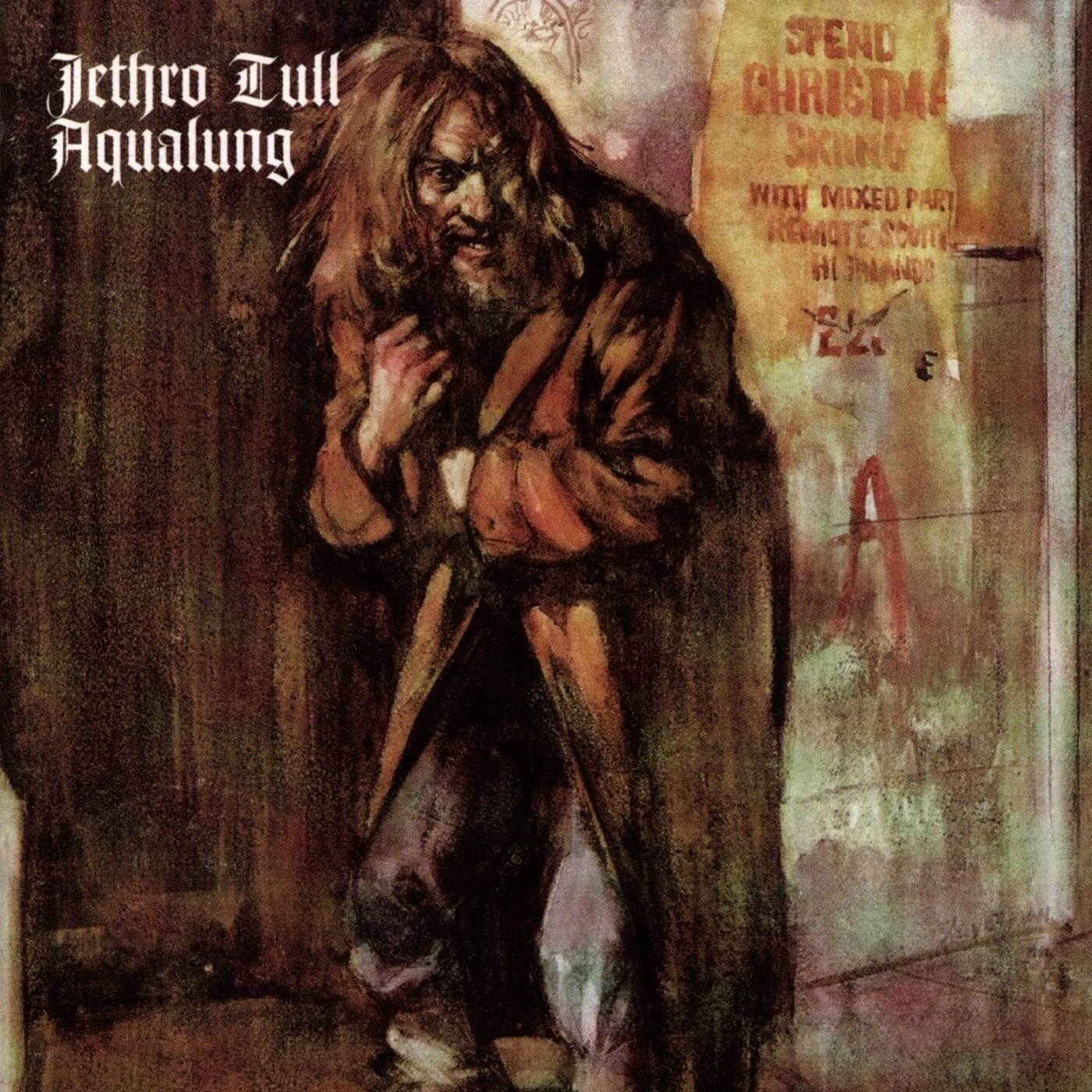

10. Jethro Tull – Aqualung [1971]

One thing that plagues even some of the better progressive rock music is how utterly of its time it can sound. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that!) Like most of the bands already discussed, few people would have difficulty tying the majority of these albums to their era. Jethro Tull, particularly on Aqualung, nevertheless manages to present a song cycle — meshing Ian Anderson’s acoustic strumming with Martin Barre’s abrasive electric guitar chords — that manages to sound not only fresh but vital, even today.

Understanding that the tunes are essentially asking “What Would Jesus Do?” in the context of a mechanized and materialistic society (circa 1971; circa 2015), Aqualung is prog-rocks J’accuse. Anderson makes a case for the better angels of the ’60s ethos, with nary a flower, freak-out or paean to free love. The ugliness of the way we tend to treat one another is, at times, reflected in the brutality of the music, and drives the relentless soundtrack to a state of affairs that arguably worsened as the “Me-Decade” got its malaise on.

