Physical — The Album

Olivia Newton-John greeted the 1980s as one of pop’s reigning queens. Her marquee value equaled platinum-selling hitmakers like Donna Summer, Diana Ross, and Barbra Streisand, who each ushered in the new decade with albums that recalibrated their sound. Newton-John’s work on the Xanadu soundtrack, Summer’s new wave excursions on The Wanderer (1980), the CHIC Organization’s production of diana (1980), and Streisand’s collaboration with Barry Gibb on Guilty (1980) led 1980 with stylish and impeccably produced releases.

Only two months after Newton-John held the top with “Magic”, Streisand reached number one with “Woman in Love” produced by Gibb and Bee Gees co-producers Albhy Galuten and Karl Richardson. Earlier that year, the team had also helmed Andy Gibb’s duets with Newton-John for his third solo album, After Dark (1980). “I remember when we did the duets with Olivia,” says Galuten. “She was fantastic. She was on. I was stricken! I think we may have done some of the vocals with Barry singing with Olivia because there was a lot of struggle getting a vocal out of Andy.”

As Newton-John and Andy Gibb’s recording of “I Can’t Help It” climbed to number twelve in the spring of 1980, Barry Gibb completed his work on Guilty. The album featured three of his writing collaborations with Galuten, including “What Kind of Fool”, “Never Give Up”, and “Make It Like a Memory”. The team also offered Streisand a breezy ballad called “Carried Away”. “When we wrote those songs, it was not Streisand’s style,” notes Galuten. “It was Barry being stimulated by what he thought would be interesting and fun to do with her.”

Though Streisand passed on “Carried Away” , Newton-John recorded the song for her first full-length set of the 1980s — Physical. “She got a hold of it somehow,” Farrar chuckles. “I think maybe Barry gave it to her. He’s always been a hero of mine from way back when the Bee Gees first started, and I was in Australia. I met him a few times over the years, and he’s just the sweetest guy.” Newton-John had also known the Bee Gees from years earlier, having previously scored a Top Five country hit in 1976 with her version of the trio’s “Come on Over”.

Retaining the integrity of Gibb’s original demo, “Carried Away” glistened with Newton-John’s radiant interpretation. “It was an homage,” says Galuten. “I think John’s a brilliant producer. I have a tremendous amount of respect for him. The thing with ‘Carried Away’ is that it seems so straight ahead. It’s not your average time signature, but it doesn’t seem so unusual because the melody leads you there. It’s not like you have to count. It seems totally natural.” Indeed, Newton-John rendered the song with a beguiling ease that belied the song’s rather unconventional structure.

“Carried Away” was one of several songs on Physical that hailed from outside projects. In between scoring songs for Xanadu, Farrar had also begun writing and recording his solo debut for Columbia, John Farrar (1980). Cashbox drew favorable comparisons to the Bee Gees and Kenny Loggins upon the release of the album’s lead single “Reckless” in November 1980, championing the tune’s “lilting electric piano melody” and “distinctive instrumental touch”. Other self-penned songs like “Cheatin’ His Heart Out Again” and “From the Heart” replicated the tuneful creativity he brought to his productions for Newton-John, who’d sing “Reckless” with Farrar decades later on Olivia Newton-John & Friends: A Celebration in Song (2008).

However, the quiet hush of “Falling” emerged as a sleeper cut on Farrar’s debut. “I remember with that song I didn’t want to have an actual chorus,” he says. “I wanted the ‘falling’ lines to be at the end of the verse rather than having a verse and then a chorus. It’s three verses and a middle. I was worried that the bridge chords were a bit out there, but it seemed to work okay. I remember I couldn’t come up with an intro and I finally came up with an intro one night. At the end of the intro, when it went into the verse, I wanted it to feel like it was kind of in a different key, or not where you expected it to be. It took me awhile to come up with that.”

Newton-John’s own rendition of “Falling” floated in weightless splendor. “There’s a warmth and an intimacy that she manages to put across that seems to touch people,” says Farrar. “Olivia understood singing quietly,” adds Holman. “As an engineer, I understood being able to take something that’s small and turn it into something that’s huge, sonically. I made sure that her headphones were perfectly balanced and that her voice was right in the middle of her head. I used a compressor as a volume control and also, obviously, as a compressor. I’d have it in my lap and ride her vocals continuously from the beginning of the song to the end of the song.”

