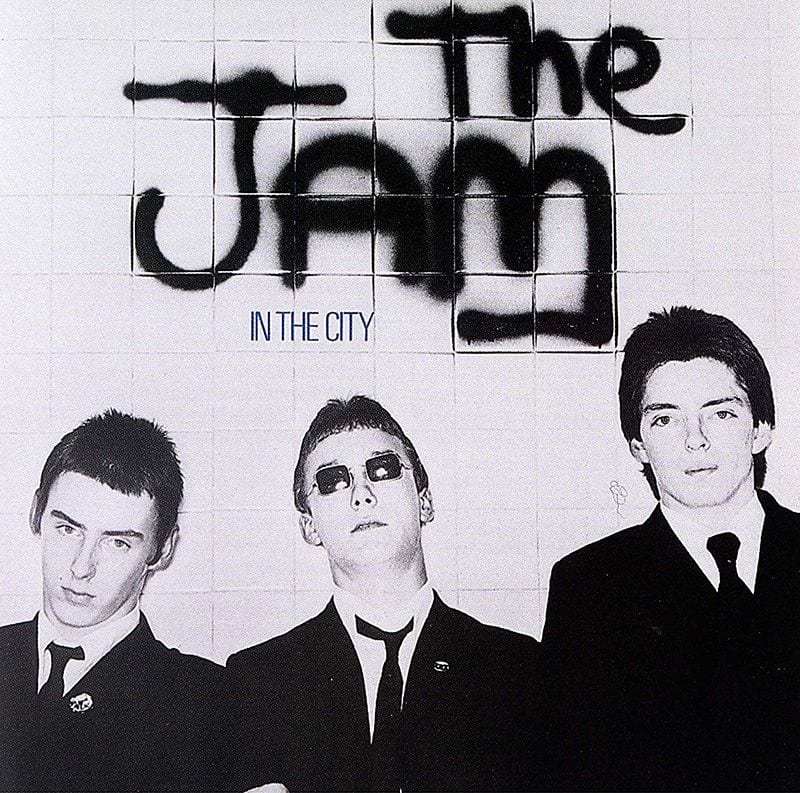

Generalizations that New Wave was just a kinder, gentler punk were dashed by the likes of Costello, whose bitter political rhetoric—whether personal or social—remained front-and-center throughout his career. The Jam, another break-out band of 1977, were similarly socially-attuned. Paul Weller’s politics, though, were initially out-of-step with his peers, as he teased and poked at the trendy socialism and anarchism in the British punk scene. “What’s the point in saying ‘destroy’?” he asks in “All Around the World”, taking a thinly-veiled pot-shot at the Johnny Rotten of “Anarchy in the UK”. Like Costello, the Jam played an angry form of pub and mod rock that allowed them to “coast in the slipstream” of punk without getting trapped in it (Savage, Jon, England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond, St. Martin’s, 2001, p.334). By the close of 1977 the most commercially successful bands to emerge from the punk insurgency were not the Sex Pistols and the Clash, but rehabilitated-as-New Wave acts the Jam and the Stranglers.

As the diaspora brought us bands as stylistically diverse as Talking Heads, Blondie, the Jam, and the Stranglers, it became apparent that the term “New Wave” was inadequate as a descriptor of a style, yet quite effective as a marketing device for the more accessible outliers of the punk movement. In the UK the popularity of these bands sparked a backlash of even greater force than had occurred in the US. Driven partly by jealousy and partly by perceptions that New Wave was diluting “real” punk, leaders of the punk old guard, led by Joe Strummer and Johnny Rotten, hit back. The latter dismissed New Wave as “flimsy” and “vacuous”, adding “there’s no energy to it” (Lydon, p.254).

Even more irritating to Rotten were the opportunism and cut-throat ambitions of these bands, all of whom, he felt, were willing to lie down with the sleaziest of industry types (record company executives, managers, DJs) in order to attain stardom. In Rotten’s words, “They were all just imitators jumping up on our bandwagon and trying to mellow it out so they could go for the big bucks and the easy life” (p.254). Strummer was equally scornful in his assessment of New Wave, taking aim at the Jam (and others?) in the Clash song “(White Man) in Hammersmith Palais” with the lines, “They got Burton suits, ha, you think it’s funny / Turning rebellion into money.”

