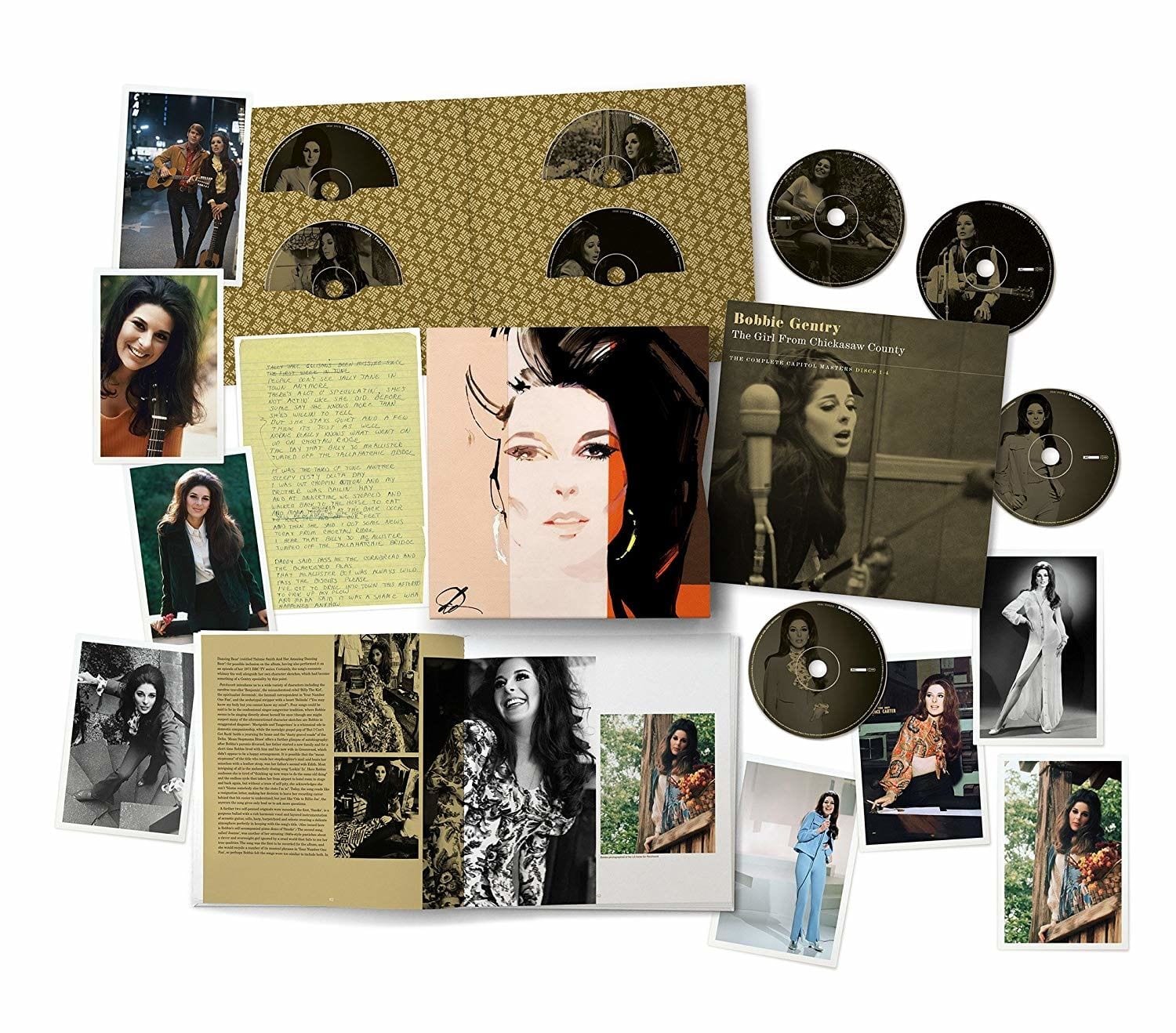

Of all the major label box sets issued last year, perhaps the one whose commercial and critical success most took the market by surprise was Universal’s The Girl From Chickasaw County, an eight-CD Bobbie Gentry package, rounding up everything the undervalued singer/songwriter recorded for Capitol, including a vast number of previously unreleased tracks. Why was its success a surprise? Well, despite her success as a writer, recording artist and live attraction, Gentry vanished from public life in the early 1980s. And it wasn’t a disingenuous vanishing, designed to bait the media. It was the real deal. No endless farewell tours. No nothing. Gentry hasn’t uttered one word to a journalist ever since.