“Recovery”, another choice tune from Farrar’s solo album, furnished Physical with a particularly inspired showcase for the singer. “Olivia liked that song, and I was very happy that she wanted to do it,” says Farrar. “I probably talked her into it!” Farrar wrote “Recovery” with Tom Snow, who chuckles when recalling the catalyst behind the song. “I think John and I were both just sitting around talking and bitching and being bitter!” Nevertheless, “Recovery” radiated a magnetizing allure, even as Newton-John declared “Don’t worry ’bout my recovery / ‘Cause lover you won’t recover me.”

Farrar’s opening guitar on “Recovery” immediately commanded attention. “John’s playing is exquisite,” says Holman, who extracted a bright, ringing quality from the guitar through a special kind of compression. “In those days, we used to spend a lot of time on those tracks,” says Farrar. “We didn’t have anything like Auto-Tune. You had to really struggle to come up with different sounds. David was great because if I ever said to him, ‘Can we try this?’ he would never say no. He did a really good job with the mixing and the recording and everything. Lots of credit goes to him on that.”

Marimba flourishes complemented the island setting of the lyrics, a key detail that distinguishes Newton-John’s version of “Recovery” from Farrar’s original recording. “It’s a remarkable piece,” says Snow. “John wouldn’t take a song to Olivia that he didn’t think was 100%. As a co-writer with John, you never felt like you were fighting against some kind of insecure ego. He was absolutely one of my favorite collaborators in that sense.”