Ironically, the “Conservative” Jam later went on to release songs with a socialist bite—like “Eton Rifles” and “Town Called Malice”—that Strummer would have been proud to pen. In 1977, though, the Jam were content to be contrarians to punk’s agit-prop dogmatism and profited by keeping their distance from it. Others, like Generation X, were more brazen in their un-friending of punk in pursuit of the rewards of New Wave. In 1977, long before singer Billy Idol became the poster boy for punk sell-outs, his guitarist Tony James regularly sported a T-shirt emblazoned with the slogan, “Sold Out to Record Company”. Few of the band’s peers regarded this as an ironic gesture.

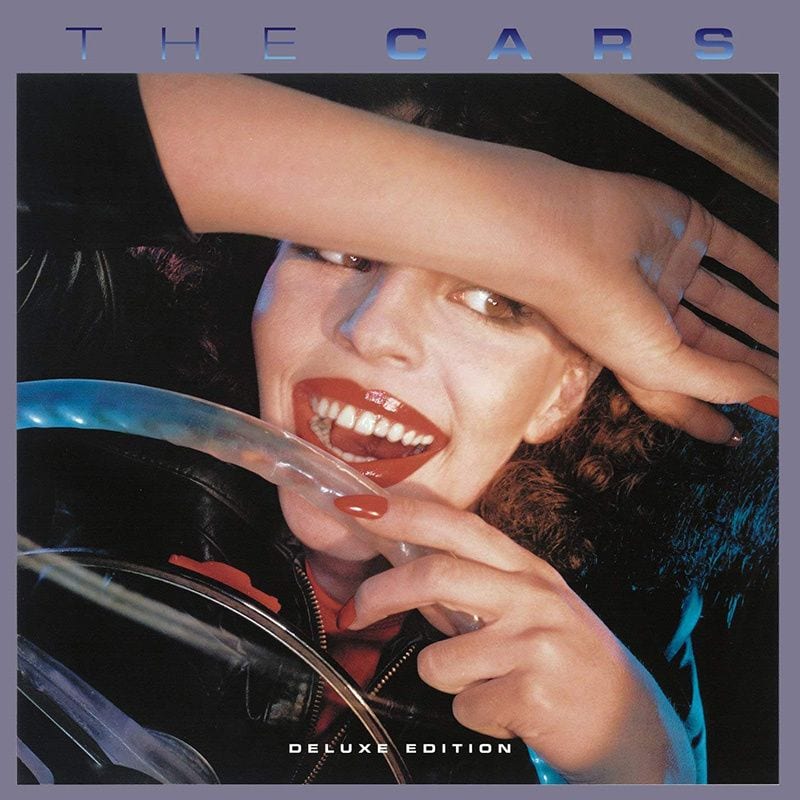

If 1977 was New Wave’s breakout year, by 1979 it had become an industry force, all but replacing punk as a viable vehicle or term of currency. Victorious were those bands like Blondie and Talking Heads that had been laboring in the trenches of the CBGB punk scene for years, and Brits like Elvis Costello and Ian Dury who had been doing likewise on the pub rock circuit. Talking Heads and Costello particularly caught the ears of (major) labels, the rock press, and even some radio stations, leading to sound-alike acts like the Knack and Joe Jackson being snapped up and promoted in their image. First among this next wave of New Wave were the Cars, a band that played an urgent power pop that could pass as punk lite, but included synthesizer coloring that gave off a futuristic aura. Their slick production and traditional romantic lyric themes made “Just What I Needed” and “Best Friend’s Girl” soundtrack tunes of 1979, while these songs’ robotic rhythms, synth effects, and clipped vocals were just weird enough to place the band in the New Wave rather than rock or pop category.

The Cars begot the Knack, whose Get the Knack album was the major New Wave hit of 1979. Its lead single, “My Sharona”, topped the Billboard charts in August of that year, as did the album for five consecutive weeks. This was New Wave’s Saturday Night Fever, quips Theo Cateforis (p.38). The Knack lacked the jagged edges of the Cars, but like them had a fondness for ’60s power pop. Their mod look, Dave Clark Five rhythms, and early Beatles melodies gave notice that just about any new band with an upbeat backbeat—and wearing an Italian suit and skinny tie—could now be a candidate for being promoted as New Wave. The Police, the Jam, and XTC were all elevated by the subsequent industry feeding frenzy, while established rockers like Billy Joel, Peter Gabriel, Pete Townshend, and even Paul McCartney rode that elevator, too, orienting their songwriting in more New Wave directions. Although not exactly the equal of the British invasion as Seymour Stein had hoped, New Wave demanded attention in 1979 as the only innovative and energized music in an otherwise bland mainstream rock environment.