Neither has Gentry participated in the revival of her catalogue which, prior to the intervention of reissue producer, Andrew Batt, had been allowed to lie fallow, notwithstanding a largely forgotten series of twofers produced by the Australian Raven label. Batt has a track record when it comes to successfully sparking worldwide interest in an underrated artist’s long-forgotten catalogue. Until 2010, Sandy Denny lagged far behind Island Records label-mates like Nick Drake in terms of catalogue sales, despite the fact that she had outsold him at the time they were originally recording. Then came Batt’s 19-CD box set of Denny’s work, so meticulously compiled and presented, it had the effect of completely reviving Denny’s ‘brand’. In its wake, he worked with Universal on deluxe reissues of the individual Denny titles, as well as further compilations, such as The Acoustic Sandy Denny, all of them successes.

In 2018, he sprinkled the same magic over Gentry. The fact that The Girl From Chickasaw County is now in its fourth re-press (practically unheard of in this age of dwindling physical sales and even more unusual when it comes to high-end boxed collections) speaks for itself. So do the high placings that the box achieved in all the prominent year-end lists. In addition to coming in at #8 in our own Best Reissues of 2018 listings, Gentry all but swept the board, with the following results: The Times (#1), The Los Angeles Times (#1), The New York Times (#1), Mojo (#1), The Boston Globe (#2), Shindig! (#2), Record Collector (#2), Variety (#3), Paste Magazine (#3), Billboard (#5), Rolling Stone (#5), The Sun (#8). It’s highly unlikely that many of these titles mentioned Gentry even fleetingly in the years prior to last.

Now, despite facing stiff competition in the form of luxury packages from the Beatles, John Lennon, the Doors, and Kate Bush, Gentry is in pole position in several world-class newspapers and music magazines. It’s an astonishing turn-around that speaks not only of the quality of her work but also of the efficacy of Batt’s approach to catalogue reissues; no corner-cutting, excellent sound quality/remastering, fully researched, literate notes and peerless presentation (in this instance, renowned illustrator, David Downton, was commissioned for a cover portrait of Gentry that dispensed with all the ‘country gal’ clichés an inferior artist would have surely been unable to resist). Soon, it will have sold out what may be its final print-run. So let’s hope that Universal strike while the iron’s hot and issue expanded editions of the individual albums or perhaps a vinyl series. Gentry’s the hottest she’s been in decades.

But still, the mystery is unsolved. Why did she walk away from public life? While no one claims to have the definitive answer, I spoke to four Gentry commentators to try to understand more about her life, her music career and her decision to call it quits; Andrew Batt (compiler/producer), Tara Martha (Gentry expert/author/journalist), Donald Bradburn (Gentry’s choreographer), and John Cameron (Musical Director for Gentry’s BBC shows).

Gentry’s background has an element of a rags-to-riches fairytale. She was born Roberta Lee Streeter in 1942, spending much of her childhood on her grandparents’ farm. The environment in Chickasaw County, Mississippi was one she would end up mining in great detail for her songwriting. Gentry taught herself piano by ear, picking out the chords of songs she heard on the radio (the farm had no electricity or plumbing, and her radio was battery-operated). In her teens, she joined her mother, Ruby Meyers, who had settled in Palm Springs, California. Meyers was a singer and she and Gentry formed a mother/daughter musical act. It was after high school graduation, however, that Gentry’s commitment to music took on a new seriousness. At the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music, her ability to play by ear was enhanced with traditional instruction in theory and composition, and she became fully musically literate.

When it happened, it all happened fast. Despite initially setting out to write songs for other singers, in 1967 she accepted a contract with Capitol Records. Her demos was so first-rate that some of them were used as official studio releases. In a stroke of good fortune, her first single “Mississippi Delta” was flipped and its reverse-side cut, “Ode to Billie Joe”, became the ‘A’. The rest is history. By summer of that year, Gentry had bagged a #1 with her very first release. In the UK, it was a respectable #13 and in Ireland a #6. “Ode to Billie Joe”, a song she’d initially intended to pitch to Lou Rawls, became one of those rare hits whose fame never dims, in part thanks to its storyline and unresolved mystery element. Just why did Billie Joe MacAllister jump from the Tallahatchie Bridge? And just what was it that he and his female companion threw into the river? Gentry set these compelling verses to a minimalist country-funk, guitar-accompanied melody that did away with the verse-chorus straitjacket of the pop song. The haunting Jimmie Haskell strings were the perfect finishing touch.

