As the frontman for Talking Heads, David Byrne certainly earned a reputation as a critic of culture. Songs like “Once in a Lifetime” and “Burning Down the House” ask existential questions that poke at the dull monotony of the everyday. On the surface, Byrne’s only feature-length film, True Stories (1986), seems to follow suit.

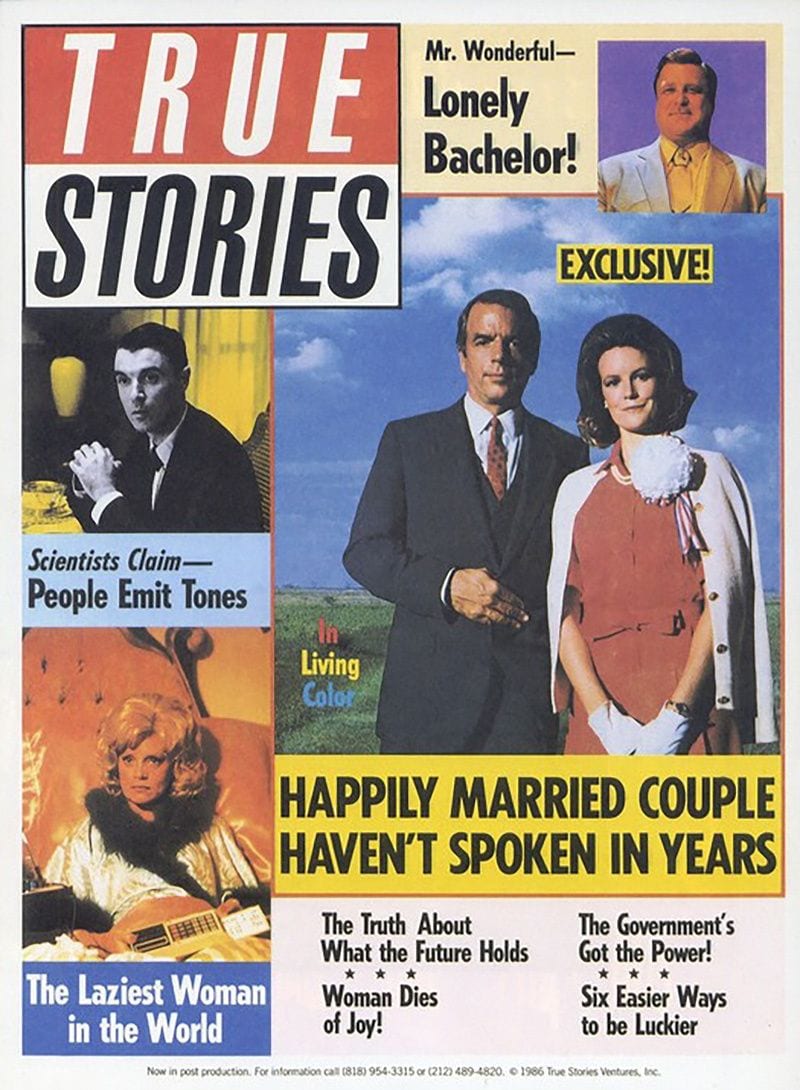

The characters are based on people featured in tabloid news stories that Byrne collected, later deciding to construct a narrative around their idiosyncrasies. The overlapping stories are situated in the fictional town of Virgil, Texas. We are introduced to the Lying Woman (Jo Harvey), the Cute Woman (Alix Elias), the Lazy Woman (Swoosie Kurtz), the couple who don’t speak to each other (Annie McEnroe and Spalding Gray), and Louis Fyne (John Goodman), the lonely bachelor who runs television ads in his efforts to find a wife.

As a piece of both cultural history and film history, True Stories takes its place alongside two other films from the mid-’80s that are also steeped in a surrealistic other-worldly place, Repo Man (1984) and Blue Velvet (1986). Virgil is celebrating what Byrne calls its “special-NESS”, with emphasis on the last syllable, as part of the Texas Sesquicentennial, marking 150 years of statehood. Virgil is also celebrating the transformation of a small town into a center of the growing semiconductor and computer industry, thanks to the presence of Varicorp, the corporation that evokes both Texas Instruments and Dell.

True Stories isn’t just about Texas. The film has a strong sense of place, yet it also speaks to its cultural moment: Reaganomics, the Cold War, and the beginning of both the Iran-Contra Affair and the savings and loan crisis of the ’80s. Two sequences in True Stories speak to these concerns. The first, evolving from the sermon by a televangelist and his multiethnic choir, is set to the song, “Puzzling Evidence”. After pointing to George H.W. Bush’s role as head of the CIA and asserting that “Texas is still paying for the Kennedy assassination,” the preacher (played by John Ingle), sings to his congregation: “Got your Gulf and Western and your MasterCard / Got what you wanted, lost what you had / I’m seeing / Puzzling evidence / Done hardened in your heart”. The scene places Texas at the center of conspiracy theories and intrigue of the ’80s.

