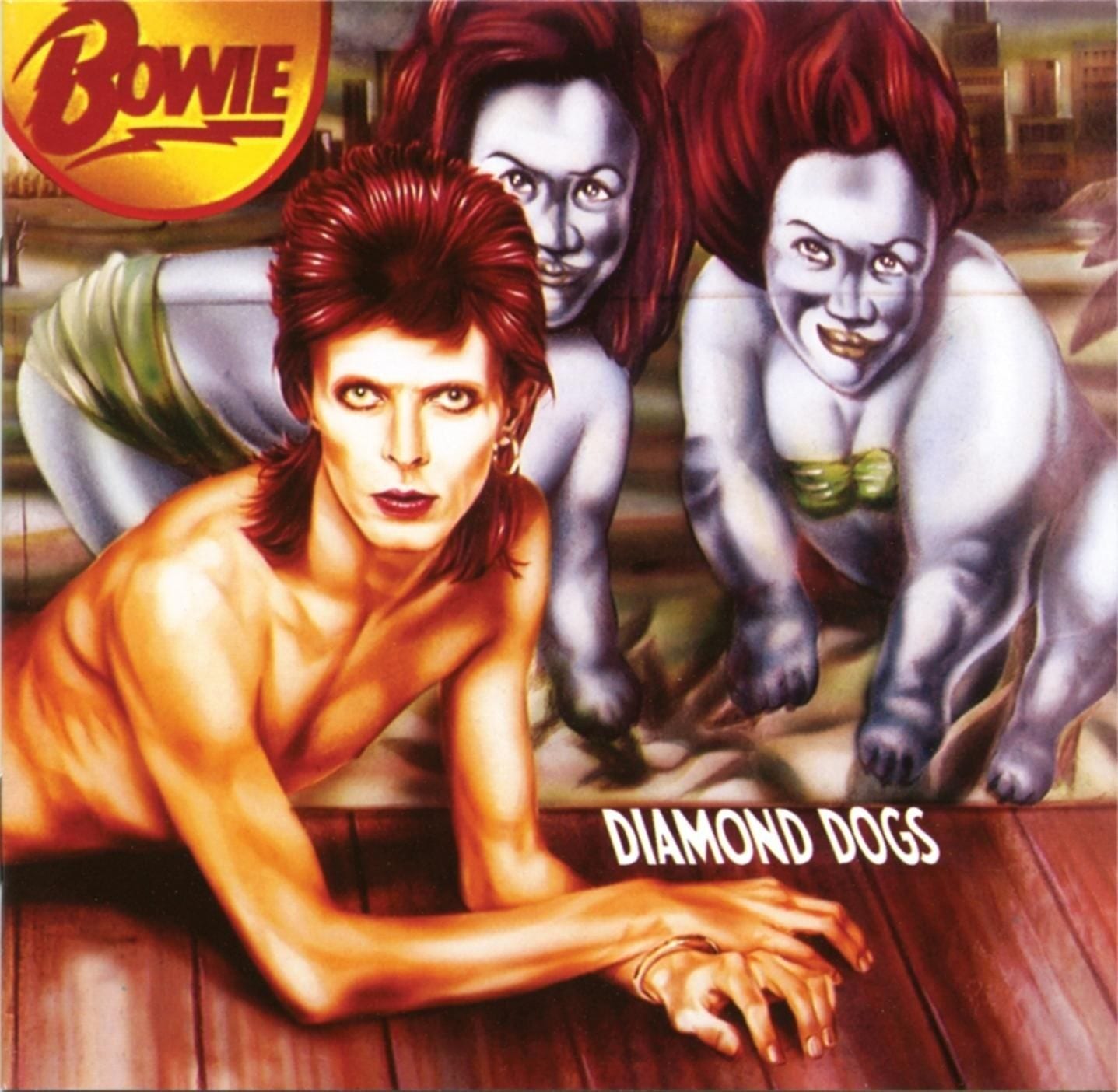

“Sweet Thing”/”Candidate”/”Sweet Thing (Reprise)” – Diamond Dogs (1974)

