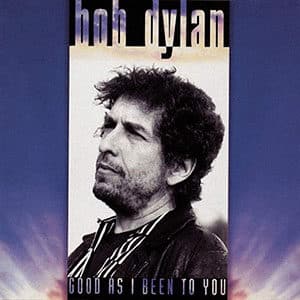

When Bob Dylan released his 28th studio album, Good as I Been to You in November 1992, it was exactly what his fans had not been waiting for. We wanted a ‘real’ Dylan album, not a grab-bag of dusty old folk songs.

Dylan had a terrible 1980s, a decade he spent stumbling from one debacle to another. He churned out a series of albums seemingly custom-designed to vie for the coveted ‘worst Bob Dylan album ever’ slot. He pulled a huge rabbit out of the hat at the very last minute in September 1989, the Daniel Lanois-assisted Oh Mercy easily outstripping any of his earlier ’80s albums. It was, as Dylan expert Michael Gray put it, a “confident staunching of the flow”. But the wound opened again with 1990’s Under the Red Sky, a slight, nursery rhyme-flavored set of songs that received worse reviews than tuberculosis. As it happens, the album was nowhere near as dire as critics made out, but it’s easy to see how it was a major disappointment in the wake of Oh Mercy: it has its charms, but even Under the Red Sky‘s best songs feel half-baked.

So it was only natural, if regrettable, that Good as I Been to You and its successor, World Gone Wrong, another acoustic covers collection, didn’t really receive the fairest of hearings. Even Oh Mercy, which many had interpreted as the start of yet another Dylan ‘comeback’, wasn’t really given its due. It’s an odd dichotomy: Oh Mercy built up high expectations that weren’t met, but in itself, it wasn’t quite appreciated enough at the time, given the strength of the songs, the performances, and yes, the way in which Lanois’s patented swampy production lent it a felicitous cohesion.

Good As I Been To You was warmly received by critics, but a Dylan album made up entirely of cover versions with a stripped-down, rough-edged acoustic aesthetic was not what was needed to satisfy a hunger for new Dylan material. Dylan’s detractors had him down as a washed-up old has-been, and long-term fans were finding it increasingly difficult to demur. Sure, his performances remained strong, and the song choices intriguing, but retreating to his garage studio in Malibu and tearing through an eccentric collection of mostly traditional, occasionally obscure covers was not going to do much to dent the gathering consensus that Dylan, as a songwriter, was a spent force.

Of course, we all know what happened next. Dylan’s reimmersion in what he has called his ‘lexicon’, that fathomless gestalt of folk, blues, and traditional song from which he drew so heavily during his formative years, allowed him to rejuvenate his musical inspiration, and eventually led to 1997’s career-resuscitating Time Out of Mind. Today, fully 25 years after that watershed album, Dylan can look back upon a late-career phase that has seen him become more critically lauded and more universally respected than in his ’60s heyday.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author David Remnick, in a long, surprisingly rote essay on Dylan published in the New Yorker last November, posited what he called his “A Unified Field Theory of Bob Dylan”:

The theory isn’t especially complicated or even novel. Greil Marcus has been pressing the case for years, and Dylan himself, always typed as ‘enigmatic’ and ‘elusive,’ has been trying to make these matters clear to us all along. In order to stave off creative exhaustion and intimations of mortality, Dylan has, over and over again, returned to what fed him in the first place—the vast tradition of American song.

To be fair to Remnick, he does admit that his ‘Unified Theory’ isn’t exactly ground-breaking. Indeed, as theories go, it’s about as far out on a limb as suggesting that getting roaring drunk tonight will lead to a hangover tomorrow. Still, clichés generally become clichés because they’re true. It’s customary in discussing Dylan’s path back to creative health in the ’90s, to quote his “Dylan Revisted” interview with David Gates at Newsweek in 1997:

Here’s the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else. Songs like ‘Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain’ or ‘I Saw the Light ‘- that’s my religion. I don’t adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I’ve learned more from the songs than I’ve learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs.

Has the story of Dylan reigniting his inspirational pilot light by reconnecting with the roots that nourished him during (and before) his early New York days been overplayed? Perhaps. But equally, it cannot be easily dismissed. Interestingly, he says, “I believe the songs” rather than “I believe in the songs.” One way to interpret that is to conclude that Dylan’s belief in this instance wasn’t a matter of faith, as it was with “the religious thing”. Instead, he believes what the songs tell him, and it’s these essential truths that provided the foundation upon which Dylan rebuilt his impetus to return to songwriting.