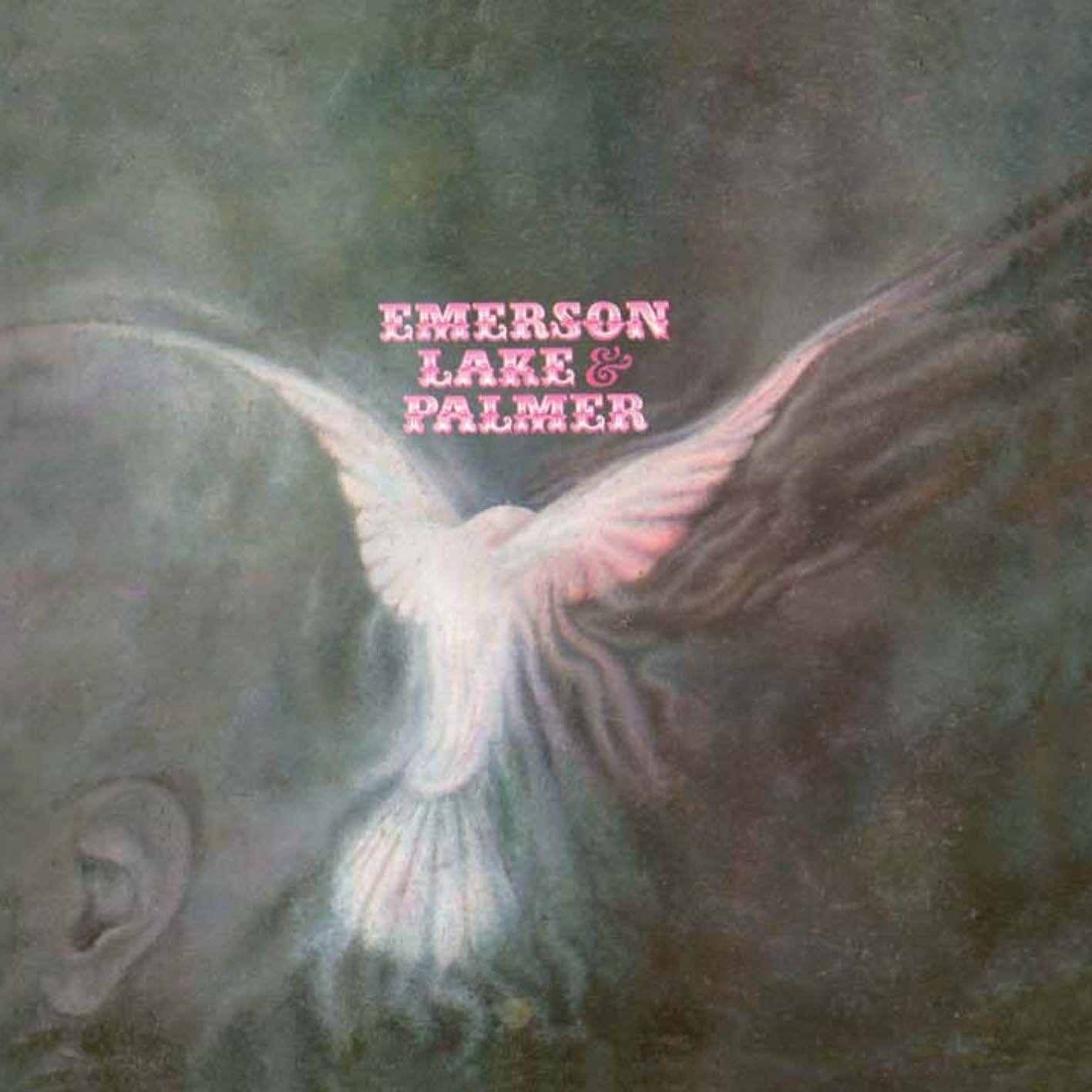

9. Emerson, Lake & Palmer – Emerson, Lake & Palmer [1970]

Their self-titled debut was not an introduction so much as a kind of coronation: We are geniuses, hear us roar! The ideas and styles crammed into these six songs are at once staggering and overpowering, yet they manage to pull it off so that it never seems superfluous or overwrought (that problem would surface later on in their career). If King Crimson, during their prime, were not satisfied until they upped the ante past the point of endurance (for the uninitiated or enlightened, that is), Emerson Lake & Palmer made indulgence and excess their calling card. Adventurous, audacious, and, yes, at times pretentious, ELP threw down a gauntlet and, at their best, produced works that still sound miles ahead, in terms of musical proficiency, conception, and execution, of what just about any other rock band is capable of achieving.