Back in dystopian mode, 1974 was the sound of the end of things, whether it’s the Ziggy persona, the glam years, human civilization, or the presence of Mick Ronson, whose departure left Bowie to handle all the lead guitar himself. “Sweet Thing” comes off like bedroom soul, but the song is actually a dark depiction of an urban inferno where the streets have claws and prostitutes lure boys into doorways where they find themselves “putting pain in a stranger”. The song is the full expression of Bowie’s vocal range, moving from his deepest bass at the beginning up to a squeal all in one verse, and when the Dame lets it loose, he makes like Liza Minnelli in the city of endless night. As for Bowie’s guitar leads, paired with Mike Garmon’s careening piano tumult around the three-minute mark, it’s a juvenile success, the sound of druggy and lonely diamond dogs holding hands and jumping in the river.

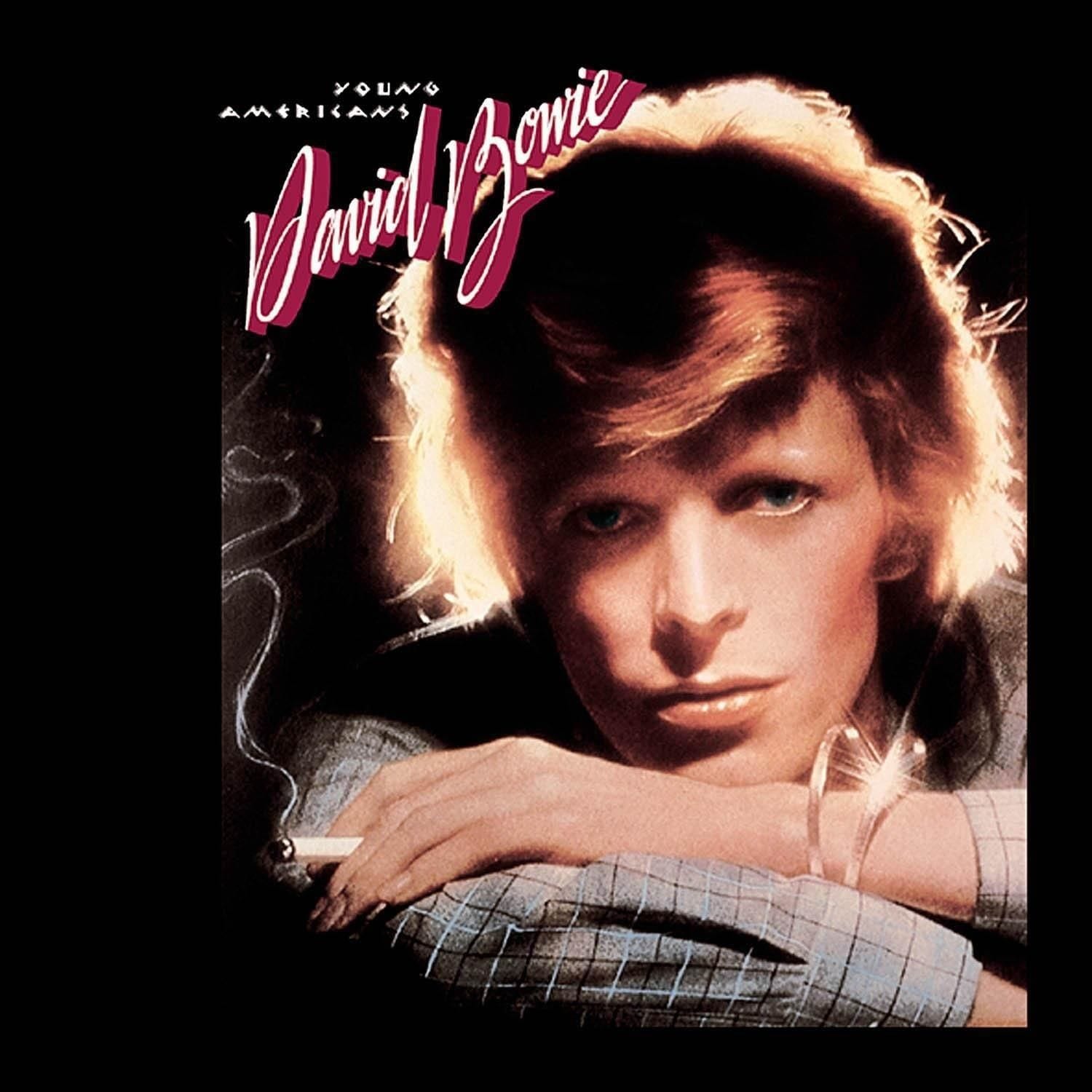

“Somebody Up There Likes Me” – Young Americans (1975)

