Hüsker Dü – Zen Arcade

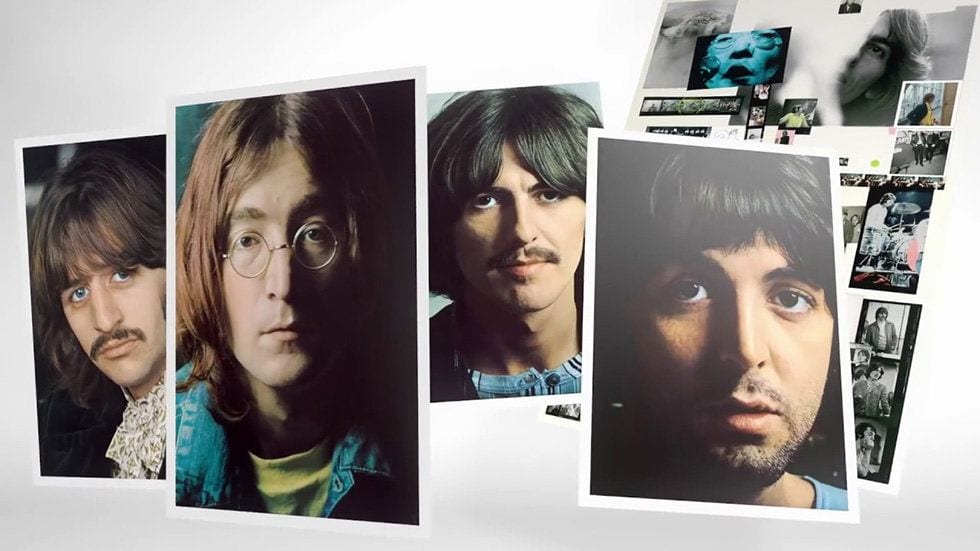

Cowboy-narrated songs and all, it was the independent US label SST Records that anticipated alt-rock’s engagement with the archetype at hand when, in July 1984, it promoted the sophomore studio LP by Minneapolis hardcore band Hüsker Dü as: “The most important and relevant double album to be released since the Beatles’ White Album.” The claim, in reference to Zen Arcade, was made three years into the Reagan presidency when a long-in-the-tooth Van Halen and their hair-metal affiliates Whitesnake and Bon Jovi ruled the rock mainstream, being pretty bizarre in conjunction with an underground act who had so far only released an LP (Everything Falls Apart) and an EP (Metal Circus) on their own label, Reflex Records.

Yet it meant that the trio of Grant Hart, Bob Mould, and Greg Norton were able to capitalize on the idea of the Beatles breaking free of their musical constraints on the White Album and finding a broader audience, in a coming-of-age moment for the rock scene they represented. They, therefore, conjured up the Beatles’ rejection of psychedelic rock on their 1968 record in their offering of a four-sided release that represented, as Michael Azerrad has put it, a “strenuous refutation of hardcore orthodoxy” (Our Band Could Be Your Life, 2003). They could be seen, in this way, to transcend the style typified by contemporaries such as the Replacements, Black Flag, and Minutemen of playing at breakneck speed and rasping over aggressive drums and distorted guitars, by instead fulfilling the wishes of their singer-guitarist Bob Mould to “go beyond the whole idea of ‘punk rock’ or whatever” (Matter, September 1983).

Hüsker Dü achieved their White Album-aligned musical liberation by delivering a multi-stylistic concept album of 23 songs, focusing on a boy who leaves his broken home to make his way in a cruel and unforgiving world. They purposed the music to reflect the changing nature of the narrative, in which the boy flirts with joining a cult, meets a girl who fatally overdoses, and retreats into himself on his return home.

They principally interweaved hardcore with melody and introspection, by which they developed an affinity with the Athens band R.E.M., who had themselves shown a rapid musical progression from the urgent post-punk they demonstrated on the independent Hib-Tone label to the jangly folk-rock of their second album Reckoning (1984) for IRS. In this, they shared an evident fascination for 1960s groups like the Byrds and the Troggs, through which they acquired a quirkiness that made them staples of US college radio.

Hart and Mould, à la Lennon and McCartney on the White Album, added to the diversity of Zen Arcade as two competing songwriters within the band, with Hart largely categorized as “the angry one”, and Mould “the poppy one”. As such, they offered up a strident rock opener (“Something I Learned Today”), a folky acoustic number (“Never Talking to You Again”), a brief piano instrumental (“Monday Will Never Be The Same”), psychedelic rock (“Hare Krsna”), and a trippy 13-minute instrumental freakout (“Reoccurring Dreams”), while the sleeve notes declared that “everything on the record is first take”.

The ambition in the music, in turn, earned them mainstream press attention in the form of David Fricke’s Rolling Stone review in February 1985, calling the album a “blueprint for a brave new music”. Moreover, as if to justify the White Album comparison that had been applied to them, the band included the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter” in their live set, a song which had served to encapsulate the Beatles’ revived power as a live ensemble on their 1968 double. Hüsker Dü no doubt adopted the song to highlight their own newly acquired skills in integrating punk with melody, going on to issue it on their “Don’t Want to Know If You Are Lonely” EP in March 1986.

- The White Album: Side Three - PopMatters

- The Beatles: White Album - Side 2 - PopMatters

- Birthday: The White Album Turns 40 - PopMatters

- The White Album: Side One - PopMatters

- The Beatle's White Album

- The White Album: Side Three - PopMatters

- The White Album: Side Four - PopMatters

- Birthday: The Beatles' White Album 40th Anniversary

- Counterbalance No. 14: The Beatles' 'The Beatles' AKA "The White ...

- The Glorious, Quixotic Mess That Is the Beatles' 'White Album ...

- Riotous and Hushed: The Beatles' 'The White Album' - PopMatters

- Kristin Hersh Discusses Her Gutsy New Throwing Muses Album - PopMatters