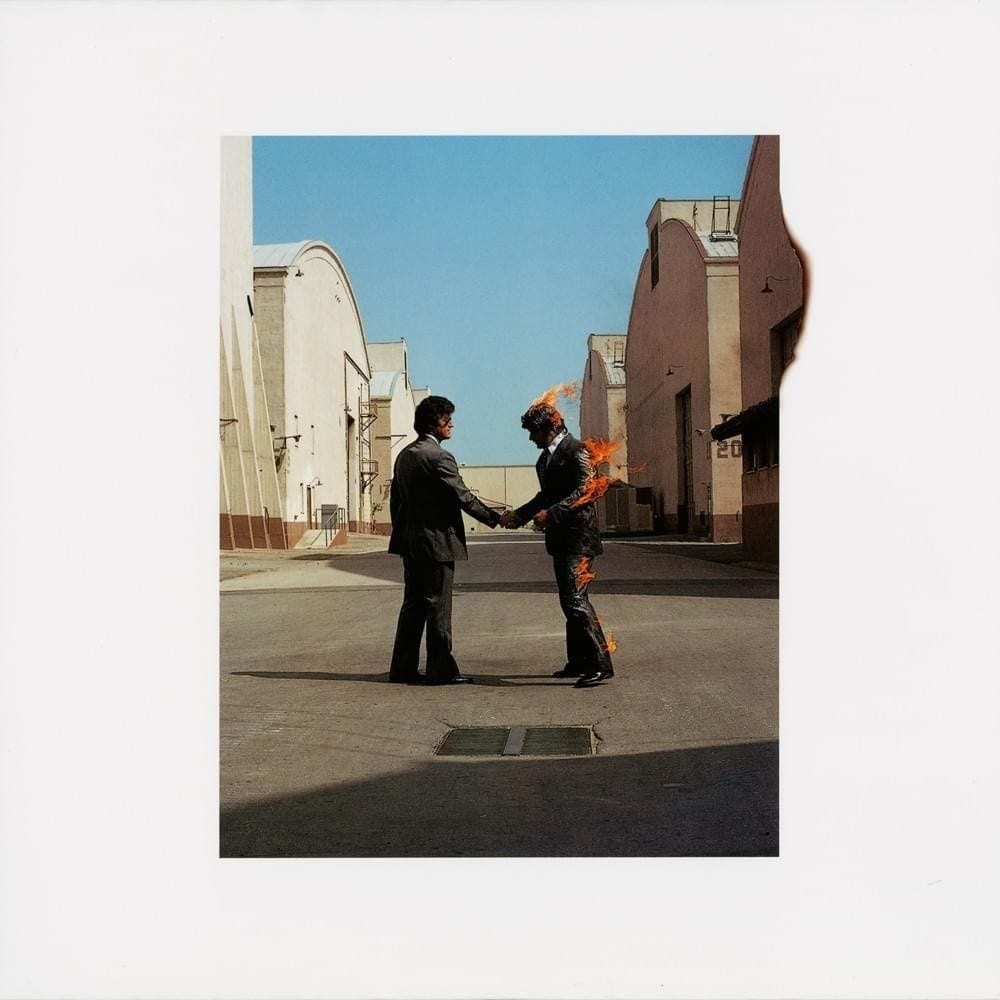

8. Pink Floyd – Wish You Were Here [1975]

An extended meditation on loss, the lyrics certainly address Syd Barrett and serve as equal parts explanation (of) and apology (for) what really went down in 1968. But Waters’ words are expressive enough to welcome additional, deeper interpretations. Certainly songs like “Have a Cigar” and “Wish You Were Here” speak to Loss with a capital L: loss of innocence, loss of intimacy, or loss of connection(s) to others as well as oneself. If the two-part suite “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” is a rousing elegy for Barrett, “Welcome to the Machine” manages to condemn stardom, the system (military, corporate, entertainment), and the eventual disenchantment that follows success, all while creating a seven-minute soundtrack to make Dystopia sound at once inevitable and irresistible.