From Bowie’s “plastic soul” period when he fell hard for Philly-influenced black music, hence the slamming “Somebody Up There Likes Me”, a standout track from Young Americans. Splitting the difference between Steely Dan’s jazz rock and Teddy Pendergrass-style R&B, “Somebody” is anchored by David Sanborn’s wailing alto sax and new-arrival Carlos Alomar’s watery double-tracked guitar figures. Bowie’s vocals are nearly unrecognizable as he tries to sound like a yankee soulman, singing with smooth restraint at first, then growling into the chorus and working himself breathless by the end. It’s another of his great, versatile vocal showcases, and that’s a young Luther Vandross chiming in on the responses. Bowie is taking on false prophets, cults of personality, and political swindlers, a theme that belies the below-the-waist groove in the music. As with everything he touched, even with Bowie imitating other genres, his own expression of blue-eyed soul spawned a new movement in Britain, and the album became his first smash hit in America.

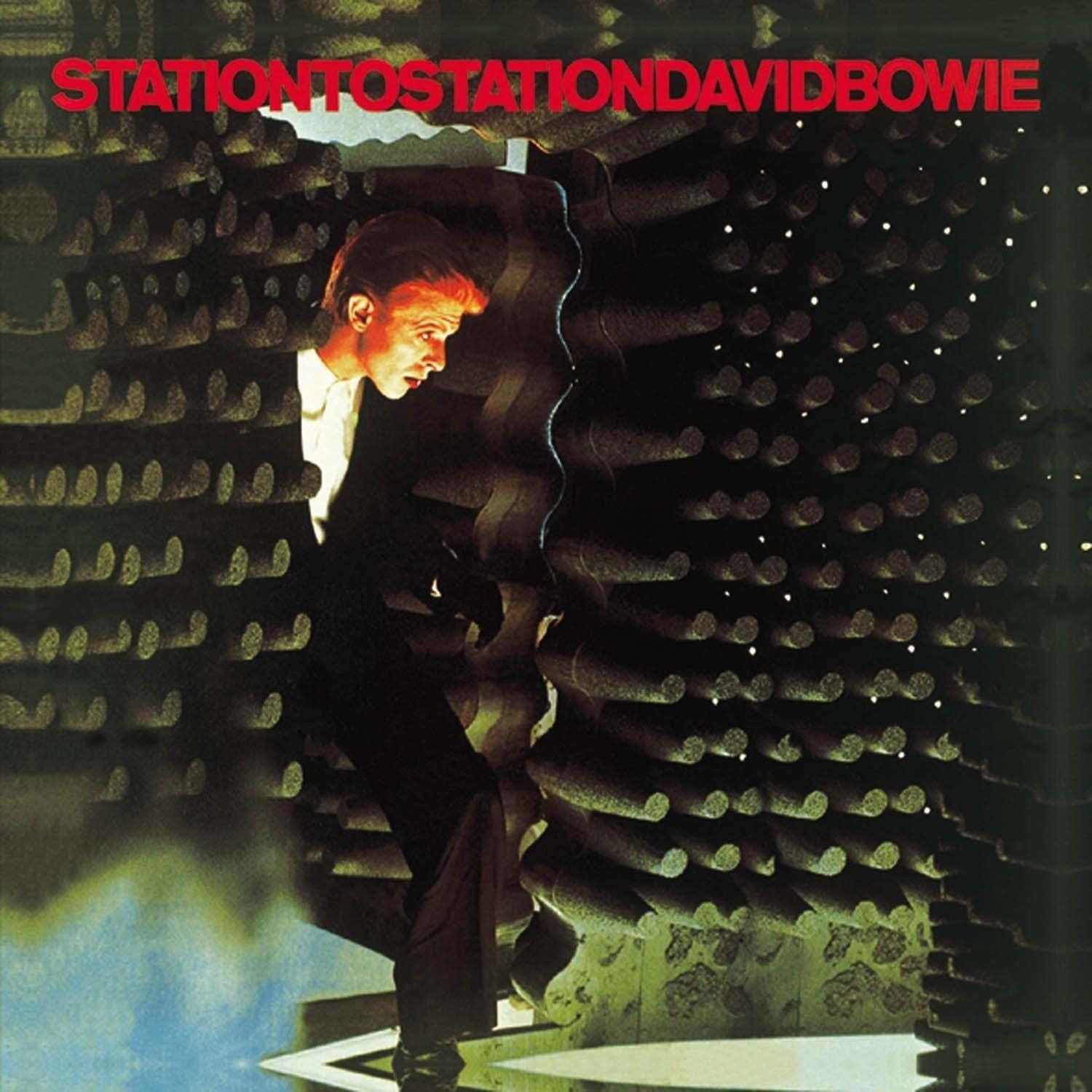

“Word on a Wing” – Station to Station (1976)

One of the most feloniously overlooked songs in the Bowie canon, “Word on a Wing” is a sweeping beauty. Sandwiched between uptempo hits “Golden Years” and “TVC 15”, the song has been a source of debate for Bowiephiles as its lyrics document Bowie’s flirtation with being born again. But whatever spiritual overhaul or commitment Bowie appears to be making here, he acknowledges his doubt: “Just because I