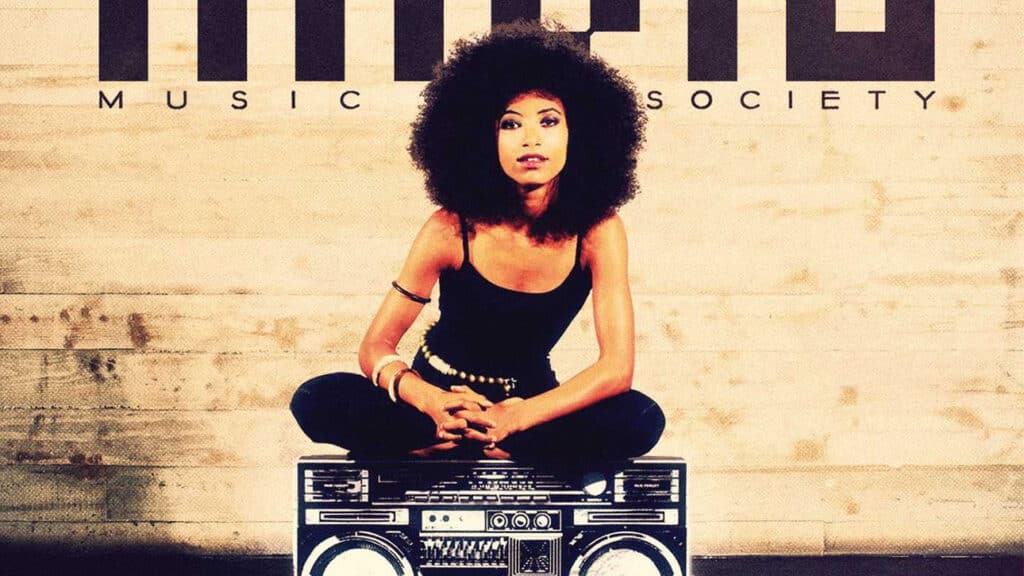

Before Radio Music Society came out in 2012, we knew who Esperanza Spalding was, but we didn’t have any idea where she was headed. With a decade of hindsight, the album looks like a hinge in her career as she veered toward modern forms of art song and performance. This recording—which debuted at number ten on the Billboard 200 chart (and, of course, number one on the jazz chart)—was her apex in deftly blending jazz and soul into something still tied back primarily to the terrain roughly and gloriously defined by Louis Armstrong and Ray Charles.

A triple musical threat as a singer, virtuoso bass player, and excellent composer, Spalding hit the public’s eye with a great story in hand. Like Wynton Marsalis a generation before, she was a prodigy of such promise that even listeners beyond the jazz tent were intrigued. She released a strong debut recording, Junjo, at the age of 22 while teaching at her alma mater Berklee College of Music. But many were intrigued when the hippest Nobel Peace Prize recipient in history chose her to perform in Stockholm when he was inducted in December of 2009. A head-spinning second album was out at the time, and Esperanza was even better than the first recording. The cool kids were suddenly hip to President Obama’s favorite acoustic bassist/singer. Then, in 2011, everyone knew her. Her third recording, 2010’s Chamber Music Society, was complex, ambitious, and even better. And it had that rarest thing of all: it was a jazz record that cut through into popularity without pandering.

Spalding won the Grammy for Best New Artist the following year—beating, let us not forget, Justin Beiber, Drake, and Mumford and Sons. The scene for a letdown had been set. But her following record would, wow, be her best yet.

Radio Music Society opens with “Radio Song”, a fitting thesis statement for the whole session in the form of a swaying funk tune that makes a virtue of complexity. Spalding uses every tool available: sharp horn parts for the American Music Program big band; slick vocal harmonies and countermelodies covered by Gretchen Parlato, Becca Stevens, and Justin Brown; a tenor saxophone solo by Daniel Blake and a delicious acoustic piano solo by Leo Genovese at his most Herbie-ish; and a rhythm section arrangement that pairs her own electric bass in dazzling, locked-in polyrhythmic groove with Terri Lyne Carrington’s drums. The swirling melodies are ear-grabbers interlocking in a danceable dazzle.

Surely this is just “the single”, and there will be plenty of filler to follow. Oh, actually, NO. The whole album is a refraction of this opening, each track potent in its own way.

Nodding, perhaps, to Chamber Music Society, “Cinnamon Tree” uses a violin and cello in an arrangement that snakes around Spalding’s electric bass line and Genovese’s unison electric piano left hand. The strings introduce the tune and take a lovely bow at the very end. Jef Lee Johnson shoots blues guitar all through the track’s mid-tempo soul. It’s also Spalding’s most purely silky vocal on the album, singing about a piece of nature that feels like a lover too.