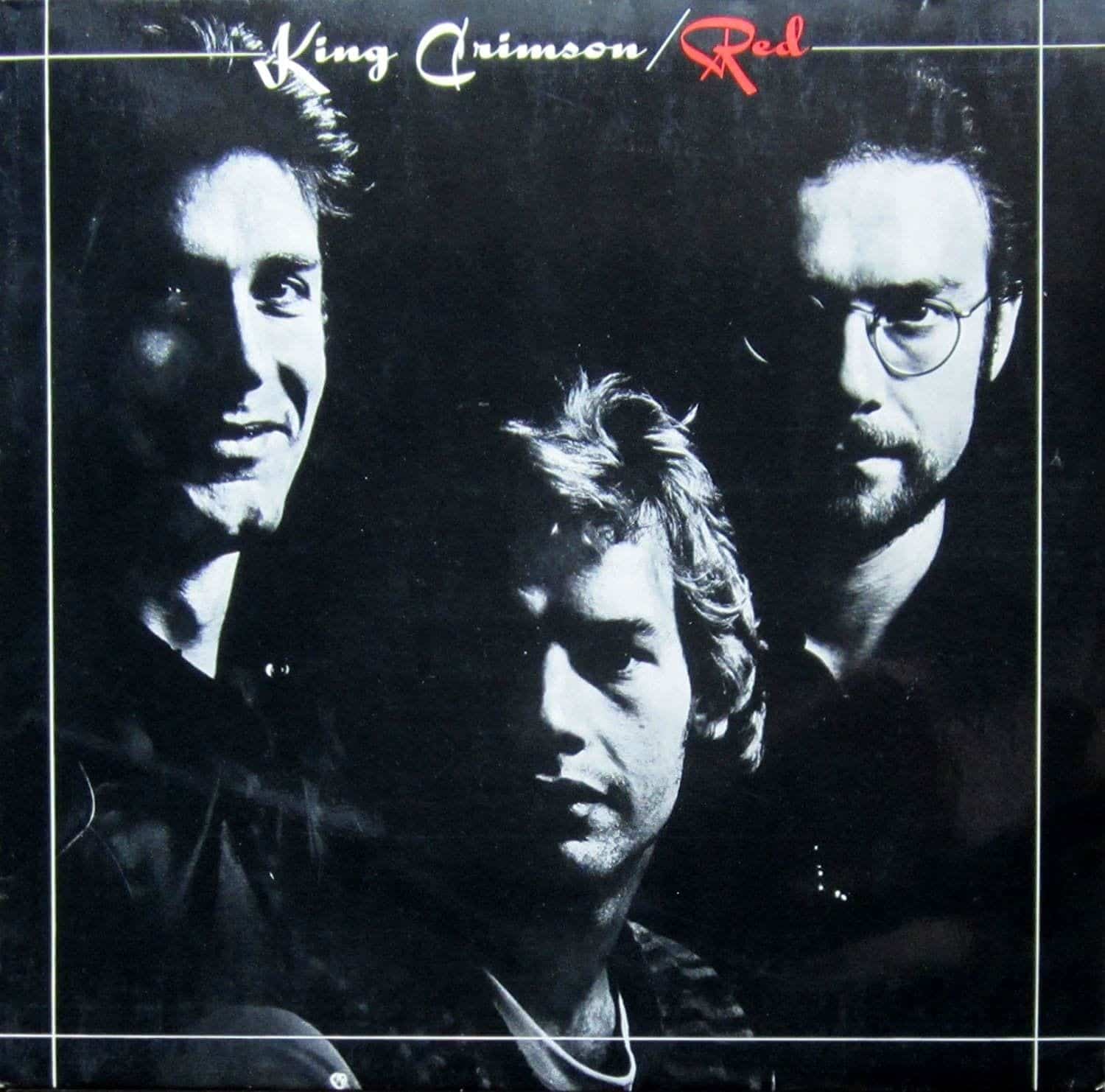

7. King Crimson – Red [1974]

Although King Crimson seemed, sonically, locked in to make a sustained run, Red turned out to be their final album of the 1970s. This was entirely Fripp’s decision, the result of burnout and likely, if understandably, residual exhaustion from his almost ceaseless work. Red begins and ends with signature songs — for the band and prog-rock. The title track is a yin yang of intellect and adrenaline, underscored by a very scientific, discernibly English sensibility: it’s the closest thing rock guitar ever got to its own version of John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps”.

The closer, “Starless”, is epic in every sense of the word; one of the all-time progressive rock masterworks. Brooding and heavy, fraught with feeling and foreboding, it’s an exercise in precision, the apotheosis of their “dread and release” formula. It builds an almost unbearable tension, breaking at last through the darkness; less like the tide retreating and more like an ocean disintegrating into the air. If ever a rock album could be said to invoke Poe’s famous “unity of effect” theory, Red remains one of the most fully felt, affecting artistic statements in the genre.