believe, don’t mean I don’t think as well.” These were the Thin White Duke’s darkest days, a drug-addled time of tenuous sanity giving rise to an interest in fascism and black magic and, apparently, a desperate reach for a little help from above. Regardless, “Word on a Wing” is simply Bowie at his most gorgeous as a songwriter, six minutes of Bowie sailing his voice over waves of exquisite melodies featuring a series of knee-buckling key changes and E Street Band pianist Roy Bittan’s distinctive playing.

“Always Crashing in the Same Car” – Low (1977)

“Always Crashing” is a sultry Side One fragment that starts immediately with Bowie’s chill-pill vocals amid Brian Eno’s dark-side-of-the-moon synth swirls and Bowie’s Chamberlin hook. Dennis Davis’s muffled drums are set free for the first chorus, where his snare is run through a Harmonizer (thank you, Tony Visconti), and his kick drum creates a lub-dub heartbeat under a stellar second verse about Bowie hitting 94 mph in a parking garage. Ricky Gardiner’s fuzz-wank guitar solo stands in for the third verse, a very Low move. Bowie was escaping the coke-heavy L.A. scene by going to Europe to make the album, and the lyrics on “Always Crashing” use driving metaphors to describe Bowie’s repetitive rut, perhaps based on specific moments of Bowie hitting rock bottom. That sigh he lets out at the beginning of the second chorus tells the story. The song crashes into a final minor chord as though the long erotic night has ended and all that’s left is the hangover. Better put it on Side Two.

