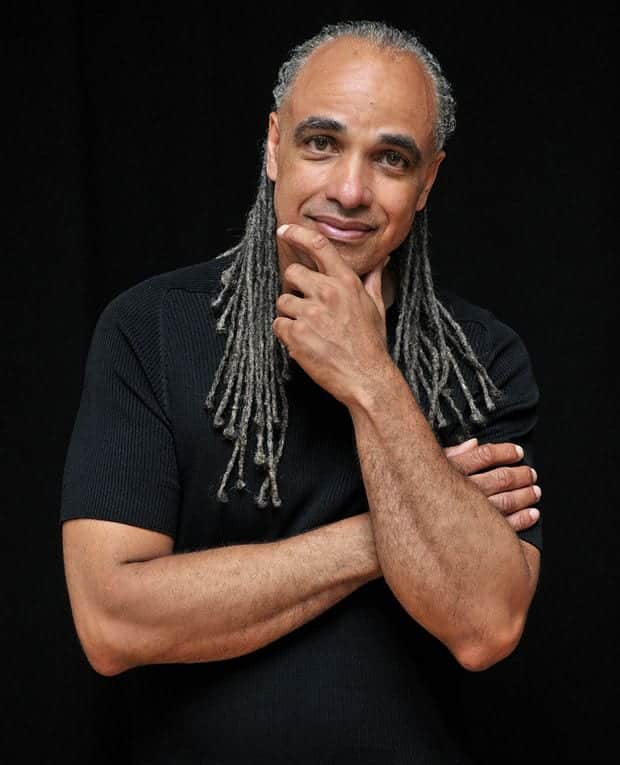

“My name is Mino Cinélu. Welcome to the party.”

Nestled along W. 3rd Street in Greenwich Village, the Zinc Bar turns into Mino Cinélu’s living room for nearly three hours on a frosty November 2014 night. He is the consummate host, presiding atop a cajon drum box that, by evening’s end, is likely left with a million fingerprint impressions. Whether singing, playing guitar, or deftly handling any number of percussion instruments he’s collected from around the world, Mino Cinélu’s multi-faceted musicality shines brilliantly.

At this particular performance, Mamadou Ba (bass) and Jamshied Sharifi (keyboards), both formidable musicians in their own right, join Cinélu’s World Jazz Ensemble, with guest appearances by Paul Carlton (sax) and Doug Hinrichs (percussion). Cinélu also instructs a few audience members on how to spin “windjammers” at one point. In Mino Cinélu’s living room, everyone is a star.

Just two months prior to this night, Cinélu brought his peerless musicianship to a considerably larger room for one of 2014’s most anticipated musical events: Kate Bush’s 22-date residency at the Hammersmith Apollo in London. It had been 35 years since Bush mounted a stage production, and Cinélu was among a select group of musicians who helped manifest Before the Dawn. “A magic of percussion,” was how Bush described Cinélu. “Always there with a big smile” (The Times, 28 August 2014). Hers is an accurate description, for Cinélu has long been a musical force who spellbinds audiences through his mesmerizing talent and a beguiling stage presence.

The seeds of that talent were planted during his childhood in Boulogne-Billancourt, a suburb west of Paris. Cinélu grew up in a two-bedroom flat with one sink that doubled as a basin for all five members of his family. Music was a refuge for young Mino as his parents moved him and his two older brothers north to Puteaux. Raised on a wide range of styles, from jazz to classical to the biguine music of Martinique, Cinélu mastered several musical dialects at an early age.

He left home before his 18th birthday and hitchhiked through the South of France before settling in Paris, where he landed his first recording sessions. He quickly became an in-demand player, traveling between France, England, the U.S., Italy, and Martinique.

By the time he turned 24, Cinélu had been living in New York City for two years, gigging with some of the city’s top players in jazz, funk, and gospel, when he was approached by a man who’d mark a major turning point in his life and career: Miles Davis. Beginning with the concerts that furnished the critically acclaimed We Want Miles (1982) album, Cinélu joined Davis’ band. “With Mino, any music swings,” Davis once said, offering his ultimate seal of approval. Cinélu would remain a loyal friend until the jazz icon’s passing in 1991.