Gentry’s star ascended swiftly thanks not only to her musical talent, her instantly recognisable singing voice, with just a trace of grain and smoke in it, and her writing; she was also a TV natural. That’s how John Cameron first met her. The young arranger was on something of a roll, having arranged several international hits for Donovan, including “Sunshine Superman”. Cameron was immediately struck not only be Gentry’s glamor (“the music scene in the UK was still pretty low-key and parochial”) but also by her efficiency, polish and professionalism.

“On the back of a successful TV series with folk-singer, Julie Felix, and the arrangements for Donovan, I had been asked by director Stanley Dorfman, to handle the m.d-ing and arranging for the forthcoming Bobbie Gentry show,” he recalls. “She arrived with a stack of charts from her first album and I really learned a lot from them about writing sparse but memorable, funky string lines. I was working with a new string section on that show, led by Pat Halling, who had led the strings on the Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love” and they loved playing the parts.”

Cameron noted what a fast learner Gentry was. “And Stanley was a master at putting artists at ease in the studio. The formula was pretty relaxed, with special choreography worked out to Bobbie’s songs and some nice covers in the mix. The great thing about Bobbie was that she was in control – of her material, of her playing, how she wanted the songs to sound. The whole experience was one of great professionalism plus great style. And that voice! Hearing her sing “Morning Glory” or “Parchman Farm” while I conducted the orchestra was just one hell of a thrill for a tyro musician.” Cameron was impressed by both the woman and the talent. “She was warm, always upbeat, talented, musicianly. And a voice that sounded like Jack Daniels and honey poured over salted caramel ice cream. Bobbie was note- and timing-perfect. It never felt like she was in a studio – it was more like her front parlor.”

Andrew Batt, whose extraordinary commitment and dedication have powered Gentry’s revival, points out that by the time of her first single, she was already influencing other writers. “Dolly Parton’s ‘The Bridge’ seems a direct response to ‘Ode to Billie Joe’, with the same subject matter and location, even climaxing with someone throwing themselves off a bridge. In fact, Bobbie’s stark style and bleak subject matter influenced many of Dolly’s early classics, which are notably dark, like ‘Evening Shade’, ‘Down From Dover’, and ‘Gypsy, Joe & Me’.”

Batt first heard Gentry’s music via radio in the 1990s. “As soon as I started working in music, I knew that I wanted to do something with her catalogue if I ever got the chance. I got hold of the EMI tape report, so I knew there was a large cache of unissued recordings, meaning a full-scale project would be possible. I pitched my idea straight off the bat as Bobbie’s complete Capitol discography. I had some back-up ideas if they didn’t want to go ‘all out’, but actually from the get-go Universal were totally onboard with a box set. The project got approved very fast but still took a long time to come together.”

Batt’s fears that Universal might not want to go ‘all-out’ were not without grounds. Unfortunately, despite scoring a bestseller with her first album (also called Ode to Billie Joe), when Gentry fashioned an even better follow-up, The Delta Sweete, it failed to replicate its predecessor’s sales. Gentry would go on to experience successes interspersed with comparative failures throughout her album-making years. Prior to 2018, her stock wasn’t particularly high and some of the seven long-players she’d issued in a short space of time (1967-1971) had foundered in the marketplace.

There were also, says Batt, some crucial misunderstandings affecting how Gentry was seen by critics, casual music fans and label execs. “I think her glamorous appearance meant that in some quarters she wasn’t taken as seriously as she should have been – as if glamor could somehow negate intelligence! But it was a time when there was some expectation to look the part. If Bobbie had been wearing a smock, little makeup, and sat on a stool playing her guitar, her appearance would have coded her as ‘authentic’. Bobbie’s love of theatrical excess and her many TV appearances led her to be dismissed by some as a light-entertainment star with little to offer but that one big song. Certainly, one of the problems she had in her career was being perceived as too light for the singer/songwriter market and ultimately too esoteric for the mainstream.”