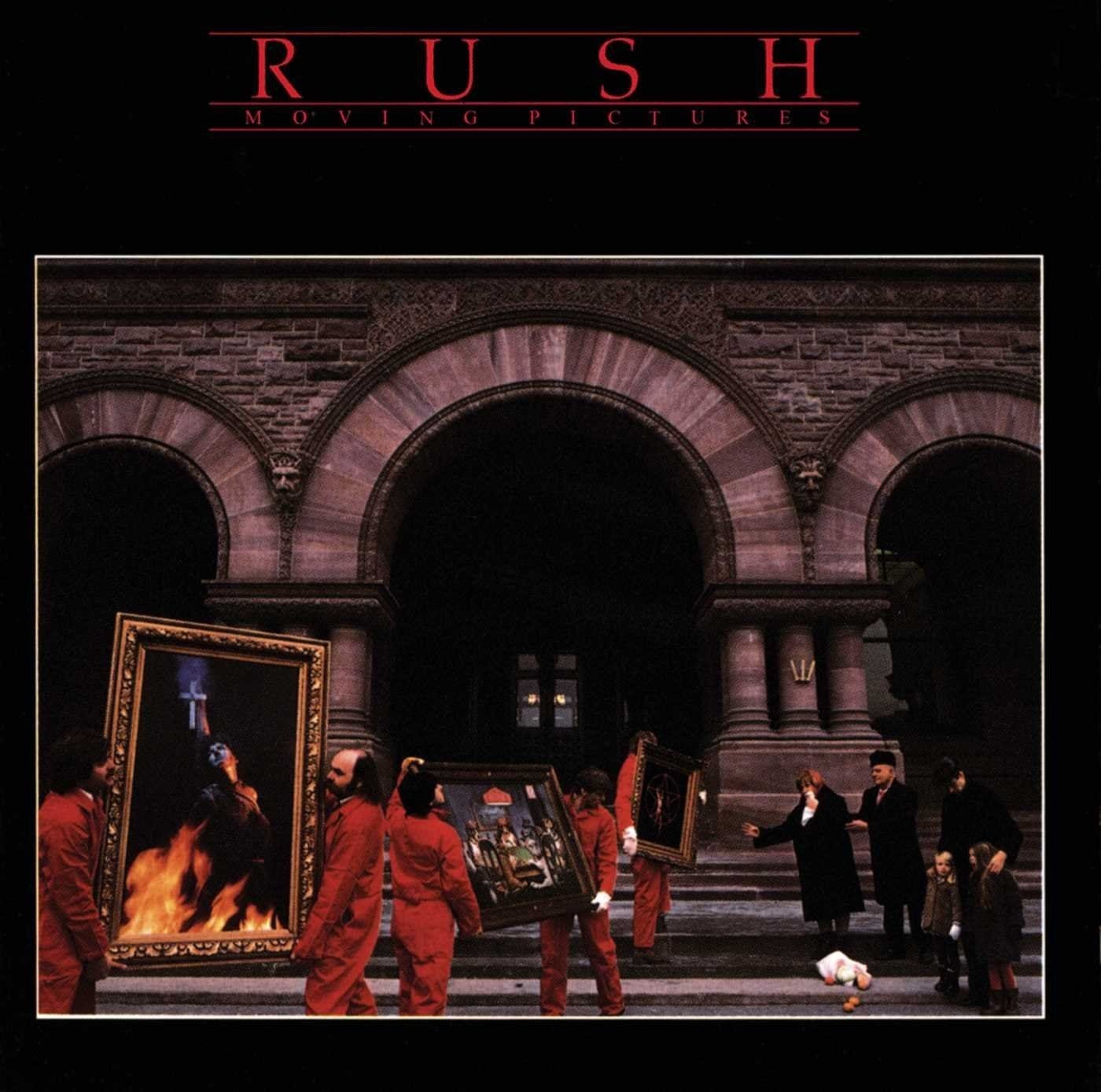

6. Rush – Moving Pictures [1981]

Rush arrived at the prog party later than their compatriots, but unlike other acts who began to both born out and fade away, this trio emulated the best aspects and steadily engineered their own wholly unique and rewarding style. Moving Pictures is, without any question, not only Rush’s masterpiece but one of those rare albums that epitomizes an era. It represents both a culmination and a progression: the peak of the band’s development as well as the blueprint for Rush’s subsequent work. More, it is a template of sorts for the way rock albums were made in the early 1980s.

Along with King Crimson’s Discipline, Moving Pictures illustrates that the first great era of progressive rock had been taken as far as it could, or should, go. Progressive rock became, in some ways, something very different than it was in the late 1960s, and that’s the point of its appeal. Always recognizable but seldom derivative, it pushed boundaries, sought new ways to explore sound and feeling, and strived to become, as Rush put it best, “emotional feedback on a timeless wavelength”.