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Cinélu’s profile continued to grow onstage and in the studio. He joined Weather Report for the group’s last two albums, including the Grammy-nominated Sportin’ Life (1985). Sting then tapped Cinélu to sing and play percussion on both the album and accompanying world tour for …Nothing Like the Sun (1987). The two would subsequently travel to Xingú in the Brazilian Amazon to meet Chief Raoni Metuktire of the Kayapó, which inspired Sting and Trudie Styler to establish the Rainforest Foundation in 1988.

Meanwhile, countless luminaries from jazz, pop, rock, and R&B sought Cinélu for recording dates and live gigs. Herbie Hancock, Branford Marsalis, Tori Amos, Marcus Miller, Tracy Chapman, David Sanborn, Anna Maria Jopek, Laurie Anderson, Pat Metheny, and Cassandra Wilson were just a handful of the artists who recruited him for a variety of projects over the next dozen years.

In between, Cinélu recorded full-length collaborations with Kevin Eubanks & Dave Holland (World Trio, 1995) and Kenny Barron (Swamp Sally, 1996) before releasing a pair of solo albums, Mino Cinélu (2000) and Quest Journey (2002). Cinélu also wrote scores for film and television, including the Oscar-nominated documentary Colors Straight Up (1997) and La Californie (2006), which earned him a nomination for Best Film Score at Cannes.

Acclaim and accolades from critics and peers alike have not curbed Cinélu’s quest to keep exploring the bounds of music. “The most challenging concert I do is where I’m challenging myself,” he says. “The hard part is to tell a story on the drums.” Like a sorcerer, he extracts sounds from drums and percussion, creating a sonic storyboard. The different dynamics and intensity of his playing evoke a range of moods. By the end of a show, Cinélu has not only challenged himself; he’s also told at least a dozen stories by the mere touch of his hands. In this exclusive interview with PopMatters, Cinélu reflects on the inspiration that’s fueled one of the most fascinating career trajectories in music.

When I saw you at Zinc Bar recently, I noticed how effortlessly you commanded the stage and connected with the audience. You have a regal presence yet you’re still very relatable. How did you cultivate that particular ability to draw and sustain a connection with audiences?

It’s second nature to me. I believe that being onstage is perhaps the place where I feel the most natural. I’m totally bare, but I’m also very comfortable. It’s a strange thing between strength and fragility. The more you know me, the more you know it’s part of me. I can be very serious. I can be extremely silly as well. I’m truly the same onstage but of course with the adrenaline it’s developed a lot more. I believe that if we’re onstage, if we give what we call “a show”, then we’ve got to connect with the public. At that moment, there is a very strong communion with everybody. The spirit is amplified by the sheer number of people. It’s something really incredible. The trap is that sometimes you can never get out of it, to bring it down to reality. What happened onstage was real but it’s not “real life”. You make the voyage what you want it to be, I would say.

Tell me about your first memory of performing onstage.

I can’t even remember the very first time. It’s so long ago. I remember playing with my two brothers who are older than me. There was a feast somewhere in the south of France. We were on vacation; I must have been ten years old. The three of us were with guitars and only two microphones. One mic was right in front and the other mic was behind. My brothers both went for the mic in behind so the choice for me was to freeze or to go to that mic in front. I was half trembling but the desire to play was way stronger than fear. From that day on, I conquered most of the stage fright.

Let’s go back even further. What is the significance of your name?

My name is Dominique, actually. The name “Mino” exists because I’m the youngest in my family. It’s the name that I put on my French passport. It has a lot of significance because, as the youngest, I also represent the next generation. “Cinélu” sounds Romanian, so I’m sure there’s gypsy blood in me because of my mother’s side. My great-great grandmother was from Portugal. My father’s from Martinique. There’s Indian, Chinese, blood from Brittany and of course from Martinique, mixed with black and white. His father was very dark, so my guess is he’s from Central Africa. On my mother’s side, there’s Parisian with blood from Brittany and blood from Portugal. The blood from Brittany is very strong.

I’m really very secure in who I am. I’m mixed. It gave me strength. Often, I was the only non-white in school. To them, I looked Arabic and they gave worse treatment to Arabic-looking people in Paris.

