A writer’s lines have a tendency to fly away into the great wide open once their creator has slipped through this mortal coil. They’re either improperly affixed to memes as a way to connect the writer to a cause, or they become permanently connected with a national event that will have troubling effects on the world.

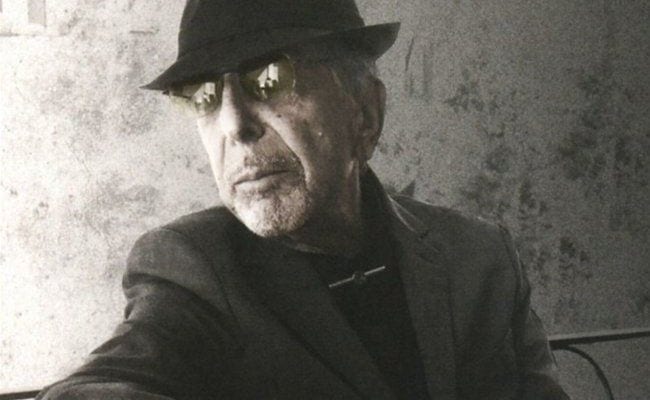

In the case of Leonard Cohen, whose 7th November death (announced to the world on the 9th of November), many lines from his greatest songs were taken as commentary on the election of Donald J. Trump as 45th President of the United States of America.

Take the cynicism of “Everybody Knows”, the doomsday prophecies of The Future, and you get a picture of hopelessness and surrender in the midst of a permanent midnight. In “You Want it Darker?”, released just three weeks ago, the 82-year-old Cohen’s brutally raw reflection on his own imminent demise can easily be taken as an examination of the political world condition:

Magnified, sanctified, be thy holy name

Vilified, crucified, in the human frame

A million candles burning for the love that never came

You want it darker We kill the flame

The lyrics of other songs, more easy to take, were also shared. Cohen’s 1992 release The Future, whose title track was almost unbearably grim, also featured a more hopeful plea for peace. In the generically titled “Anthem”, Cohen’s booming voice of God baritone rises with the strings and female backing vocalists with a simple plea:

Ring the bells (ring the bells) that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything (there is a crack in everything)

That’s how the light gets in

Perhaps he was inspired by a fellow Canadian, Bruce Cockburn, whose 1984 song “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” featured the beautiful simplicity of nothing worth having comes without some kind of fight / Got to kick at the darkness ’til it bleeds daylight. It wouldn’t be the first time great minds are so clearly are having a conversation with each other.

The Cohen lines kept coming, posted on twitter and Facebook, performed earnestly and otherwise as a way to cope with what many are seeing as the strange, bitter Trump-brand pill that needs to be absorbed because there’s no alternative, at least through the next four years. On the 12 November 2016 Saturday Night Live episode, performer Kate McKinnon, who had spent the past nearly two years satirizing the sometimes stiff formality of Hillary Clinton, started the program alone on the stage, sitting at a piano. She began playing the opening chords of Cohen’s “Hallejulah”, and at that moment it could have gone two ways: mawkish sentimentality or a focused and strong statement of determination. McKinnon finished the song, shortened but still featuring this stanza:

It’s not a cry that you hear at night

It’s not somebody who’s seen the light

It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah

As the last note finished, McKinnon addressed the camera and said: “I’m not giving up, and neither should you.” The performance was remarkable for two very clear reasons. Through the course of McKinnon’s performance as Clinton, she had at times emphasized Clinton’s stiffness and seeming inability to connect to or relate with the common people. That was her job as a comic satirist, but astute viewers could see something deeper in her final bow as Clinton.

Her address to the camera seemed to be directly connecting with the thousands of people protesting in the streets in these painful days after Trump’s win and motivating them to continue as we all adapt to the unbearable coldness of this new normal. This was not a call to revolution, rage, or retribution. It was a call for self-empowerment.

McKinnon and SNL managed to put “Hallejulah” into a realistic, proper context. It’s a song of mourning. The full version is erotic and regretful, a perfect mixture of the sacred and profane. Of all the songs in Cohen’s canon, “Hallejulah” has been the most bowdlerized and sanitized, misinterpreted as strictly a song of faith and worship. For some the name Hallejulah is a call to the Lord, to God, whatever name best fits the purpose, for others it’s a cold and broken Hallejulah. I’ve never understood how or why it’s been relegated to a song of Christmas worship. For those three and a half minutes the night of 12 November 2016, it became something better.

Song lyrics constantly slip in and out of the atmosphere for those open enough to catch them, and in these times they’re more important than ever. Leonard Cohen, like David Bowie last January, died almost immediately on the heels of releasing a final work of stark mortality, grief, and beauty. That’s where the synchronicity plays a role. What did they know? How will their music be applied to these times? Were they preparing for something in another stage, in a different world?

At a “#lovetrumpshate” Rally on Boston Common last Friday, 11 November, the crowd sat in a large circle and a series of unamplified people rose to motivate their fellow citizens to mobilize, unionize, find strength in solidarity. They seem mostly young, and mostly white at this point, which doesn’t bode well for a universal Progressive Movement. My reaction to this Rally and others I’ve attended over the past few years, for Black Lives Matter and Occupy, was the same: what’s their thesis? Where is the structure? Who are the leaders? Perhaps it’s the teacher in me, but I just wanted a unifying theme.

It was then, as I wandered the crowd looking for great photographic moments, that I saw an older man in the middle if the circle loudly trying to start the young people in a chorus of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going on?” Most didn’t seem to know it.

The best songs for any movement, the most suitable anthems, are usually rousing and energetic. For the most part, that wasn’t in Cohen’s bag of tricks, at least in his original versions. What Cohen did have, in ways sometimes much clearer than his contemporaries, was an understanding that recognizing the darkness was never surrendering to it.

As the new regime prepares to take over the White House, already compiling its Enemies List and probably plotting regular calculated revenge, I want the young people to hear this stanza from Cohen’s 1988 “Tower of Song”. It’s humorous, self-deprecating, but also deeply raw and prescient. Cohen isn’t attributing this mighty judgement to anything religious, but that doesn’t matter. It may be mighty, but it can’t be final.

Now, you can say that I’ve grown bitter but of this you may be sure

The rich have got their channels in the bedrooms of the poor

And there’s a mighty judgment coming, but I may be wrong

You see, you hear these funny voices in the Tower of Song