Hindsight allows us to view Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong in a completely different light. We can consider the albums on their terms, shrugging off the contemporaneous worry that they were mere contractual fillers, sideways steps intended to camouflage the writer’s block that Dylan had, not for the first time, been beset by. Many now regard World Gone Wrong more highly than Good as I Been to You. Dylan albums, particularly the better ones, tend to take a while – often years – to fully settle into their rightful place in the personal hierarchy of Dylan’s greatness. For me, the earlier covers album eclipses its successor, and I’m going to attempt here to explain why.

What’s so good about Good as I Been to You? For one thing, the song selection is wonderfully varied. Back in the day, people used to say the earlier album was made up of Folk covers, its successor of Blues. That’s reductive, but there’s no doubt that World Gone Wrong is more uniformly Blues-focused. In contrast, its predecessor showcases an eclectic miscellany of older, more traditional material – closer in spirit to that rich, strange heritage of “songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels”, as Dylan put it to Nat Hentoff in a 1966 Playboy interview.

Good as I Been to You breathes more easily than World Gone Wrong. It has more of a spring in its step and a wink in its eye. The performances occupy a more diverse tonal range. They’re multi-dimensional. They bite deeper. Somehow, despite the variety, the album’s various shades of lovelorn regret, shot through with sudden violence, hard liquor, thick smoke, and sympathy for the underdog, coalesce into a more unified whole. What English literary critic Robert McCrum said of Dylan’s 1962 performance of “The Ballad of the Gliding Swan” in The Guardian in 2005 could just as well be applied to the songs on this album, recorded fully three decades later: “The instinctive juxtaposition of savagery and tenderness, the extraordinary marriage of material, ancient and modern, articulated in that feral note of self-laceration have always been keys to Dylan’s art.”

“Frankie and Albert”, the propulsive opening track, is worth the price of admission. Had it been included on one of Dylan’s more artistically impoverished ’80s albums – Down in the Groove, say – it would have stuck out similarly to how “Brownsville Girl” offers a beacon of light amongst the stultifying murk of Knocked Out Loaded. Dylan launches into the song in a way that, in today’s parlance, we might call ‘leaning in’. From there, he skips hither and yon across genres and song styles, all the way through to album-closer “Froggie Went A-Courtin”, turning in a series of bravura performances which, taken together, represent his most satisfying and important album since Street-Legal. Contrary to received wisdom, this actually is a ‘real Bob Dylan album’. It just didn’t reveal itself as such at the time.

Dylan’s cadences and phrasings are a constant delight. Take, for example, the uncanny knack he has for spinning seemingly mundane phrases into pure vocal gold by applying almost onomatopoeic inflections: the way he stretches out the word ‘long’ in “won’t be gone too loooooooooong” in “Frankie and Albert” so as to render it all the more rueful; how he rescues the word ‘honey’ from cliché in “Black Jack Davey”, the vowels stretching and bending like a clear viscous dollop dripping from a spoon; his variation of the phrase “Put me outta doors” in “You’re Gonna Quit Me”, each time more supple and lingering than the last, the vocal so clear and upfront you can almost feel the rasp of his stubble; how rhythmically he enunciates the internal rhymes in “Jim Jones”: “they’ll yet regret”, “take a trip before you ship”, “Don’t get too gay in Botany Bay”. These are mere surface flourishes, white caps on the choppy surface of an album that rolls deeper than anything Dylan had given us in a very long time.

What’s interesting – and, to some, irksome – is that many of Dylan’s versions of these songs are not his new arrangements but, in fact, are patterned quite closely on specific renditions by other artists. “Jim Jones”, in particular, is Dylan’s version of Mick Slocum’s arrangement for the Australian folk group the Bushwhackers. Credit must be given to Slocum for the arrangement (something Dylan initially failed to do, triggering a lawsuit). Listening to that Bushwackers version now, in light of Dylan’s, it feels archaic, mannered, and so slow as to be practically somnambulant.

Belied by Dylan’s spritely delivery, the story “Jim Jones” tells is unremittingly grim. This is no jolly sea shanty. A first-person poacher’s tale of deportation from England to Australia, it roils with vein-popping anger at systemic inequality, routine injustice, and institutionalized cruelty. As Gray puts in, in his long, meticulous chapter on the acoustic albums in Song & Dance Man III (1972), “In evoking such desolation by vocal caress as well as by stark and wayward strain, Dylan fully inhabits the song’s world of a savage penal code in the old land, and of exile across a huge sea to further chains and cruelty, scrubland and thwarted desire”.