Some of the Middle Eastern cafés were open late at night. I used to go over there with my bongos to jam with them. That made me feel close to them. They had some kind of jukebox with video. You could listen to Farid El Atrache, Om Kalsoum, Mohammed Abdel Wahab. Music literally saved my life. Without music, I probably never would have made it.

Your father was born in Martinique. What brought him to France?

He was a sailor in the army. He did the Indochina War and traveled the world. Many people from Martinique and Guadeloupe and all those Caribbean islands came to the metropole, which was France. He was one of them, basically. I can’t imagine what he had to deal with.

My father was a musician. He was a singer also. He loved to dance the tango so my parents used to dance. My mother could sing. We used to listen to music all the time, any kind of music. I have to thank my father for that. It was a lot of classical music, mostly baroque, but also jazz: Satchmo, Ella Fitzgerald, Dave Brubeck. Not so much Miles, interestingly so — I’m not sure why, to be honest. My father also used to listen to biguine, which came from Saint-Pierre in Martinique sometime during the early 1900s. It was influenced by European music, especially polka! I believe that what they used to call the “Orchestrated Biguine” was the kind that possibly influenced New Orleans jazz. Of course, it also inspired Artie Shaw’s famous arrangement of “Begin the Beguine”, composed by Cole Porter.

When I went to Martinique the second time, I’m the one who fetched an album of the roots music from the island. I brought that to my father on his birthday. That’s the first time I saw him dance like that! I said, “Oh wow, he’s really from Martinique!” I struck a nerve, obviously. He looked at the album. He could not believe it was Ti Emile. Actually, this singer really influenced me quite a bit. It’s traditional ladja bélé dancing, which is the fighting dancing that we have on the island. It’s like capoeira but a bit harsher. “Ladja” means war, and then “bélé” is the drum.

I know you played guitar before you learned drums and percussion. How did you feel the first time you held a guitar?

I was about eight years old. I felt like my life would change because I felt like this creature truly understood me. Perhaps it was my first encounter where something became someone that would listen to whatever my soul had to express, without judging. It was always ready to be bounced back in a positive way. I was a loner. When I was not able to play the drums at night, I’d isolate myself and play guitar. I’d be six years old and go into the woods at ten o’clock at night, and just sit against the tree and listen to the sounds of the night. The guitar saved my life. Every time Kevin Eubanks sees me play, he says, “Look at Mino! He’s an animal on the drums but he’s the sweetest thing when he plays the guitar.”

At what point did you start playing drums and percussion?

My two siblings are older than me. Sometimes we’d have three guitars or two guitars and something like a flute or a recorder, whatever we could grab to play music. In order to make a band, we needed some rhythm. They weren’t as dedicated, I guess, as I was with the rhythm so it just happened. Someone has to do it, so why not me? I didn’t have a drum set for a long time. I once talked to Ray Angry, the keyboardist. I said basically I believe in the strength of the mind. If you truly strongly imagine and feel that you’re playing that instrument or practicing that instrument, then you are doing so, in a way. It works to a certain point.

The self-titled album by Moravagine was recorded at Studio Palm in Paris, December 1975. That seems to be the first instance of you on a record.

That was one of my first recordings; not the first, but the first one where I played percussion. That band asked me to become a percussion player. Moravagine is also a novel by Blaise Cendrars.

The album is such a fascinating fusion of styles… jazz, classical. You’re given some great moments to shine on tracks like “Zabuco”. I love the photo on the back of the album cover.

You saw that? (Laughs) Was I ahead of my time or what? We were all kind of hippies. I had this silver fork bracelet. We had those rings that we called tiger eyes. I had, at that time, some kind of very light Indian scarf. The hat I must have found in a flea market. That jacket was gold mutton. We didn’t kill the thing. I think they just shaved the wool. That was the vibe.

In that photo, you radiate such star quality.

I was new. I brought trouble! (Laughs)

When did you first visit the U.S.?

The first time I came was before I went to live in England. It was, I think, February 1976. I was with an artist named Toto Bissainthe. She was a singer, actress, and activist from Haiti. I played with her in a trio. This time I was playing both drums and percussion and singing background vocals for her. She asked me if I wanted to come to New York. I said sure. I didn’t know yet, but she was huge over here because of the Haitian community. We played Carnegie Hall. That was the first gig I did in America; it was incredible. I couldn’t speak English at the time. When we arrived at the hotel, it was the first time in my life that I’d seen so many black people in cold weather!