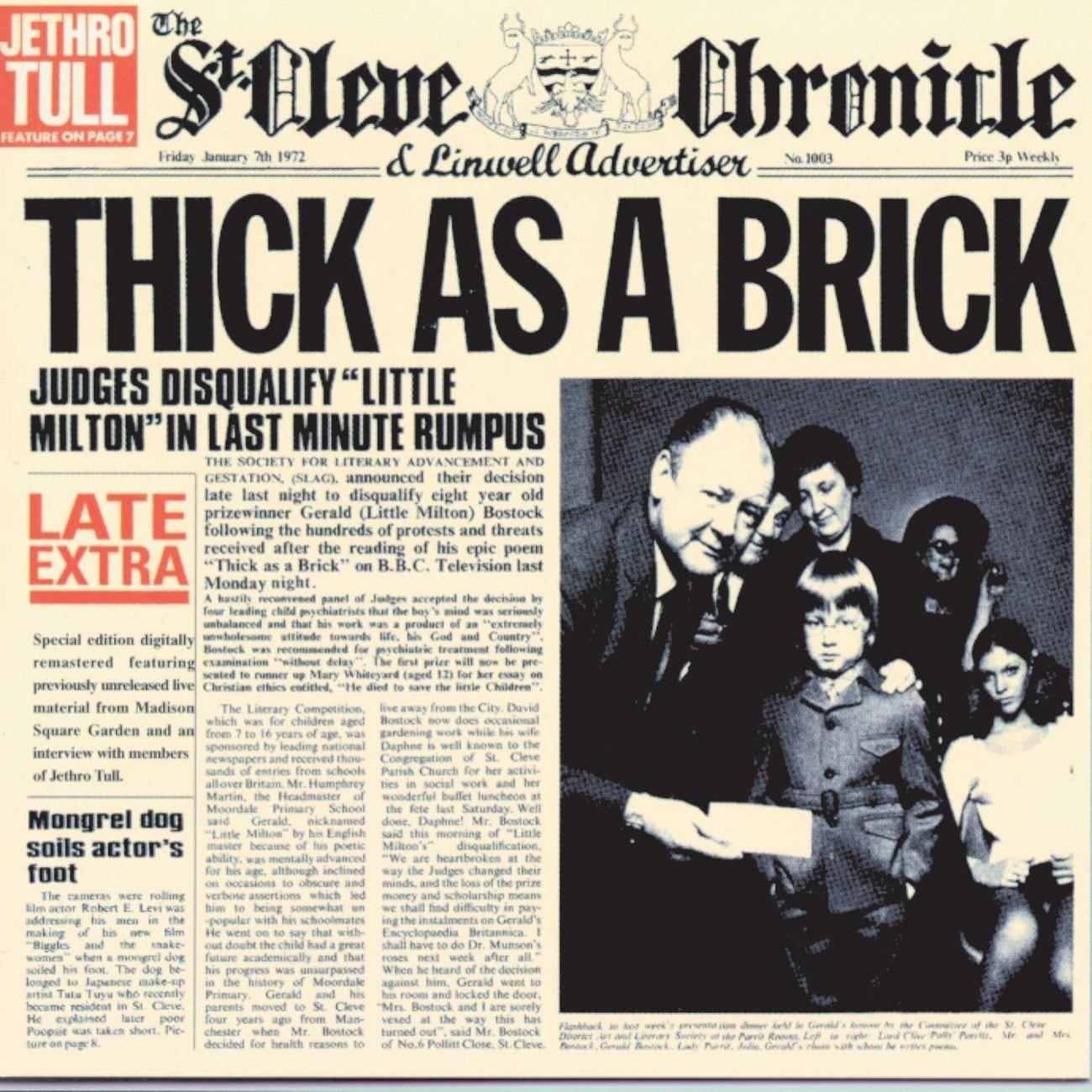

5. Jethro Tull – Thick As a Brick [1972]

Jethro Tull were on top of the world (and the charts) in 1972 when Thick As a Brick became the first pop record comprised of one continuous song to reach a widespread audience. The concept may have been audacious, but the music is beyond belief: this is among the handful of holy grails for progressive rock fanatics, no questions asked. If Aqualung doubled down on the “concept album” concept, Thick As a Brick functioned as a New Testament of sorts, signifying what was now possible in rock music.

Even with the side-long songs that became almost obligatory during this era, nobody else had the wherewithal to dedicate a full 45 minutes to the development and execution of one uninterrupted song (and Tull did it twice). Anderson had already proven he could write a hit and create controversial work that got radio play; now, he was putting his flute in the ground and throwing his codpiece in the ring.

Whatever else one may say about it, Thick As a Brick is the Ne Plus Ultra of progressive rock: between the extensive packaging (a faux newspaper that is equal parts Monty Python and The Onion). This was as ambitious as progressive music had been and arguably remains the ultimate (anti?) concept album.

4. Pink Floyd – Dark Side of the Moon [1973]

Perfect opening song. Perfect closing song. No, even that’s not quite sufficient praise. No other album begins and ends as sublimely as this one does. From the opening heartbeats to the sardonic assertion “There is no dark side of the moon, really… as a matter of fact it’s all dark”, this is rock music’s visionary apex. Dark Side of the Moon represents the ultimate balance of aesthetic and accessibility—demanding yet consistently satisfying—that the Beatles initiated with Sgt. Pepper.

For 741 weeks it was on the charts, and it somehow remains invigorating. It’s still capable of surprising you, whether it’s the reverb of Gilmour’s slide just before the (improvised) caterwauling on “The Great Gig in the Sky” or the ceaselessly rousing climax of Waters’ understated poetry in “Eclipse” (“And everything under the sun is in tune / But the sun is eclipsed by the moon”). This is it; it’s all in here, and it seldom got better than this.

3. Yes – Close to the Edge [1972]

Other bands came very close, but it seems safe to suggest no one else in the prog arena were as productive and proficient as Yes managed to be from early 1971 to late 1972: three masterpieces culminating in their tour de force, which approaches a level of ecstasy few outfits have ever approximated. While rightly castigated for bringing inane lyrics to an almost holy level, listening to Yes is like listening to opera: the words are, or may as well be, in a different language. It’s all about the sounds: that voice, those instruments, that composition.

The title track is one of progressive rock’s ultimate statements of purpose, worthy of every clichéd superlative imaginable: it really is epic, and it really does deliver delights only the rarest art offers. While he presents abundant evidence before and after these proceedings, his work on this album alone ensures Steve Howe immortal status. Throughout the proceedings there are no pauses, wasted moments or miscues: everyone assembled works in service of the songs, resulting in a unified, utterly convincing proclamation, a truly joyful noise.