Inhabiting the song and the subject, Dylan pulls us in too. We can practically feel the skin-shredding rub of the chains, the briny sting of the rolling ocean, and the terrified despair of exile. As the narrative progresses, the emotional intensity ratchets, tracing an unwilling journey from home forever into a harsh new foreign world of pain. There are verses here that carry a pang as sharp as standing too close to a fire and feeling seared by the flames:

Now it’s day and night the irons clang

And like poor galley slaves

We toil and toil, and when we die

Must fill dishonored graves

There’s poignant irony in the contrast between the story’s horror – men convicted of petty crimes condemned to face torture and hard labour culminating in lonely, unjust early death – and the sheer enjoyment of the song, as performed by Dylan. Dylan’s languid vocal beguiles in so many ways, cadences stretching and compressing, words skidding across the surface of his deft guitar lines.

You might be forgiven for assuming that at least the hardcore folkies would have been in raptures over Dylan’s first fully acoustic album since Another Side of Bob Dylan in 1964. This album’s harshest criticism came not from the mainstream but from the most assiduous carriers of the folk flame. Folk Roots magazine called it “crap”, his singing “truly dreadful”. Lambasting Dylan as a “rich old has-been”, their review signed off by calling him a “played-out, talent-fucked bastard!” Come on, Folk Roots: get off the fence!

In truth, the objections were not really inspired by Dylan’s performances. Rather, it was his cavalier habit of having his record label tag every song as “Traditional, arranged by Bob Dylan”, even though, as noted earlier, Dylan’s versions of these songs are often remakes of other people’s arrangements. One of the most obvious was Dylan’s “Canadee-I-O”, which he had clearly taken from English folk traditionalist Nic Jones, whose album Penguin Eggs opens with a crystalline version of this ‘trouser song’: the story of a woman cosplaying as a sailor to slough off the gender politics of her times and join a boat trip to Canada.

A counterpoint to “Jim Jones”, “Canadee-I-O” sees its protagonist undertaking a boat trip against the will of everyone else on board. In some ways recalling the narrative ambiguity of Blood on the Tracks songs such as “Tangled Up in Blue”, this seemingly third-person narrative eventually resolves into the first person, as the narrator turns out to be the protagonist, a twist ending that is easily missed. There’s also a striking dubiety in the song’s message, which basically says: the most unlikely good fortune saved me from a horrible fate, and therefore you should go right ahead and rely on it happening to you too.

Dylan’s guitar playing cannot compete with Jones’ meticulousness, nor do his rough-hewn vocals come anywhere near Jones’ immaculate singing. However, if you value Dylan for his emotional intensity, you’re bound to be seduced by his rendering of “Canadee-I-O”. Lyric after lyric is plucked free of mundanity by dint of Dylan’s inflections. He can squeeze more emotion out of one phrase than most singers can get into an entire song. Recurring words and end lines – “true”, “blue”, “rage”, “engage” – accrue more significance with every subtly different vocalization.

Dylan’s version of “Arthur McBride” relies heavily on that of ex-Planxty singer Paul Brady, a man so admired by Dylan that he called him a ‘secret hero’ in the liner notes to 1985’s Biograph. Dylan hews closely to Brady’s canonical recording of “Arthur McBride”, again making his version of somebody else’s version of a song his own. Even so, this and Nic Jones’s “Canadee-I-O” are the two Dylan facsimiles that most struggle to transcend their models. Inevitably, Brady’s guitar work comfortably surpasses Dylan’s in terms of technical ability, his nimble playing way beyond what Dylan aims for. Nonetheless, Dylan’s wayward guitar flailings carry more emotional weight than any note-perfect display of virtuoso picking.

Good As I Been to You was widely criticized not only for Dylan’s allegedly slapdash guitar playing (though one man’s slapdash may be another’s sublime), but also for his nasal, pinched vocal tone. It’s true that during the early to mid-’90s, Dylan’s singing hit peak adenoid, but if you’re the kind of Dylan fan who objects to nasal singing, you probably go to boxing matches and protest that they’re too pugilistic.

Moments do arise, though, where he skirts dangerously close to self-parody. As sung by Dylan, the ‘show’ in the dainty phrase “cuts a gallant show” in “Canadee-I-O” comes across more like “shaw”. Rather than dilute the expressiveness, this somehow manages to enhance it. The song’s intensity builds throughout, the penultimate verse, in particular, likely to raise goosebumps for anyone at all receptive to Dylan’s art:

Now, when they come down to Canada

Scarcely ’bout half a year,

She’s married this bold captain

Who called her his dear.