Spalding is generous throughout Radio Music Society, making room for voices beyond her own. How about a very prominent improvising trombone from Jeff Galindo throughout “Crowned and Kissed”, a track produced by Q Tip from A Tribe Called Quest? How about giving prominence to Algebra Blessett’s lead vocal on “Black Gold”, a soul track featuring a hip horn part for trumpeter Igmar Thomas, tenor saxophonist Tivon Penicott and delicious organ colors from Raymond Angry—plus an inventive guitar/vocal solo from Lionel Loueke? When that tune changes keys at the end and brings in the Savannah Children’s Choir, it goes into a gospel zone you aren’t expecting.

Spalding also pays great attention to mentors and inspirations. “I Can’t Help It” is a tune by Stevie Wonder that we all loved when it first appeared on Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall in 1979. Spalding makes the track something extra by making it a feature for tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, in whose band she held the acoustic bass chair in a straight-ahead jazz mode. Lovano slips and slides around the tune with his woodiest, most feathery tone, all while Spalding dances through the arrangement with Jaco-esque joy. Similarly, the only other composition not by Spalding is “Endangered Species”, a 1985 tune by her mentor Wayne Shorter. Spalding wrote lyrics for the devilishly complex tune, and she hands much of vocal work to Lalah Hathaway.

Perhaps the best pure track on Radio Music Society is “City of Roses”. It was also co-produced by Q-Tip and the winner of a Grammy for instrumental accompaniment that year, deftly combining the big band (which gets a great mid-tune climax. Spalding locks in with Carrington again, but this time on acoustic bass, and there’s a lovely winding saxophone solo from Anthony Diamond. It’s another of the tunes here that suggests that Spalding has an inexhaustible well of sophisticated melodies from which to draw.

There are a few other songs here that demonstrate the ways in which this project was Spalding’s last to connect back to her jazz roots, purely. “Hold on Me” has a melody that is distinctively hers, but the arrangement is an old school pop arrangement that would have suited Nancy Wilson in the early ’60s—with the big band sounding lush and drummer Billy Hart giving depth to the swing feeling. “Vague Suspicions”, “Let Her”, and “Smile Like That” would be stand-out achievements on any other recording, but they are somewhat swallowed up by the soul power of the other tracks. All feature the brilliant drummer Jack DeJohnette, creating as many colors on his own as any big band. “Suspicions” is a gentle tone poem built on thrumming guitar/Rhodes and a feathery blend of flute and trombone as minimalist orchestration, all setting up a brief acoustic bass solo for the leader.

It may just be me, but “Smile Like That” might be Radio Music Society‘s most purely ingenious track, with Gilad Hekselman’s electric guitar locking in DeJohnette and the acoustic bass and a spare tenor sax/trumpet line—no keyboards needed here—in way that is fetching and catchy while also prefiguring the more guitar-based music that was ahead for Spalding in the near future.

After Radio Music Society, Spalding kept moving brilliantly forward. But a corner had been turned as she moved away from pop music and into less charted territory. Emily’s D+Evolution from 2016 is a masterpiece that incorporates more diverse influences into a stunning whole—Joni Mitchell’s expansive art song, hip-hop, metal, minimalism. In concert, it was performed as a musical theater piece, almost, with costumes and a set helping to elaborate on the character or alter ego (Emily is Spalding’s given middle name) in whose voice the whole album is sung. It sold less vigorously than Radio Music Society, however. Possibly that was the changing shape of the music industry rather than the music, but the truth is Spalding was no longer looking mainly to grab ears.

Each successive Spalding project has moved further away from convention, musically and formally. Exposure from 2017 was created from scratch in only three days, which were broadcast on Facebook Live, with the resulting music available “physically” in only 7,777 copies. The following year, 12 Little Spells was imagined as a suite with a body part corresponding to each song, which was each also accompanied by a video. Last year, Spalding released Songwright’s Apothecary Lab, which seeks to combine music with health practices, and she brought to performance Iphegenia, an opera (a real opera, not a jazz thing they were calling “opera”) with music by Wayne Shorter and her book and lyrics.

Several of these more recent projects have met with general success—12 Little Spells won the Grammy for Best Jazz Vocal Album—but they have taken Spalding in a different direction. That’s not a complaint. In many ways, we know that being a “jazz singer”, particularly as a woman, is the narrowest of lanes. Most of our best—Cassandra Wilson comes most immediately to mind—moved away from “jazz” and “soul” to find an identity that allowed them to be artists. Others, such as Becca Stevens and Meshell Ndegeocello, made sure that they were never quite “jazz” to begin with. And even conventionally defined (and massively successful) jazz singers like Diana Krall have had to break boundaries to flex their individual creativity. Most recently, there is the example of Cecile McLorin Salvant, who might have been celebrated for decades as a “classic jazz singer” for a new generation but has consistently chosen to challenge those boundaries.

None of those outstanding artists has made music both more popular and more daring than Esperanza Spalding. Radio Music Society sits at the dead center of that conjunction. And, a decade later, it still sounds like the pure pleasure of revelation.