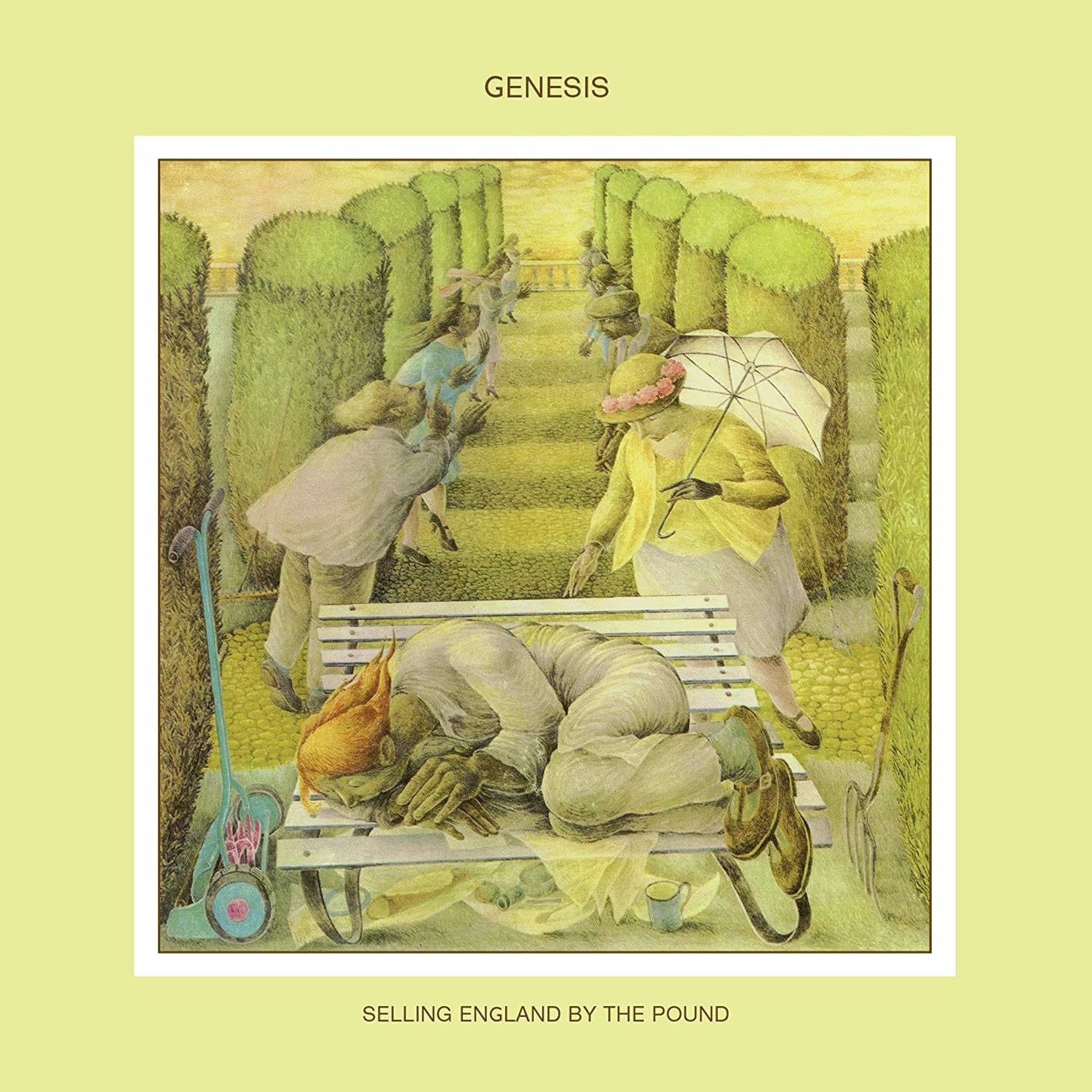

2. Genesis – Selling England by the Pound [1973]

Selling England by the Pound is the most satisfying and fully realized Genesis recording, a period piece that recalls the past while being utterly of its time: the elegiac keyboards at the end of “Epping Forest”, for example, invoke a police siren outside a football stadium filtered through a black and white telly in an English pub, circa 1973. It’s elaborate but controlled, far-ranging but focused, and it achieves a unity — in words, sound and especially feeling — that necessarily ranks it as a high watermark of progressive rock.

Each member does career-best work, and the primary players all get a suitable showcase: Hackett serves up a shredfest on “Dancing with the Moonlit Knight”, and history has correctly noted that his tapping technique provided a template for the young Eddie Van Halen. Banks turns in a piano tour-de-force on “Firth of Fifth” that must have given even Keith Emerson pause (the solo Hackett uncorks mid-song might well earn him all-time progressive rock MVP status); and Gabriel puts his words, voices, and every ounce of his showmanship into “The Battle of Epping Forest” and “The Cinema Show”.

The mastery throughout is all-time, for the ages; a bottomless pit of riches you can plunge into and float around blissfully, for the rest of your life. The poetry, puns, reportage, riffs on modern life (Oh, the humanity…) and, as always, a yearning not-quite-nostalgia for a quieter and less complicated time.

