Olivia ‘Physical’ — The Video Album

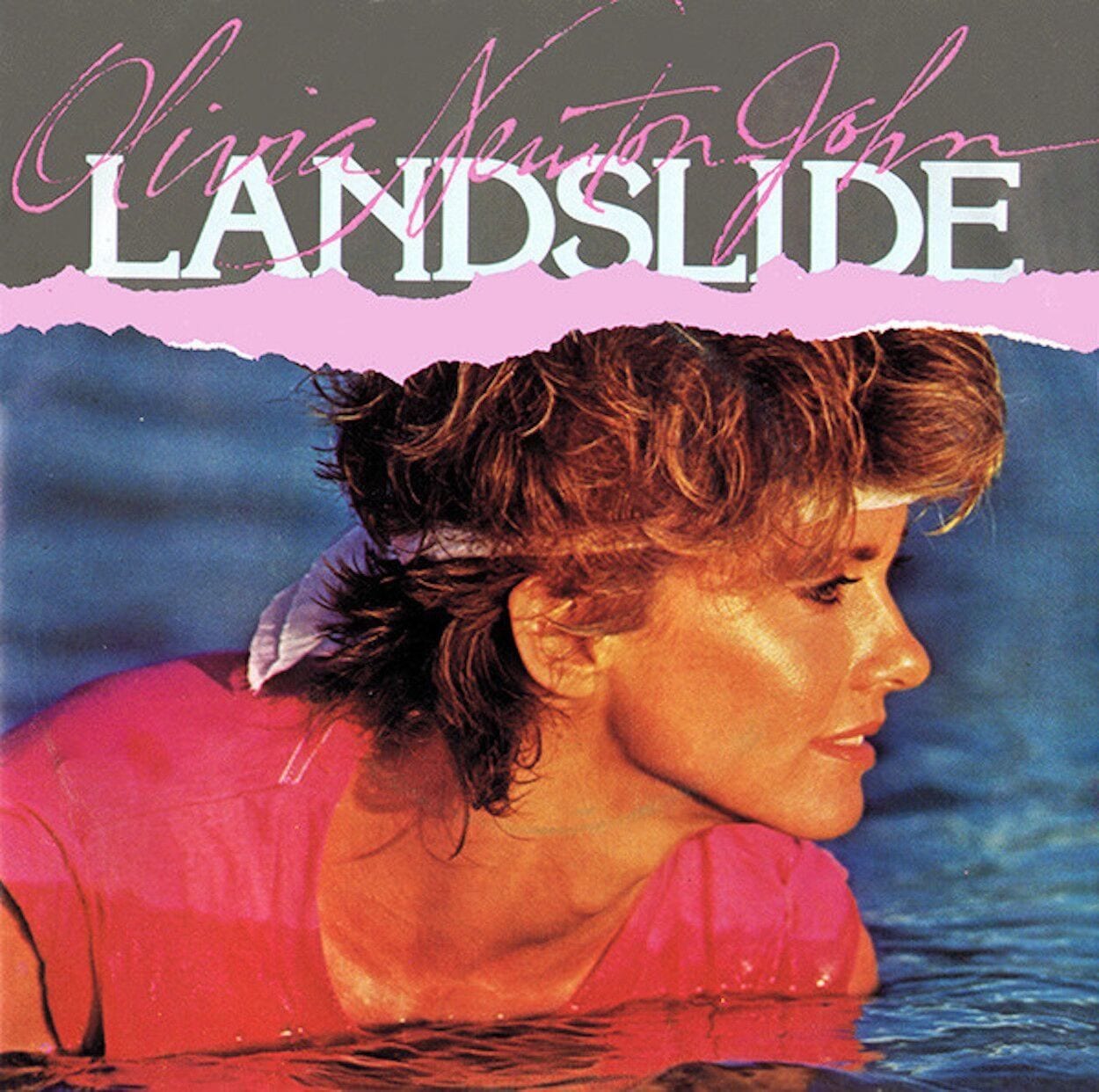

MCA Records packaged Physical in a striking sleeve photographed by Herb Ritts. With her face tilted towards the sun, Newton-John projected health and vitality. Filmmaker Brian Grant was among the first people to see what became a defining image of the singer’s career.

During the summer of 1981, Roger Davies’ office flew the London-based director to Los Angeles as a possible candidate to shoot videos for Physical. “I was taken to Olivia’s home in Malibu,” Grant recalls. “She invited me in. She was very lovely. She and Roger, and a guy from the record company, were actually choosing a photograph to use for the album sleeve. They set up a projector in her bedroom, of all places. She said, ‘Come in here. We’re just looking at some slides and photographs of pictures for the album cover.’ I sat down with her and Roger on the bed looking at these slides. Then we started talking about ideas, and what I thought of the album, and all the rest of it.

“I was there for about an hour-and-a-half. As I was walking out of this lovely house, having had this lovely conversation with Olivia, I sort of thought, I’m never going to see her again because I’m never going to get this gig. When I got to the door, I shook her hand, and I said, ‘It’s been absolutely delightful to meet you. I can now go home and tell all my friends I sat on Olivia Newton-John’s bed with her.’ That was the end of it. A few weeks went by and I then got a call saying that I got this gig. Olivia later told me that she’d met a whole pile of other directors and none of them made her laugh … but I did and that’s why she chose me.”

Months before MTV launched in August 1981, Davies and Newton-John had actually decided to make a full-length video ofPhysical. “The technology that mattered at that point was LaserDisc,” Grant says. “Roger had the idea that if we filmed every track on the album, we could put it out on LaserDisc, which is another piece of product that they could sell. If there were subsequent singles released, they’d already have the video.”

