“Strangers When We Meet” – Outside (1995)

Here’s another overlooked beauty from the otherwise clattery cacophony of 1995’s Outside. Reteaming with Brian Eno, Outside attempts to reinvent Bowie as an industrial, techno-rock artist, and while it all sounds ambitious, it is, at an hour and 15 minutes long, quite a slog, which means many listeners never gave song #19 (!) much of a listen. Too bad, as it’s easily one of his best songs of the ’90s. A holdover from the Buddha of Suburbia project and re-recorded for Outside, the song is built on a simple 4–3 bassline, and the rhythm section keep their heads down as Mike Garson’s lovely, inventive piano flourishes provide embroidery. But nothing gets in the way of Bowie’s excellent, and largely untreated, vocal performance, one of his best. It’s a refreshing piece of subtlety on a dense album.

“Little Wonder” – Earthling (1997)

The most fascinating thing about “Little Wonder” is the clash between the frenzied jungle electronica and Bowie’s simple, relaxed vocal and melody. Electronic bands like The Prodigy and Daft Punk had big hits in ’97, and Bowie, at age 50, took one last shot at keeping up with what the kids were doing. In addition, Oasis was coming off of its biggest hits, and the guitar drive and Bowie’s decidedly pronounced British accent recall that band as well. There’s some classic Bowie schizophrenia here, splitting the drum ‘n’ bass of the verses with the thick guitar rock of the “so far away” chorus. The lyrics are scattershot nonsense, working in all the names of the Seven Dwarfs, and Bowie settles for winks and nods at his own image in lines like “Mars happy nation / Sit on my karma / Dame meditation / Take me away.” Tin Machine cohort Reeves Gabrels is a miserable influence on Earthling and continually overwhelms the album with his guitar sludge. Still, “Little Wonder” is a clear highlight.

“Something in the Air” – hours… (1999)

After the sonic maulings of Outside and Earthling, the comparatively straightforward hours… came as a welcome end of the decade for Bowie. Not that the songs were there, exactly. Reeves Gabrels is still in the way, for starters, and his production and guitars remain a liability. One that got away was “Something in the Air”, a moody, artful, understated breakup song, a chronicle of a couple that has finally decided to hang it up, and thankfully he might be talking about himself and Reeves. Bowie uses another new voice here, that of the exhausted, defeated character who admits, “I’ve danced with you too long.” Bowie sounds bleary and sings with a staggering pace and foggy tone, and when he holds notes on the chorus, he lets his voice droop flat as though he can’t muster the will to go through with the breakup. “Can’t believe I’m asking you to go,” he sings, before his distorted vocals mix with squealing guitars to sound like pure anguish.

“Heathen (The Rays)” – Heathen (2002)

Fans and critics alike have applied the phrase “best album since Scary Monsters” to every Bowie LP of the last three decades, but with Heathen, it was actually true. It isn’t a perfect album, but the return of producer Tony Visconti made for obvious improvements, bringing about a return to a more focused, relaxed compositional and sonic gracefulness. The record is bookended by the hushed spiritual meditations “Sunday” and “Heathen (The Rays)”. The latter is a stunner, a richly arranged blend of guitars, synths, Phil Spector drums, and Bowie’s careful, pensive vocals.

Heathen is a commentary on Man’s state of belief or lack thereof, another step in Bowie’s lifelong journey through gnosticism, Christianity, Buddhism, the occult, Nietzsche, Aleister Crowley, and more. “Heathen”, the song, evokes 9–11 (“steel on the skyline/sky made of glass”), life’s inevitable sunset, and the possibility that none of our lifelong questions will ever be answered. There’s no chorus, and all three verses have a different chord progression, as Bowie finds cripplying beautiful notes to sing. Bowie’s real artistic rebirth starts here.

“Never Get Old” – Reality (2003)

Heathen proved that Bowie could finally stop both forging the musical future or trying to keep up with current trends. Thankfully, Reality continues that course, again with producer Tony Visconti, even though it rocks harder than Heathen and has none of Heathen‘s cohesive design. At age 56, Bowie proclaims that he’s never going to get old on the album’s third track, and the song’s quasi-disco groove and some of Bowie’s most lively singing in years seem to support his claim. Bowie, naturally, claimed that the lyrics were ironic, just like the terrible album cover of an anime Bowie that shaves 30 years off of him. That’s the joke — Bowie is sending up artists his own age who are desperate to keep it rolling with the drugs, the money, the women. Bowie was presumably trying to distance himself from such vanity, but this is Bowie, so the lines between irony and sincerity are blurred. “I’m never ever gonna get old,” Bowie sang. And he never will.