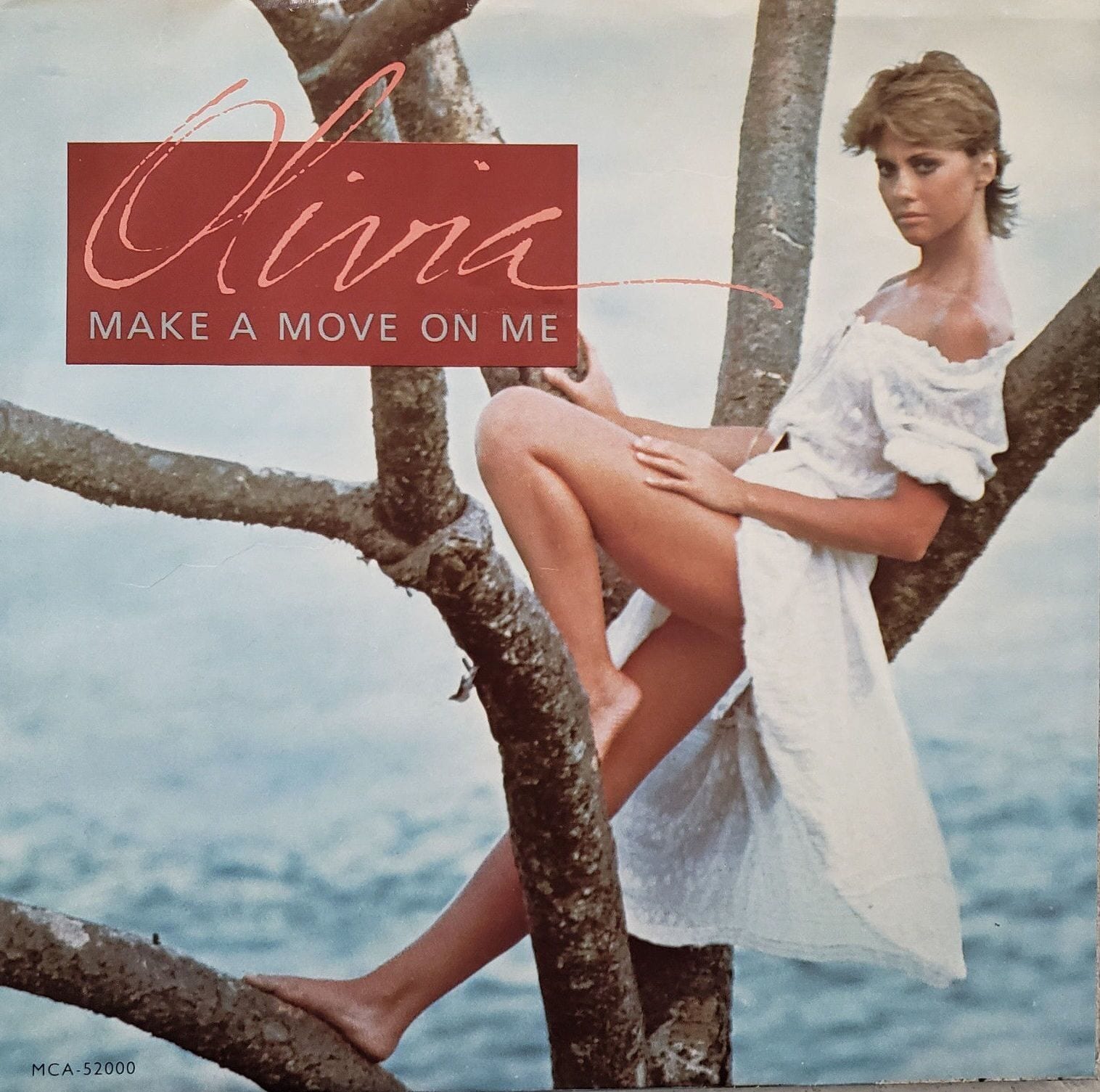

Farrar and Snow led each other to new heights with “Make a Move On Me”, arguably the duo’s crowning achievement as collaborators. “Tom and I both loved chord structures,” says Farrar. “Sometimes he would play the chord sequence and I would play a melody on the top or vice versa. With ‘Make a Move on Me’, I remember I couldn’t come up with anything in the verse. Tom came up with that synth part that was great.” The high-pitched melody that Snow conceived for the intro primed listeners for three minutes of pop bliss.

“‘Make a Move on Me’ has three distinct tonal centers,” says Snow. “It starts off in F and then goes to A-minor and then John figured a way to get it to E-flat in the chorus. He came up with that brilliant [sings] ‘Won’t you spare me all the charms and take me in your arms / I can’t wait’. It was amazing. There are very few pop songs that have that kind of harmonic structure to it. I thought we did a hell of a good job on that one.

“John had Carlos Vega come in to do the drum loop and I believe he came back a second time to fill out the track. I came up with the bass line. John loved it and had me play it. He said, ‘Let’s make a loop!’ I’d be sitting there in David’s studio, sweating, trying to get it absolutely perfect, doing manually what Pro Tools does with a button now. We didn’t have sequencers at that point. John would say, ‘Do it again Tom. It’s almost there.’ That went on for a couple of hours until it was absolutely spot-on, in the pocket. I think we made a four-bar loop. David cut the loop and then edited it into other parts of the tune.”

Sonically, “Make a Move on Me” is a shining paragon of synthesized sounds. The Prophet-5 synthesizer, in particular, polished the song with a warm, high-tech gloss. “When the Prophet-5 came out, it had this milky, sweet sound,” Holman notes. “It was one of the best-sounding things. The Oberheim was kind of cool but the Prophet fit so well into the recordings and it was just a fabulous instrument. It looked really sexy.”

Newton-John only amplified the sexiness of “Make a Move on Me” as her voice conveyed everything from simmering desire to unmitigated euphoria. However, the sex quotient on Physical climaxed in the title track.

“People say ‘Physical’ was written for Rod Stewart,” says Steve Kipner, dismantling a decades-old myth. “It actually wasn’t written for him, but I imagined someone like Rod Stewart might record it.” Kipner never dreamed that Olivia Newton-John would be the one to immortalize a little tune he and Terry Shaddick wrote together one afternoon.

Long before “Physical” became a phenomenon, Kipner had been acquainted with Newton-John, plus Farrar and his (future) wife Pat Carroll, when they performed in different groups around Melbourne and Victoria during the 1960s. “In those days, there were a few Australians out there going for it,” he continues. “Olivia was one of the people that seemed to get a foothold first. John was in a band called the Strangers. I was in a band called Steve & the Board. He was a little bit older than me, so I thought of them as a real band whereas my band, today, would be considered a punk band. I remember thinking, That guy is the real deal.”