Falling between different stools is often the curse of the singer/songwriter. All of them, all the competent ones at least, are not confined to a genre. Those neat, artificial, restrictive little categories that seem to facilitate effective marketing don’t work for them. Gentry wasn’t country, yet she was. She wasn’t soul, yet she was. She wasn’t pop, yet she was. And so on. And when The Delta Sweete didn’t take off, it would take her another four albums or so to convince Capitol to let her write an album in its entirety. Her career is bookended by her finest achievements; the debut album, then The Delta Sweete and finally the album with which she bowed out, the exquisite Patchwork (1971). In between came compromises; some worthwhile but some, perhaps, to her detriment. She scored additional hits, both in her work duetting with Glen Campbell and with her own songwriting, bequeathing the world a second classic with 1969’s “Fancy”, a compelling, wry story-song about a poverty-stricken mother, determined that her daughter should find better circumstances using her wits and her beauty.

Along the way, some of Gentry’s input went uncredited. She herself was moved to comment on it when she spoke to After Dark in 1974: “There are no woman executives and no producers to speak of in the record business. I am a woman working for herself in a man’s field. I am a successful woman record-producer. Did you know that I took “Ode to Billie Joe” to Capitol, sold it and produced the album myself?.”

“Bobbie was perpetually robbed of proper credit as a producer both of her records and her BBC show,” says Tara Murtha, who adds that Gentry may also have found some aspects of the publicity machine rather wearing. “She had entertainment reporters pasting her image on to tabloid covers, promising sordid details of her personal life.” Gentry’s frustrations with the industry are, Murtha intimates, part of the reason she called it quits, ceasing to perform after 1980. “She was about 40 and had a kid when she retired. Given her experiences, why would she bother engaging in an industry that robbed her of credit?”

Murtha knows a thing or two, having first fallen for Gentry’s music when her husband introduced her to it. She was an immediate convert, later writing a perceptive and authoritative analysis of Gentry’s first album for the popular 33 1/3 series (Bobby Gentry’s Ode to Billie Joe, Bloomsbury, 2014). She relates to Gentry’s early drive to create. “I’ve been a workaholic and I understand the desire that drives that tendency. But one aspect of Bobbie people don’t seem to appreciate is how funny she was. She could be really heavy, writing poems about existential ennui and creepy ditties about being encased in glass, but she was also truly hilarious having armed guards ceremoniously present a pair of denim jeans with Tiffany diamonds for buttons at her Vegas show! Come on!”

Donald Bradburn’s experiences choreographing shows for Gentry left him with similar insights into her character. “I choreographed for Tina Louise, Barbara Eden, and Carol Lawrence, danced with Juliet Prowse, Debbie Reynolds, Shirley MacLaine, Goldie Hawn, and Barbra Streisand. They were all performers. Most relied on agents, business managers, personal managers, and lawyers to handle their business aspects. Bobbie was an independent, smart and savvy businesswoman. She was a perfectionist with an extremely strong work ethic. She was dedicated in rehearsals even when she was doing material she’d done for years. She would come to rehearsals early and practice by herself or with me, away from the other cast members. She was not dance-trained but she had steps and movements she was comfortable with and looked good doing. She designed her costumes and they were wonderful. She was great to collaborate with and open to so many new things. We did a new show every year from 1975 on and played the DI, the Frontier, Harrah’s in Reno and many other venues.”

Bradburn’s abiding impressions of her personality are all positive. He got to meet the person beneath the showbiz personality. “I knew I was finally a close enough friend when I got to go to her house and have her answer the door as Roberta Streeter, not Bobbie Gentry; no makeup, no shoes, wearing a kimono and standing much shorter in the doorway than her high-heeled stage and public persona.” He paints a picture of someone who, despite being able to summon an aura of grandeur as and when necessary, never became grand in the negative sense, never lofty or disdainful of others. “She was one of the world’s wealthiest women but she remained real.” Not only real but unfailingly generous to friends and colleagues. “Her opening night gifts to me started with a Piaget watch and later custom-designed sold gold belt buckles, bracelets, and other jewelry.”

Bradburn misses Gentry, who, it would seem, not only withdrew from the public, but also from the many professional friendships she had nurtured between 1967 and 1980. “Special moments? So many. Sitting with Elvis during the several shows when he came to see Bobbie. She and I also visited him in his penthouse suite at the Hilton. Visiting Liberace in his dressing room at Lake Tahoe and he showing Bobbie all his fur coats and robes. They tried on all the robes and put on a fashion show, laughing and twirling and giggling like two little kids at play. And going with her to the movies and to shows and out to dinner, just spending time with her and her friends, like Karen Harris and Stanley Dorfman.”