Then I returned to France. I was looking for change. I’d already recorded about three or four albums with some artists, modern jazz and fusion. I recorded with Toto Bissainthe and a singer from Gabon, Pierre Akendengué. Interesting voice. He was brilliant. I wanted to challenge myself outside of the music scene in France. I went to Italy. I went to Martinique several times to work with the top guys. Then I went to England. There was a group called Gong…

Right, the Gazuese! (1977) album! I love the track “Esnuria”!

It was interesting. Steve Winwood saw us play live and he said, “I want to join the band. Whatever you want. You want me to sing? Play guitar or keyboard?” To my surprise, the band members declined his offer.

I stayed in England about close to a year. Afterwards, I was back in France playing percussion with a soul band from the U.S. called Ice. They said, “We’re going to New York.” I bought my own ticket. I came here as a tourist and jammed with musicians all over New York.

After I came to the U.S., I played traps with a soul band called Frank & Cindy Jordan. They came from gospel. It was a vibe like Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell. Cindy was truly exceptional. By working as a trap drummer, I felt I was losing my skill on percussion. I said, “Do you mind getting a drummer and I will play percussion?” They said, “Do you want to leave the group?” I said, “No I just want to play percussion. I’m rusty with it.” They’d never heard me play percussion, just traps. They trusted me so I switched to percussion. They got a drummer just before the gig at Mikell’s.

Mino Meets Miles

And that Mikell’s gig is where Miles Davis first saw you.

Do I have the luck of the Irish or what? (Laughs) Long story short: We play on stage. I think Ashford & Simpson were there that night. There was a guy in the front row looking really really intense. He was listening to the music like no one else in that club. The set finished. This guy grabs my arm; he’s really strong. He looked older. You could not recognize him, especially because he was not in the best of health. He said, “You’re a bad motherfucker. Give me your number.” I tried to move away, not really to defend myself but I was sensing the situation. I said, “My name is Mino.”

Then there’s this big circle around us. Is everybody going crazy or what? Pat Mikell, the owner of the club, tapped on my shoulder. She said, “Do you know who that is?” I said, “No, but I introduced myself.” She said, “This is Miles Davis.” I went downstairs, changed, and got paid. At the time, I had some business cards that I cut up myself. I came back upstairs and he was waiting for me. I gave him my card. He said, “Thank you. You’re a bad motherfucker.” One week later, the phone rings and it was him. “Come to the studio immediately. I’ll pay for the taxi.” But where? The phone rings again. “This is Bill Evans. I’m the sax player. This is the address.” I arrived at Miles’ place on W. 77th St.

Before you met Miles, what were your impressions of him?

It was more the fusion music I knew first, On the Corner (1972), Bitches Brew (1970). I came to his older music later on. Interestingly enough, I was a teenager and I remember saying, “One day I know that if I meet Miles, then we’ll play together.” That was not a goal but it was something that made sense. When it happened, it felt right to me. I had no doubt that it would happen, somehow.

Miles’ health wasn’t top then. He almost died of pneumonia in Tokyo in 1981. He was in so much pain so often. I used to massage his hands before some concerts. He had issues with his hands. I’ve learned many ways to heal and preserve my own hands, so I helped whenever I could. At the end of the massages, he used to say, “Thanks Frenchy”.

I love that you were able to perform with Miles on the Grammy Awards in 1983 when he got the Grammy for We Want Miles (1982).

Everybody was there. Quincy Jones, Donna Summer, Grace Jones, Rick James, Lionel Richie. You know who presented the Grammy to Miles? Ella Fitzgerald. Ella Fitzgerald sat right there. I’m looking at her. She comes to me, embraces me, and says, “You were great!” When you talk about the American dream for people, at that time, it was a cadillac and a house. To me, it was to be acquainted with musicians of this caliber, and I was. I was embraced by those people.

You toured with Miles and recorded a succession of albums with him — We Want Miles, Star People, (1983) and Decoy (1984) — before joining Weather Report. Though you’d perform with Miles again throughout the ’80s, how did you make that initial transition from his band to Weather Report?