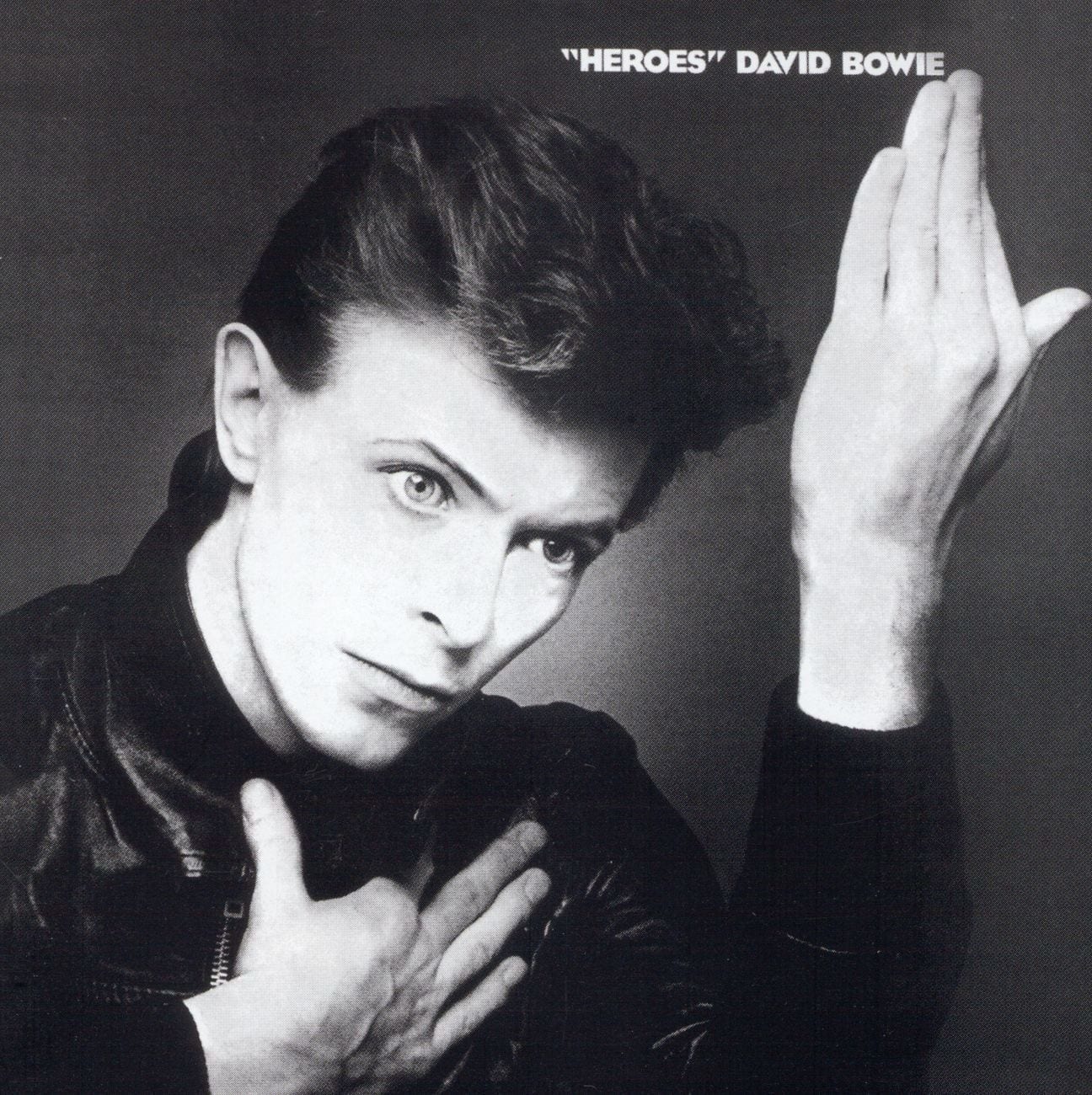

“Sons of the Silent Age” – “Heroes” (1977)

Coming after the menacing disco of “Beauty and the Beast” and the hopeful title anthem, but before the ambient instrumentals on Side Two (including the great Kraftwerky ode to German long-range ballistic missiles, “V-2 Schneider”) sits “Sons of a Silent Age”. It’s a sort of throwback for Bowie, as he returns to a Cockney accent on the bleak verses, incorporating an internal rhyme scheme and lyrical consonance: “Sons of the silent age / Stand on platforms / Blank looks and notebooks.” The chorus is big and round and romantic, sung in a wholly different voice, another example of the Dame’s tendency to piece fragments together into a single song.

“Heroes” might be Bowie’s saxiest LP, and his drowsy saxophone lines dominate the break between verses, while Robert Fripp’s heavily processed guitar blends with a thick wash of Brian Eno’s synthesizers. What Bowie’s on about is anyone’s guess, probably the lost, drunken souls Bowie observed while cutting the album a few blocks from Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin. In any case, it’s another reminder that Bowie was ruminating about death 40 years ago: “They never die / They just go to sleep one day.”