Prior to 1981, video clips occasionally appeared on television programs but were mainly used for in-store promotions. “One of the reasons record companies commissioned very cheap music videos in those early days was actually to play them in record shops,” Grant continues. “I started making them in 1979, having seen ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ (1975) from Queen. There were about five or six directors in London making these clips that were mainly used on Saturday morning children’s shows and occasionally on Top of the Pops.” Newton-John had filmed three such videos for Totally Hot, but an entire album of conceptual videos was still uncharted territory.

In fact, Blondie was the very first act to release a full-length video album for retail when David Mallet, one of Grant’s partners in MGMM Productions, directed the band in 12 clips for their fourth LP Eat to the Beat (1979). However, Chrysalis Records had begun the project solely as a promotional tool before it quickly evolved into a product. “Although Blondie’s video version of Eat to the Beat can justifiably claim to be the first video album, legal negotiations with the musicians union kept it from staking that claim in the marketplace,” Billboard stated in November 1980, shortly after the video’s release.

A year later, MCA Videodisc president Jim Fielder appeared at Billboard‘s third international video entertainment/music conference where he called Olivia Physical “the first musical album to be conceived for both audio and video formats from pre-production on” (19 December 1981). Fielder’s claim might seem misleading based on the chronology of Blondie and Newton-John’s respective projects, but his qualifying distinction — “from pre-production on” — is tellingly accurate where budgets and marketing are concerned. As reported in Billboard, Eat to the Beat cost $140,000. By comparison, MCA granted a whopping $800,000 for Olivia Physical.

Grant had a large sandbox to play in. Producer Scott Millaney and writer Marcelo Anciano joined him in Los Angeles where they began developing ideas for each song. “They stuck me and Marcelo in a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont,” Grant recalls. “We went into two separate rooms. For two weeks, we threw ideas backwards and forwards between us until we came up with an idea and a solution for every single track. At that point, music videos were little laboratories. I always say the record business paid for my film school because the joy of it all at that time was that nobody knew anything. There was no library. There was no YouTube. There was no Internet. The only influences were photography and movies. Everybody was experimenting.”

While tracks like “Carried Away” and “Falling” translated to sparsely designed sets, and “The Promise” simply incorporated pre-existing footage of Newton-John with dolphins, “Recovery” was shot on location in the Mojave Desert. Throughout the clip, the singer encounters hidden tree-trunk mirrors, oversized tumbling dice, and a cage of tuxedoed suitors before arriving in a dusty saloon populated by clones.

Grant explains, “We came up with the conceit that [spoiler alert!] what you find out is that she’s in a room with a psychiatrist, so all the imagery comes out of that session. If you look at it carefully, there’s a big pencil, and then you suddenly cut to a face, and there’s somebody tapping their lips with a pencil, who turns out to be the psychiatrist.”

“Silvery Rain” featured more unnerving kinds of imagery. “It’s about ecology; it’s about acid rain, so Marcelo and I thought about lots of visual ways of illuminating those ideas,” Grant says. “It was a question of trying to do that in an abstract form. If you look, Olivia’s actually standing in a giant hand. The dome is meant to represent how the world is now open to all of these terrible things happening to it.” Using surreal visuals to forecast the impact of pollution and acid rain, Grant’s video is a powerfully disturbing companion to the song.

Though “Landslide” had all the trimmings of a big-budget video, Grant feels the concept of Newton-John as a vixen-in-disguise might have worked better on paper. “I don’t think we quite got that to work if I’m really honest,” he says. Moving production to London, Grant fared better with the ’40s-themed “Stranger’s Touch”. He explains, “It seemed to me that ‘Stranger’s Touch’ was a perfect film noir idea. Like many music video directors of the day, we were all trying to be movie directors!” [laughs]

The small London club that bookended scenes in “Stranger’s Touch” also appeared in clips for “Make a Move on Me” and “Love Make Me Strong”, depicting the singer onstage with a band. Grant explains. “There was a limited amount of money. We couldn’t make a concept for every single video, so we had to decide, between Roger and ourselves, where we would spend the money.” For the video album, Grant also revisited Newton-John’s earlier hits, using the club as a backdrop for new clips of “Magic”, “A Little More Love”, and “Hopelessly Devoted to You”.

However, the double entendres of “Physical” were practically made for Grant’s camera. He recalls, “The genesis of that idea had actually come from Olivia, inasmuch as she was quite reticent to put that record out. It’s a great piece of pop music, but when she actually heard the finished mix, she panicked because of what the song’s about. She told Roger she thought they couldn’t put it out, but Roger said, ‘It’s too late. It’s already gone to the radio stations.’

“She said, ‘Let’s just set the video in a gymnasium because it’s about physical stuff.’ I went away and thought about it. I thought, That’s not funny enough. I spun it on its head and undercut the expectation: set it in a gymnasium, and you’ll expect to see her with very good-looking guys, so why not fill the place with fat ugly men? She’s going to knock them into shape. Halfway through, she’s getting nowhere with them and decides to leave the room and go into a shower. When she walks back into the room, of course, the guys have turned into hunks. That was the original ending. When I was thinking about it, I thought That’s just too obvious. There has to be another twist. I then said, ‘Why don’t we just make it that, suddenly, she realizes they’re all gay men?'”

Featuring choreography by Kenny Ortega, who’d worked with Newton-John on Xanadu, Grant’s video for “Physical” filled the screen with plenty of steam, sweat, and a charismatic performance from its star. “We had to have a meeting with the record company and go through all of the ideas because they were paying for it,” Grant continues. “I remember sitting in a room with about four or five executives, describing this idea and being faced with this silence. For about five minutes, nobody said anything. I thought at that point that they were going to fire me. Luckily for me, Olivia actually understood the humor and backed me.”