I was approached by Omar Hakim and Victor Bailey. They saw me play with Miles and also with my band at Mikell’s years ago. At first, I was playing with both Miles and Weather Report. Miles was fine with it. He knew at some point I had to make a choice. On the road with Weather Report, Miles called for me. I was in Italy somewhere in some hotel room. He said, “Where are you? What are you doing?” He knew exactly what I was doing. I said, “I’m with Weather Report.” You know what he said? He said, “Those are my children.”

That’s quite a compliment.

That’s nice, huh? We talked. We never spoke more than five minutes on the phone because of my accent and his! (Laughs)

Describe the creative dynamic between you and Weather Report.

I was blessed because they gave me carte blanche. The challenge for me was to fit into the band. With Miles, there was more space, I would say. In Weather Report, Omar is a very active drummer. I was surprised when they called me. By searching, I started to develop more of an ensemble sound. I started to learn this drum feel with all of these other instruments. I believe I was the first to use electronic percussion in Weather Report. It didn’t conflict with Joe (Zawinul). He was Mr. Electronics! What was helpful was that I also had knowledge of other music. When Joe was talking about his roots, some of the Eastern European music, I was aware of all of that. “Where are you from, Mino?” (Laughs)

Sportin’ Life (1985) was the first Weather Report album that featured you in the lineup. It’s pretty amazing that you’re the new guy and yet they included a completely self-penned song of yours, “Confians”.

Joe asked me if I had a tune he could hear. I didn’t realize that perhaps it would be featured on the album. I had “Confians”; it was a demo, a cassette. I played it. “We’re gonna do this on the next album.” I said, “Really?” Joe said, “Who’s playing keyboard?” I said, “That’s me.” “Well I’ll play keyboard. Okay sure! It’s incredible because Victor wasn’t there so I played some scratch bass. I played the bass, the guitar, and the drums on “Confians”.

Years later, you recorded a solo version of “Confians” and also did a couple of remixes. It’s become a staple of your set. What was the inspiration behind “Confians”?

The lyrics came in one night. They’re written in Creole from Martinique with a few expressions from Guadeloupe and a few words from Haiti. The lyrics are really about me following a dream. For so many years, I was crushed by my folks. I had to leave. I left home for Paris with my drums and my bongos and my guitar.

I used to play in the streets. I used to steal food. I didn’t always sleep on a bed. I expressed all of who I was through the music. Those lyrics talk about the struggle.

You also sing on “Confians”. What does singing give you that’s different from playing?

Singing is perhaps the most challenging thing I do, because it’s never guaranteed. There are some very talented people who are naturals. They never practice but they can sing well no matter when. I’m not that kind of person. Singing is another beast. To sing and play the drums very strongly like I do is impossible. Singing is something that I, personally, cannot control. You’re beyond naked. It’s an incredible feeling. With singing also comes the lyrics so you’re talking about an aspect of music that no instrument can touch. In that aspect, it’s pretty unique. Miles wanted me to sing, actually. He was into Prince at the time. One of the tunes was “Chocolate Girl”. We’re on the phone one time. He asked me, “Can you rap in French? Sing something in French.” “I got to sing in Creole.” “I don’t want it in Creole, I want it in French!” I did the rap in French. It was before You’re Under Arrest (1985). He called me to do it. Sting was in the studio so he was the one who did the rap. It’s difficult to compete with him! (laughs)

A few years after the last Weather Report album (This Is This, 1986), you performed with Herbie Hancock at Montreux Jazz Festival. I love what he said in his introduction: “You see these things over here? They look like toys to me but in the hands of a master, they’re not toys. The master I’m referring to is Mino Cinélu.” How was performing with Herbie different from all the other greats you played with?

It’s hard to compare those people. The difference is that Herbie is like a kid. It’s like child’s play. He’s a true Buddhist. He truly believes. His spirit is incredible, very positive. He has that thing that you will give your best; he’ll just give it all and more. He does it in a relaxed way. He used to come and see us with Miles.

Interestingly enough, that was perhaps one of the times where I said, “I wish to play with Herbie”. I’d never seen Miles play before I played with him. I first saw Herbie play when Headhunters toured Europe for the first time.