Later, we encounter the Lazy Woman, who never gets out of bed but is perfectly coiffed and made up, watching television and offering a running monologue as she flips channels on her then-state-of-the-art remote. The scenes, focused on a bright full-color version of US capitalism, feature luxury products and home interior shots interspersed with clips of talking heads. The band members perform “Love for Sale” and appear in the mash-up of commercials, each dressed in a single, uniform color, almost forecasting the whimsy of Teletubbies, who premiered a decade later. Canned soda, Polaroid cameras, shavers, lipstick, syrup, toothpaste: the world of consumer pleasure is laid out in rapid succession. Overwhelmed, the Lazy Woman exclaims, “It’s great! They got that commercial attitude!”

Joe Nick Patoski, expert on all things Texas, explains how the Lone Star State tells a bigger story in “The Texas Connection”, one of the essays included with the Criterion Blu-ray: “This is very much a movie about America, as long as one understands that Texas is America on steroids — no one does suburban development, shopping as sport, religion as lifestyle, or blind optimism like Texans do. On the other hand, big hair, holy-roller preachers, the Kilgore College Rangerettes, and the one-eyed psychedelic accordionist known as El Parche couldn’t have come from anywhere else in America, and damn well sure couldn’t coexist anywhere but Texas.” If you’ve ever thought you might not fit in, fear not; Virgil will welcome you. While the portrayal of these characters is parodic, however, it’s never unkind.

Another special feature included in the new Criterion release is No Time to Look Back, a short film shot in 2017 by Bill and Turner Ross, self-proclaimed uber-fans of True Stories. The title is an homage to a scene in which Kay Culver, the wife of the mayor, hosts a fashion show at Virgil’s mall. The staging for the fashion show is interspersed with clips of Byrne walking through the mall, dressed in stereotypical Western garb that seems to indicate his desire to fit in with the rather typical mall crowd. From the podium, Culver calls out, “What time is it?” A beat later, Byrne, still walking, replies, “No time to look back.”

Nearly 30 years later, the Ross Brothers rephotographed locations of Byrne’s 1986 film, finding the same spots used in True Stories to see what may have changed. Rather than a sociological study, No Time to Look Back is a charming homage. The film includes a snippet from an interview with Byrne at the time True Stories was released. He says, “My hope is that it’s celebrating these ordinary people somehow,” adding that considered from a certain angle “they are just as sophisticated and avant garde as people from the city.” Byrne offers a perspective that he hopes audiences will also embrace, celebrating the special-ness not only of Virgil but also its residents.

In True Stories, Byrne is the intermediary between the audience and the people of Virgil, playing the stranger who comes to town with a naïve and charming incredulity. Because of the way he presents and interacts with the people of Virgil, the audience is able to see their quirkiness without judgment. We know we are simultaneously inside and outside of the film in the opening sequence when Byrne, standing on stage to narrate scenes of Virgil, turns and walks through the screen, if you will, and into the film.

Criterion’s Blu-ray case features a contentedly smiling, upside down photograph of John Goodman as Louis Fyne, who is essentially the protagonist of True Stories. His search for a wife is the story around which the others float, and the talent show that is the climax of the film features Louis’s performance of “People Like Us”. The lyrics epitomize Louis’ quest and tell a simple story about the people of Virgil: “We don’t want freedom. We don’t want justice. We just want someone to love.” For viewers coming to True Stories for the first time, Goodman is a familiar face from Roseanne, Raising Arizona, and The Big Lebowski. Criterion’s 2018 documentary The Making of True Stories tells the story of Goodman’s casting and Byrne’s almost oracular determination that this unknown young actor (he was 34) should play Louis Fyne.

The special features included in the Criterion package serve as an archive about True Stories. In addition to new essays written for Criterion, the four-color tabloid newspaper insert includes a small collection of Byrne’s photos and short essays from the 1986 book True Stories (David Byrne and William Eggleston III) along with Spalding Gray’s “The Obsessions of David Byrne”, first published in the October 1986 issue of Vogue. I’m likely not alone in reading Gray’s essay slowly and wistfully, with the same bittersweet feeling of watching him play the quirky and charismatic mayor of Virgil, Earl Culver. In the aftermath of Gray’s 2004 suicide, True Stories was an easier film to return to than the monologues of Swimming to Cambodia (Jonathan Demme, 1987) and Monster in a Box (Nick Broomfield, 1992) where his pain is so much more at the surface.

“The Obsessions of David Byrne” details Gray’s first meeting with Byrne, where the director showed him a drawing he’d made of Culver, that focuses on the mayor’s hands. The drawings showed a series of gestures Byrne had copied from a book on public speaking. “David went on to tell me that the character of Earl Culver had appropriated an unusually large number of these gestures and used them at random. They were almost like an abstract dance. Well, it all sounded good to me.” The result is Spalding Gray’s performance of a character who embodies Virgil: his gestures are nonsensical, but he’s so sincere about them, what he’s doing can’t possibly be wrong.

As the story of True Stories goes, Byrne wrote the songs for the album of the same name, released by Talking Heads. The songs performed by actors in the film are finally available on the soundtrack included in the Criterion release. Byrne is pleased to right this particular wrong, as he believes the songs belong to those characters. Hearing John Goodman sing “People Like Us” does indeed feel right, and there’s a joy in the neighborhood kids’ performance of “Hey Now”, the spirit of which Byrne’s vocals could not evoke.

More than 30 years after its theatrical release, True Stories remains delightfully weird. With hope, the Criterion release will add new fans to the film’s deserved cult status.