Following a stint in England, where Kipner’s duo Tin Tin recorded a Top 20 hit “Toast and Marmalade for Tea” (1971) produced by Maurice Gibb, Kipner moved to Los Angeles, reuniting with several of the musicians he’d known in Australia. He continues, “A lot of Australian singers were here in LA and everybody kind of knew all the others. I didn’t have much money. I was pretty much starving. When John and Pat would have a party, I’d think, Oh, that’s great that I’m invited. That means that I can get to eat! I would always be first in line for the buffet.” [laughs]

Kipner’s own fortunes changed while recording his Elektra debut Knock the Walls Down (1979). Produced by LA studio wünderkind Jay Graydon, the set featured a first-rate roster of players like David Foster, Jeff Porcaro, David Hungate, Michael Omartian, and Greg Mathieson. During the session, Graydon invited Kipner to write a few songs for another project he was producing, Alan Sorrenti’s L.A. & N.Y. (1979). Though Knock the Walls Down stalled on the charts, one of Kipner’s tunes “All Day in Love” doubled as the B-side to Sorrenti’s “Tu Sei L’Unica Donna Per Me”, which sold over a million copies in Italy.

Attaining more success with one song than his own solo album, Kipner realized that writing for other artists promised greater commercial potential. “When you write songs, you write songs about being in relationships and being in love and all that,” he says. “Terry and I thought, Let’s just write a song about the physical side of love. I didn’t think it would be called ‘Physical’. We were going to write a song about sex, basically. I did the demo on a little four-track Teac. I had a little drum machine that I borrowed that had two pre-sets, ‘Rock 1’ and ‘Rock 2’, ‘Bossa Nova 1’ and ‘Bossa Nova 2’. I used ‘Rock 1′. I think it’s exactly the same one that Hall & Oates used on “I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do)’.”

After cutting the vocal, Kipner played “Physical” for his friend and manager Roger Davies. “Roger worked for Lee Kramer, who was Olivia’s manager and boyfriend at the time,” he says. “I went to play the demo for Roger because he was my best mate, not thinking it was for Olivia. Lee Kramer also managed Mr. Universe. I think Lee heard the song through the walls. He didn’t necessarily think that ‘Physical’ was a hit song, but he thought that if Olivia recorded it then he could also put Mr. Universe on the album cover with Olivia! She came into the office that afternoon and I guess that’s when they played the demo for her.” Ultimately, Mr. Universe was scarcely needed at all.

Even in demo form, “Physical” was an undeniable hit. “Stevie’s always been tuned into what’s happening,” says Farrar. “Before I had anything to do with it, it sounded like a hit record. I stuck close to that. There’s a distorted guitar that’s pulsing in there. I had this old Roland drum machine, and we used that to gate an electric guitar and get that pulse.”

Farrar enlisted a stellar cast of musicians including Toto bassist David Hungate, Carlos Vega (drums), Lenny Castro (percussion), Bill Cuomo (Prophet), and Gary Herbig (horns) to embellish the song’s crisp, streamlined groove. Hungate’s bandmate Steve Lukather laid down a searing guitar solo. Holman recalls, “I think John was fooling around with a solo and he said, ‘Nah, I should really bring in Steve’ … and that’s Steve Lukather. I was talking to Steve weeks before about something, and he was all excited about this new guitar that had the Floyd Rose Bridge. I don’t remember what kind of guitar it was — might have been a Fender Strat — but the Bridge was what was unique.

“I always had amps set up in the room ready to record. I had a Princeton amp, which I still have, sitting there with a microphone on it right next to the couch where John was working. I remember it was a really hot day. Steve came flying in. He goes, ‘I finally got this guitar. Check this out man!’ He plugs it in. ‘I’m not even going to tune the guitar.’ I rolled the tape and hit record. He played the guitar solo and that was the guitar solo for ‘Physical’. That was it. I could see him stretching the notes but I remember thinking, Damn, it’s pretty amazing that the guitar’s still in tune. It’s a testament to the talent of the people involved that a guy could walk in off the street, plug in a guitar, and play that guitar solo without ever having heard the song. It just came from the spirit of his talent.”