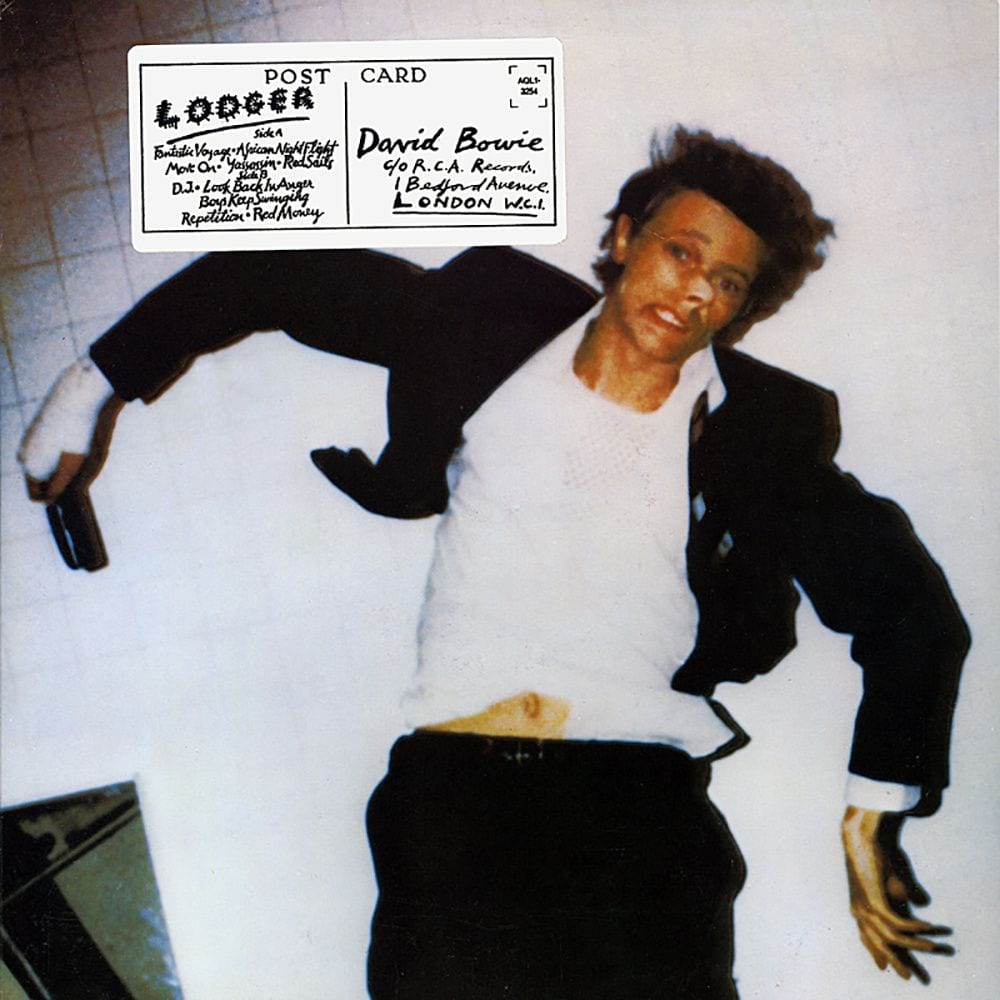

“Red Sails” – Lodger (1979)

A lost track from Lodger, the third in the so-called “Berlin Trilogy”, although the album was recorded in Switzerland. But Brian Eno is still onboard, and “Red Sails” has plenty of Eno’s sonic footprint, including those whirlpool synth clusters and guitar treatments. Bowie sings a bumblebee melody that spills every which way with what amounts to found poetry, using nautical imagery to describe the restless drive of an itinerant rambler. Carlos Alomar lays down a filthy rock-guitar riff (nearly losing the handle on it), and Dennis Davis mostly hammers away at the German-influenced motorik backbeat although he’s unable to resist breaking into some monster fills. And how about Adrian Belew who steps into play an awesomely crazed squall of a guitar solo over the final minute. By the end, Bowie has been on that thunder ocean so long, he’s gone postlingual, chanting himself loony and unable to even count to four properly. This might be the most underrated song on Bowie’s most underrated album.

- David Bowie: Young Americans

- David Bowie: The Next Day

- David Bowie: The Buddha of Suburbia

- The Great I Am: Magic, Fascism, and Race in David Bowie's 'Blackstar'

- Counterbalance No. 16: David Bowie - 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars'

- David Bowie: ChangesNowBowie

- 'What a Fantastic Death Abyss': David Bowie's 'Outside' at 25