She’s dressed in silks and satins now,

She cuts a gallant show,

Finest of the ladies

Down Canadee-i-o

Purity of tone may not be a key feature of Dylan’s singing, but he certainly doesn’t lack ambition in the range he’s willing to attempt. His sinuous, tight-rope walk of a vocal on “Tomorrow Night”, a song best known from Elvis’ version, wobbles but doesn’t ever quite topple over. In retrospect, the Lounge Bar aesthetics prefigure Dylan’s forays into crooning on “Moonlight” on Love and Theft, not to mention the several discs of Sinatra-venerating ‘American Songbook’ covers.

World Gone Wrong is more uniform in quality than Good as I Been to You. Stand-out tracks are easier to identify on the earlier album. There’s no filler, no fat at all, but there are a couple of noticeably less effective performances. “Sitting on Top of the World” and “Little Maggie” are both relatively perfunctory and, coming together in the running order, represent the closest thing to a lull on the album. “Sitting on Top of the World” features a vocal that seems cramped and tentative. “Little Maggie”, the only song Dylan performed during his Never Ending Tour shows to make it onto the album, is no more than a palate cleanser among the album’s more accomplished performances. Like its subject, though, it still packs a punch. The plot traces that classic triangle of unrequited love: the narrator yearns for the eponymous Maggie, who longs for another man.

“Hard Times”, on the other hand, is unquestionably one of the best songs on either album. It cuts to the bone. Dylan’s voice attains an unrivaled intensity here, investing the refrain with every ounce of emotional charge at his disposal. It’s a completely straight, irony-free rendition. No winking or nodding here; instead, it’s an impassioned plea for what Thomas Pynchon called the ‘preterite’: the lost, forgotten, passed-over poor souls of the world. Melodically beautiful guitar lines alternate with the vocal’s howl into the void in protest at proletarian life’s vicissitudes.

Flecked with anger yet buoyed by camaraderie and fellow feeling, this is a performance to stand up against, say, “Moonshiner” or “He Was a Friend of Mine”. Yes, Dylan’s voice is aged and weathered, but what it’s lost in elasticity, is gained in texture and gravitas. Its fissured, rebarbative beauty calls to mind Flaubert’s famous aphorism on the futility of words: “Human language is the cracked kettle on which we beat out tunes for bears to dance to, when all the while we long to move the stars to pity.”

Gray notes this 19th Century ballad, like a number of the album’s songs, is self-reflexive, a “song-within-a-song”. Shining light upon the unexamined lives of the poor, the song highlights how “oppression too can seem like a creature that might be creeping under the door”. For Gray, these songs “turn a radio telescope upon the past, retrieving that which seems light-years away in the era of Microsoft, McDonald’s, and MTV. These albums are anthologies of individualism, but they also champion the dignity of labour, the silenced and oppressed.” Immersed in the world conjured by Good as I Been to You, the listener could be inside a Walker Evans photograph or watching Robert Crumb’s ‘A Short History of America’ sequence played in reverse.

Dark themes don’t infuse every song on Good As I Been to You. “Step it Up and Go” (side two, track one, in the olden days of vinyl) is a joyous, rambunctious frolic. “Diamond Joe” is a jaunty, humorous tale of hard graft and exploitation, a happy song about a miserable experience. “Frankie and Albert” may be tragic, but Dylan manages to get a smile out of us by the way he sings of the fatal .44 pistol going off “a rooty-toot-toot”.

The final track, “Froggie Went A-Courtin”, the oldest song here, was originally a nursery rhyme, said to have originated as a satire on the byzantine shenanigans at the 16th Century court of England’s Elizabeth I. Billed sometimes as “A Moste Strange Weddinge of the Frogge and the Mouse”, the song appears (as do others on the album) on Harry Smith’s seminal Anthology of American Folk Music, Smith’s idiosyncratic liner notes in their upper case, news headline aping style summarizing it thus: “ZOOLOGIC MISCEGENY ACHIEVED IN MOUSE FROG NUPTIALS, RELATIVES APPROVE”. Dylan braids a wholly serious performance with the ostensibly comedic material to produce a unique version of a centuries-old song, signing off the album with the puckish valediction “If you want any more, you can sing it yourself, Uh-huh.”

Many of these songs, being traditional and thus performed countless times over so many years, exist in variants. Attempts to trace their history, their versions and mutations, and familial interconnections with other songs would rapidly overrun the scope of this article. Folk and Blues songs are dense with motifs and themes. Lyric phrases are pilfered and cannibalized. Plots and characters migrate from one song, or even song form, to another, leaving a trail of echoing resonances. These tangled interconnections and almost incestuous interminglings call to mind Pynchon’s inimitable description of a particularly rich and variegated topsoil: “a stringing of rings and chains in nets only God can tell the meshes of”.