In just five syllables — “let’s get physical” — Olivia Newton-John captured the tune’s contagious appeal. The steamier aspects of the verses, considerably tame by 21st century standards, took the singer from “totally hot” to a more “horizontal” kind of heat. “I couldn’t imagine Olivia would sing those lyrics, but I’m obviously glad she did,” Farrar chuckles. “It was a great song, a very catchy song, but Olivia’s image was always very girl-next-door. Even during the final playback, she looked at me and said, ‘Do you think I can get away with this?'” [laughs] Regardless of the content, Newton-John’s performance evidenced strength, exuberance, and a playful strand of sensuality … all the elements of a blockbuster waiting to explode.

While both the title track and “Make a Move on Me” would pilot the album to double platinum certification, “Stranger’s Touch” kept Physical spinning under the stylus from start to finish. “It didn’t sound like a single, but it sounded like a really good song,” says Kipner, who wrote the tune with Farrar. “We literally picked up a couple of guitars and started writing the song. Songwriting is like ping-pong. Someone says a line or an emotion, and then the other person hits it back to you with another suggestion. ‘Stranger’s Touch’ just came out.”

Farrar continues, “I remember a little bit about that. I think I went up to Steve’s house one morning. We started ‘Stranger’s Touch’ there and then finished it at my place. We’ve known each other for so long, we spent most of the time laughing!” Farrar’s sinuous bass line anchored the rhythm and gave the song a distinctive groove. “I wasn’t really a bass player,” he says. “I tried to play it as aggressively as I could and I remember my thumbs started to bleed. [laughs] I had blood all over the place!”

Newton-John contoured the melody with a smooth and sultry style. The chorus spotlighted her more strident approach, reflecting both the torrid scenario of the lyrics and Farrar’s rock-tinged production. Just by shouting “he’s overpowering me”, she brought the track to a feverish standstill.

“Stranger’s Touch” also featured prominent background vocals from Farrar, whose voice seemed to peer through shadows in certain parts of the song. “John’s got a voice that fits beautifully,” says Holman. “He would do most of the backgrounds after Olivia did her lead. He’d work on the parts and hone them. It wasn’t a part along with Olivia, it was a part that supported Olivia. That’s what I really appreciate from him and probably one of the greatest lessons that I learned from Farrar. ‘Does this support what’s going on?’ As a singer on a track, you have to relinquish your ego to what you think you should do, to supporting the song and the artist.”

The Australian contingent behind Physical — Farrar, Gibb, Kipner, Roger Davies, and Newton-John — mushroomed with songwriter/producer Terry Britten, who’d made a mark in Australia during the 1960s. Kipner recalls, “When I was a kid in my first band, and John Farrar was in the Strangers, Terry Britten was in a group called the Twilights. The singer was Glenn Shorrock (from Little River Band). I remember going to a show. They somehow got a copy of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band before it was released in Australia. They played the whole album as a band. It was amazing.”

Britten left Australia for England around the same time as Farrar and Kipner in the early ’70s, subsequently playing guitar on Newton-John’s Music Makes My Day (1973) and Clearly Love (1975) albums. “Olivia’s a great girl who I had the pleasure of touring with,” he says. A few years after Britten scored a major hit as a co-writer on Cliff Richard’s “Devil Woman”, he’d contribute one of Physical‘s more bracing cuts.

“I was involved in a movie called The Pirate Movie (1982) with Kristy McNichol and Christopher Atkins that filmed in Australia,” Britten continues. “I wrote the songs and amongst them was ‘Love Make Me Strong’. It was intended for Kristy to sing. John was in touch with the producer, I’m not sure how, maybe as an advisor. He thought ‘Love Make Me Strong’ would be great for Olivia and asked if he could have it. I was delighted of course, so I wrote another song on set called ‘Hold On’ to take its place.”

Britten had penned the song with Sue Shifrin, who also collaborated with him on “See How the Love Goes” for the Pointer Sisters before he forged a successful, Grammy-winning partnership with Graham Lyle on Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got to Do With It”. Newton-John tore into “Love Make Me Strong” with a fervor that nearly caught fire. “John pretty much stuck to the demo, obviously with a great vocal from Olivia,” says Britten. “Her vocal was a lot edgier than previous songs and so showed another side to her talents.” Newton-John would adopt a similar vocal stance on another Britten tune “Toughen Up” (co-written with Lyle), a single from her last MCA album, Soul Kiss (1985).