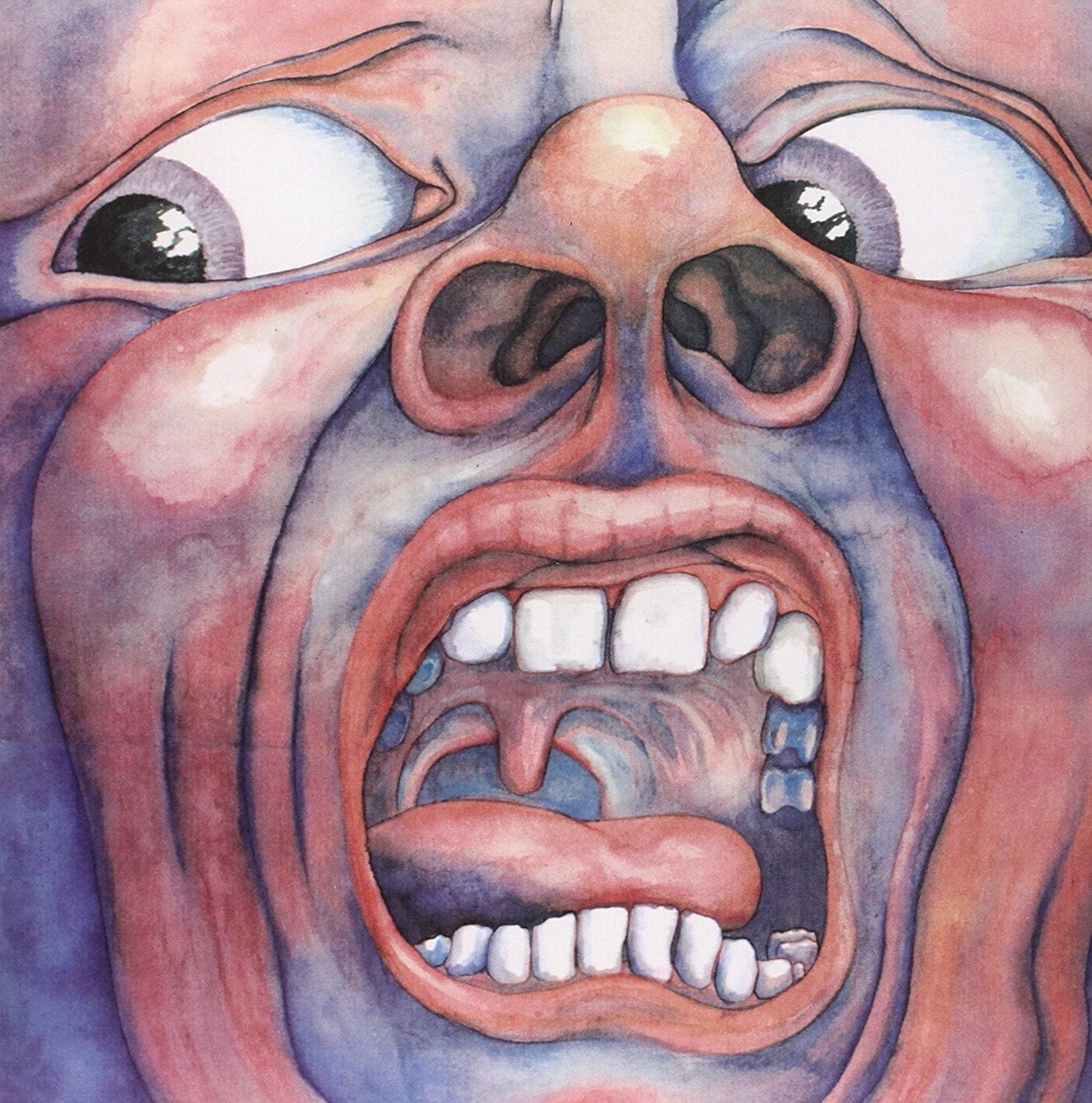

1. King Crimson – In the Court of the Crimson King [1969]

The Rosetta Stone, and still the purest and most perfect expression of the progressive rock aesthetic. To fully fathom what In the Court of the Crimson King signifies, it’s useful to consider it as less an uncompromised statement of purpose, and perhaps the first influential album that forsook even the pretense of commercial appeal. To understand, much less appreciate, what these mostly unknown Brits were doing you have to accept their sensibility completely on their terms. Importantly, this was not a pose, and it was not reactionary; it still manages to seem somehow ahead of its time as well as — it must be said — out of time. Of course, it came out of an era and the minds from which it was conceived, a dark, sensitive, and undeniably psychedelic space.

So, what is it, exactly, that King Crimson accomplished on the album that arguably remains their most fully realized vision? It has all the necessary ingredients: impeccable musicianship from all players (but special props must be doled out to Ian McDonald, whose flute and saxophone contributions grant the material its majestic, at times ethereal air), rhythmic complexity, socially conscious lyrics — courtesy of Peter Sinfield, and an outsider’s perspective that is neither disaffected nor nihilistic. It speaks from the underground but is grounded in history and looks forward, not backward.

Editor’s Note: This article was original published on 17 November 2015. It has been updated and reformatted for modern browsers.

- The 100 Best Classic Progressive Rock Songs: Part 5, 20-1 ...

- The Best Progressive Rock of 2014 - PopMatters

- The Best Progressive Rock of 2011 - PopMatters

- The 2018 Progressive Rock/Metal Preview - PopMatters

- The Best Progressive Rock (and Metal) of 2013 - PopMatters

- The Best Progressive Rock and Metal of 2016 - PopMatters

- The Best Progressive Rock and Metal of 2017 - PopMatters

- The 10 Best Progressive Rock Albums of the 2000s - PopMatters

- The Best Progressive Rock/Metal of 2018 - PopMatters

- The 10 Best Progressive Rock/Metal Albums of 2020 - PopMatters

- The 10 Best Progressive Rock/Metal Albums of 2020 - PopMatters