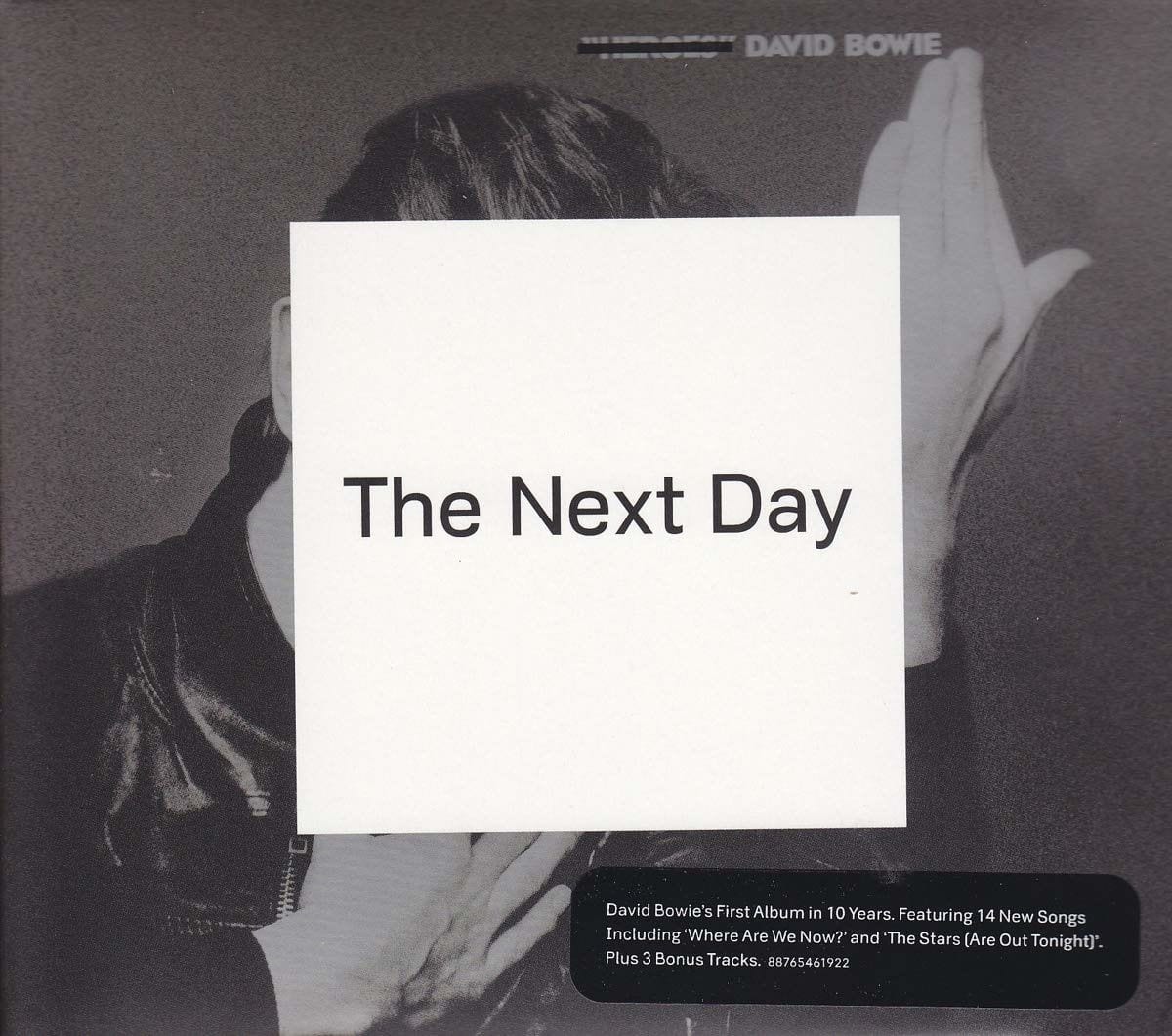

“You Feel So Lonely You Could Die” – The Next Day (2013)

After Bowie’s heart attack in 2004 on the Reality tour, he withdrew from recording, touring, and public life in general. For a decade, Reality was assumed to be Bowie’s final album. And then, in 2013, with no advance publicity, Bowie surprised everyone with The Next Day. “Here I am, not quite dying,” sings Bowie on the album’s lacerating title cut, and Bowie did sounds thrillingly alive on his comeback, a record at turns blisteringly melodic and defiantly fierce. “Where Are We Now?” is the timeless classic, with Bowie once again sitting in a tin can, this time a train in Germany, and finding an exquisite elemental compromise in order to cope — clinging to sun, rain, fire, and our fragile investment in each other.

And on “You Feel So Lonely You Could Die”, Bowie tweaks a Hank Williams title and writes one last great waltz. This is no love song, however, but one of the bitterest, most vindictive songs Bowie ever wrote, a seething forewarning to a traitor. It’s an amazing arrangement from Tony Visconti and an evocative performance from Bowie as he proclaims his cold war. The drumbeat at the end is an obvious reference to “Five Years” all those years ago.

“I Can’t Give Everything Away” – Blackstar (2016)

The last song from the last Bowie album: “I know something is very wrong / The pulse returns for prodigal sons / The blackout’s hearts with flowered news / With skull designs upon my shoes.” For decades, his fans looked to Bowie for how to live — his intellectual curiosity, his artistic audacity, his nonconformity, his personal style. At the end, he showed us how to die — with grace, courage, and a blaze of glory. Blackstar is a triumph. As his first #1 album in America, there won’t be many deep cuts here, and “I Can’t Give Everything Away” is already a fan favorite. But the song — with its blue-bayou melody, the stealthy lyricism, the eloquence in Bowie’s voice, that gorgeous 12-count wait before the refrain resolves, Donny McCaslin’s saxophone streams — is a fitting way to end a career from a man who until the very end gave us everything.

This article was originally published on 31 January 2016.

- David Bowie: Young Americans

- David Bowie: The Next Day

- David Bowie: The Buddha of Suburbia

- The Great I Am: Magic, Fascism, and Race in David Bowie's 'Blackstar'

- Counterbalance No. 16: David Bowie - 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars'

- David Bowie: ChangesNowBowie

- 'What a Fantastic Death Abyss': David Bowie's 'Outside' at 25