New Wave hit a lull in sales during 1980, but rather than a sign of decline this proved to be just a calm before the storm ushered in by the arrival of MTV a year later. Scrambling to find new music, visually intriguing personalities, and bands with ready-made videos to fill up its 24-hour, seven days a week channel, MTV went where the action was: to the New Wave.

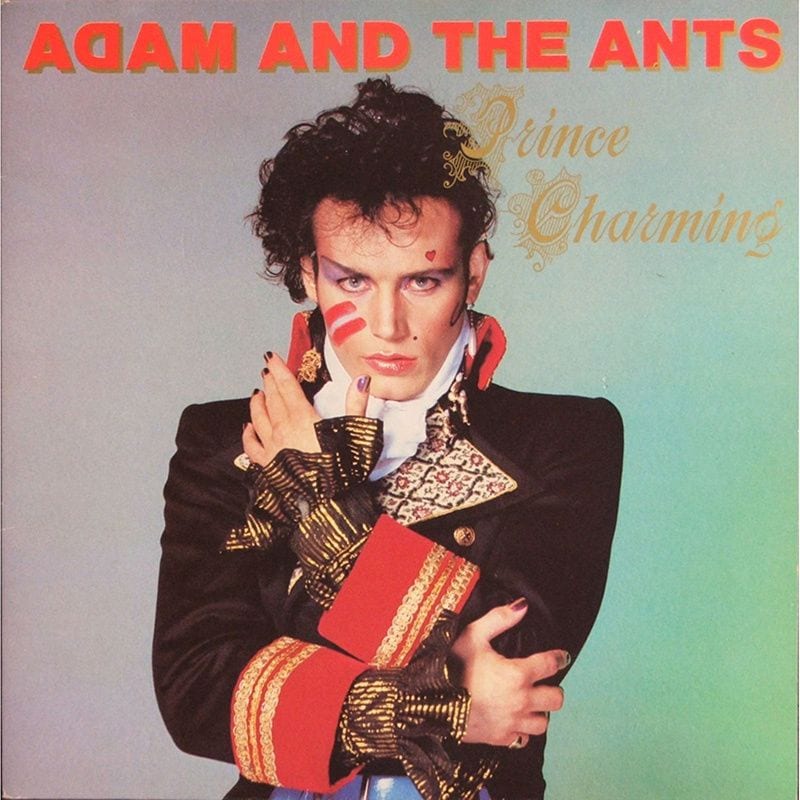

The visualization of rock music that MTV brought about benefited a number of existing New Wave bands, introduced new ones, and broadened the scope of the genre almost beyond recognition. For some, MTV’s prioritization of image over sound and pop over punk sensibilities all but destroyed any meaning New Wave once had. Bill Flanagan comments, “Bit by bit the last traces of punk were drained from new wave, as new wave went from meaning Talking Heads to meaning the Cars to Squeeze to Duran Duran to, finally, Wham! And that was a sad day” (Cateforis, p.63). Victims of the MTV revolution were those artists unwilling or unable to alter their visual appearance to suit the new demands. Drab pub rock stalwarts from early New Wave faded from view in the early ’80s. By contrast, ambitious glam-rebel also-rans like Adam and the Ants and Generation X looked in the mirror, then took advantage of the MTV-friendly good looks staring back at them.

* * *

Additional Reading on PopMatters:

“Mad World: An Oral History of New Wave Artists and Songs That Defined the 1980s”, Lori Majewski, Jonathan Bernstein (15 May 2014)

“Sex Pistols: Pun(k)s, Pranks, and Provocations”, Ian Ellis (20 Mar 2012)

“Are We Not New Wave?: Modern Pop at the Turn of the 1980s”, Theo Cateforis (21 Jul 2011)

“Who Owns Punk History?“, David Ensminger (15 Dec 2010)