When Gentry’s Capitol contract was up for renewal, she was unable, on the back of the under-selling Patchwork, to strike a deal that valued her input as a songwriter and producer. In all likelihood it would have been more of the same; having to make compromises about song choices with a label that didn’t see her as the auteur and all-rounder she most certainly was; singer/songwriter/dancer/producer/guitarist/pianist. Instead, the company brass seemed to perceive her as a one-dimensional showbiz songbird.

Gentry moved on to Warners. By all accounts, there’s an an album’s worth of material in the vaults, but all that emerged was one single, 1978’s “Steal Away/He Did Me Wrong, But He Did It Right”. It would mark the end of Gentry’s recording career. Patchwork, which should have put her in just the right place to benefit from the singer/songwriter boom of the new decade, would remain her final album. It vies for the mantle of her best album with The Delta Sweete. For my tastes, it just nudges ahead, combining sparkling, Vaudevillian panache with impressive stylistic breadth, covering country, soul, gospel, blues, folk, Americana, and pop. Gentry’s dexterous (and uncredited) piano-playing helms some of the songs. Like Ode and Delta, many of its songs tell stories, from downtrodden, nostalgic “Beverley” to cheerful “Benjamin” and whimsical “Miss Clara”. Gentry skips through the proceedings with a wonderful lightness of touch, neither taking herself too seriously or not seriously enough.

As well as fictional narrative songs, Gentry also provides glimpses into her own life. And perhaps, Batt observes, Patchwork gives us clues as to what was going on for her at the time: “On Patchwork, there are four songs that could be said to be in the confessional singer/songwriter tradition,” says Batt. “Marigolds and Tangerines” is a whimsical ode to domestic companionship, while the gospel pop of “But I Can’t Get Back” holds a yearning for home and the “dusty gravel roads” of the Delta. “Mean Stepmama Blues” offers more autobiography; after Bobbie’s parents divorced, her father started a new family and for a short time Bobbie lived with him and his new wife in Greenwood, which didn’t appear to be a happy arrangement. It is possible that the ‘mean stepmama’ of the title, who reads her stepdaughter’s mail and beats her senseless with a leather strap, was her father’s second wife, Edith.

Most intriguing and poignant of all is the album’s closing track, “Lookin’ In”. Here, Bobbie confesses she is tired of “thinking up new ways to do the same old thing” but without a trace of self-pity. She acknowledges she can’t “blame somebody else for the state I’m in”. Today, the song reads like a resignation letter, making her decision to leave her recording career behind that bit easier to understand. But just like “Ode to Billie Joe”, the answers the song gives only lead us to more questions.”

More questions indeed. That’s for sure. Gentry hasn’t granted an interview since leaving public life in 1980. Her third marriage, to singer Jim Stafford, lasted from just 1978 to 1979 but gave her a son, Tyler. Journalists from around the world have attempted to disregard her privacy in the hope of landing the inside scoop about her ‘disappearance’, something both Batt and Murtha are steadfast in decrying. “I think she stopped performing for several reasons,” says Batt. “The chief of these was that without a new album to maintain public interest, she was increasingly becoming a nostalgia act and this would inevitably have meant playing smaller theatres with less lucrative contracts. It was better to go out while she was still somewhere near the top. In addition, Bobbie produced her shows via her own production company so, by the time she stopped performing, she was financially secure and could afford to retire comfortably. Thirdly, Bobbie wanted to have children. After the birth of her son, she wanted to make sure he would have a very different upbringing to her own. I don’t think she definitively decided to retire at the time of her last performance, but as time went by it made little sense to go back, especially as she had other business interests, including her music publishing and production companies. It’s been alleged that she continued to write for other artists under a pseudonym.”

Other details are scant, although Bobbie stepbrother, Bryan Holley, told Tara Murtha that when he visited her in 1984 she was working on a song-suite about the homeless. It’s unclear whether that project was intended for herself or for another artist, but it does indicate that Gentry continued composing beyond retirement. Perhaps one day, her vaults will open, but even if they don’t, The Girl From Chickasaw County is an exceptional artistic legacy; a vast body of work created within a mere four years. Gentry has finally been granted the unqualified praise and respect her many talents always merited.