World Gone Wrong aside, there’s no other ’90s record remotely resembling Good as I Been to You. Its closest kin may be Kristin Hersh’s sublime 1994 album Hips and Makers, which, like Dylan’s, strikes sparks off the touchstone of Smith’s ‘Anthology’, a collection that in October 2020, New Yorker writer Amanda Petrusich called “a dizzying catalogue of human experience” beloved for “what they indicate about an America long obliterated” and, crucially, “a work that unlocks other works”. It’s worth noting that while Dylan’s borrowings may seem presumptuous or inconsiderate, they at least nudge open trapdoors into other artists’ catalogues. How many of us would otherwise have found our way to Nic Jones’ Penguin Eggs (1980) had Dylan’s magpie ear not alighted upon it?

Gray notes how these songs “celebrate oral history, working-class history, history that struggled across oceans”. Kristin Hersh, in praising the authenticity of Folk songs, talked of “music that was written by no one, which is key to understanding what music really is. I love the faceless definition of true Folk, which is a song that’s probably Celtic in origin, carried across the sea, and altered by all the voices who sang it. The same with Blues songs, which changed as they walked from town to town.” Play Hersh’s Hips and Makers back to back with Good as I Been to You and you can hear two great artists, coming from different angles and backgrounds, connecting and communing with that same rich heritage. Hersh’s album ends with the title track, its opening phrase connoting the watery odysseys common to these songs and their complex and interconnected histories: “Rocking on the ocean, Sucking up the sea”. Her closing line offers the assurance that “Finally it’s alright. It’s alright.” Don’t give up hope. Believe the songs.

These tracks are haunted by the ghosts of Dylan’s songs, past – and future. In the day, waiting for Dylan to produce a new album became an increasingly forlorn experience, given his seeming inactivity and the assumption that time was running out. Nobody then knew that, all these years later, Dylan would still be going, still releasing albums, still touring (despite vertigo), still heading for another joint.

Time is a funny old business, particularly when it comes to the Bard of Minnesota. As I reacquainted myself with this album in 2022, I could not help but be struck by the fact that what was once seen as a desperate, late-career contract-filler is now revealed as only a halfway marker (so far) in Dylan’s long, storied career: 30 years separated Good as I Been to You from Dylan’s debut album; the same number of years separated it from my 2022 reimmersion. The year 2022 marked the quarter-century anniversary of Time Out of Mind; an expansive Bootleg Series box set, Fragments, is released in January 2023. How Bloomsbury’s 33.3 series of album monographs missed the trick of publishing an entry on Time Out of Mind on this anniversary is anyone’s guess.

We’ll return to the question of time when Fragments is released. For now, let’s indulge in just one small sidebar: in his pungent, gnomically poetic liner notes to World Gone Wrong, Dylan speaks of “learning to go forward by turning back the clock, stopping the mind from thinking in hours, firing a few random shots at the face of time.” Time Out of Mind can be viewed as a song cycle, performing an endless, Möbius strip-like loop, its final song wrapping back onto its opening track. (It’s a similar trick to the one Dylan pulled on 1967’s John Wesley Harding, where the final verse of “All Along the Watchtower” chronologically precedes the song’s opening.) Consider how the opener, “Love Sick”, and the final song, “Highlands”, both find Dylan walking, alienated, tormented by the easeful lives of others – “lovers in the meadow”, “silhouettes in the window”, “people in the park, forgettin’ their troubles and woes”. In “Love Sick”, Dylan hears “the clock tick”; in “Highlands”, he says he wishes “someone would come and push back the clock for me”.

Running out of time. Wishing to return to the past, to turn back the clock. Dylan might have experienced such feelings in his home studio when he recorded the songs that would make up Good as I Been to You. His fans could have been forgiven for feeling the same way. Dylan made these old songs new, made them his own. These are Dylan songs. His performances bring out the grain in them, limning their rich, expressive details like oblique light shafts illuminating the faint downy hairs on a woman’s arm. As with everything Dylan does, even when others have done it a hundred times, and many have done it very well, he somehow does it differently – and often best.

All these years later, with the hindsight of Dylan’s successes since, we can relax and enjoy Good As I Been to You for what it is. It’s an album that reaches great artistic heights by stooping to embrace the underdog. As Dylan scholar Andy Muir has written, Dylan’s “intuitive understanding and love of the songs” gives them such emotional impact. Dylan’s passion for the ‘lexicon’ bleeds into his performances. We don’t just hear these songs, we feel them. Taking refuge in the past allowed Dylan to find a path to the future: scrolling backward to move forwards. Balancing humility with defiance, anger with tenderness, Good As I Been to You longs to move the stars to pity. It cuts a gallant show.