Of the songs on Physical, “Silvery Rain” had the deepest roots, dating back to Farrar’s early years in England. “When I went to England in 1970, I joined a group with Hank Marvin and Bruce Welch,” he says. “Sometimes we’d go out as Marvin, Welch & Farrar and sometimes we’d go out as the Shadows. ‘Silvery Rain’ was a song that Hank wrote on the first album (Marvin, Welch & Farrar, 1971).” Released shortly after U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson founded Earth Day, the song offered a sobering look at the toxic effects of pesticides.

A decade after the trio’s original recording, plus original Shadows frontman Cliff Richard’s own version on Columbia, Farrar recast “Silvery Rain” for Physical. “I wanted to go a little deeper into it,” he says. “I’ve always loved that song, so it wasn’t hard to talk Olivia into doing it. She’s very much an environmentalist, so that song was perfect for her view of life.”

Farrar masterfully modernized Marvin’s tune for the 1980s, juxtaposing the brightness of his guitar and the crystalline tone of Newton-John’s voice with a bass line that evoked a foreboding atmosphere. “That was the first Roland guitar synth that came out, and it was extremely unreliable,” Farrar recalls. “David managed to make it sound like a really big bass sound.” Holman also contributed an effect of his own in the second verse. “If you hear the wind, that’s me blowing into a microphone,” he says.

Elsewhere, Holman and Bill Cuomo simulated a crop duster that careened from the verse into the chorus. With guitars raging, Newton-John shouted “Fly away Peter, fly away Paul, before there’s nothing left to fly at all”, her urgent plea piercing the discord. No less a cultural arbiter than The New York Times praised Farrar’s work on the track, noting how “his arrangement achieves a gossamer translucence that one rarely hears on a pop album” (17 January 1982).

Newton-John herself also authored an ecologically minded song for the album, “The Promise (The Dolphin Song)”. In 1978, she’d canceled a tour of Japan after learning that fishermen were slaying dolphins off Iki Island. She later re-instated the tour when the Japanese government agreed to curb the practice. Featuring one of the most tender, heartfelt vocals of the singer’s career, “The Promise” raised awareness about the mistreatment of dolphins, especially by the commercial fishing industry.

“I thought it was a lovely song,” says Farrar. “I was sort of nervous about the way I should treat it because I didn’t want Olivia to be disappointed in what I came up with. I kept it very sort of simple and gentle.”

“The Promise” opened with the sound of waves lapping the shore. “We got a Nagra machine,” Holman recalls. “That was the machine that everybody used to record anything in films. It was very expensive at the time and a beautiful piece of machinery. John and I took some microphones and went down to the beach late one night. It was a silvery moon so we didn’t need lights or anything. We recorded the ocean for hours.” Recorded separately, the dolphins’ own chirps and clicks made a cameo appearance amidst the surf.

Farrar introduced the song’s wistful melody, employing a unique, aqueous sound to his strumming. “We put the guitar through a vocoder, and then I triggered the guitar with the ocean sounds,” Holman continues. “As John’s playing the guitar, the sound of the ocean actually shapes the guitar and makes it ‘sound’ like the ocean. What you’re hearing is the ocean in the background, and then you’re hearing that ocean also affect what the guitar sounds like. It all starts gluing together and becomes one piece.”

In the album’s sequence, “The Promise” closed Side Two, as Newton-John’s voice softly faded into the grooves. The album’s opening track, however, packed a punch seldom glimpsed on her records. “Landslide” was the perfect springboard into an album that announced the singer’s change in style. The song itself marked a detour from Farrar’s typical writing process. “I decided to try and write it from a keyboard, which I didn’t usually do,” he says. “I’m not a keyboard player. I had a keyboard hooked up with a vocoder and developed the song through that.”

Farrar excelled in fashioning a cutting-edge track for Newton-John. She quelled the song’s explosive introduction, bringing an equanimity to the first line, “Cold winds rarely blow, here at the end of the rainbow”. Throughout the track, Newton-John deftly drew upon a variety vocal gestures to navigate the song’s swirl of sounds. From the angelic harmonies that waft through the bridge to the tune’s hair-raising denouement, “Landslide” unveiled a newly invigorated singer, ready to rock.