You recorded World Trio (1995) with Kevin Eubanks and Dave Holland. Then, 15 years later, The New York Times remarked that the album “Holds up and then some: it’s a model of collective rapport with a world-music twist, fully acoustic but crackling with energy” (30 May 2010). That’s a great testament to the three of you. What’s the origin of that project?

Kevin invited me two times to play with his band as a special guest and he was also a part of my band. He’s so brilliant. One day I said, “Why don’t we do a duet?” At the time, Kevin was more comfortable in a trio. He said, “How ’bout I call Dave Holland?” I said, “Twist my arm” (Laughs). I started to rehearse with Kevin in the place I used to have in Brooklyn years ago. Dave came and joined us; he’s a great player. He’s also a rhythmical guy. I was surprised. I didn’t know that about him. Very solid.

Kevin, of course, I knew. He’s a master. Everybody brought ideas of tunes. We just played. Maybe after one week or something like that, one of us would say, “By the way, what’s the time signature on your tune?” “It’s 4/4.” “What?” “Well, what do you hear?” None of us knew the time signatures, except for a few songs! I talk about that in the workshops that I do. What is right and what is wrong is very subjective. The outcome is what counts.

The constant in your career seems to be collaboration, collaborating with so many people from so many different worlds of music. Did it feel gratifying to have your own solo album when you signed with Blue Thumb for Mino Cinélu (2000)? Did you feel ready?

If I had to follow my belief, I would never be ready. The first time I was proposed to sign was by Virgin Records when I was in England. I said no. Even before that, I was playing with the Jef Gilson Orchestra (often referred to as “the French Gil Evans”); I was the youngest big band drummer in France and they offered me my own album. To me, I was not ready and I wanted to explore more and play with more people. It may not have been the smartest decision.

Even Miles pushed me: do your own thing.

How was recording Quest Journey (2002) different from your first album?

I think Quest Journey is the first album I mixed entirely. I tried to do something so ambitious. I had no choice but to learn how to do it myself. The first album, the eponymous album, was all recorded at home. It took a long time. That’s the first album that Pat Thrall mixed. Pat used to be the guitarist for Meat Loaf. He’s a great producer. He’s the one who taught ProTools to many engineers who were about to lose their job, short of learning this new technology. He was very kind to do that. I said, “Okay let’s mix it.” He said, “Once a day.” I said, “Once a day what? One tune a day to mix? Are you kidding?”

Actually, depending on the complexity of the mix, that’s pretty much the norm. It depends on the music but when you’re mixing digitally like it’s done now, if you do two tunes a day, you’re doing a good job. I was flabbergasted — “My goodness, I will grow old with this thing!” — but I remained open. Mixing on my own helped me appreciate even more what Pat did on my first album.

I was more into electro on Quest Journey. By that time, I was curious about techno music. A friend of mine said you got to check it out. To me, it was fast noise, but this guy’s older than me so if he’s open to it…

In every music, you’ll find something you’ll like. Quality is quality; it’s in every art. I started to listen again to very old Kraftwerk. All of this started to intrigue me. I got into sampling. I mixed everything I liked. It’s “electro-jazz”, whatever you want to call it.

“Feels Like Winter” features Toni Smith on vocals. Of course, a lot of us know her as the voice on “Funkin’ for Jamaica” by Tom Browne. What inspired you to record her singing on the track?

I’d hired Toni Smith for other productions that I was doing, even though she’s not known to sing ballads. I liked her so I thought let me just try and we did it. Toni thanked me. She said, “Mino, nobody ever calls me to sing ballads.” I think I have that talent to embark people on avenues they’re not used to going. To me, it’s a way to break the automaticism. People see me as a percussion player. They don’t imagine that I also write for films or that I played drums for many many years before I touched percussion. People see you in one thing. Whatever habits you have, you will break them if you do something you’re not used to doing. I’d love to get everybody to perform on something they’re not known for.

One of my favorite songs of yours is “Pwotéjé Nou”. I especially loved the rendition you did at Zinc Bar with keys, bass, and percussion; you sang and played it with such passion. What’s the background of that song?

This song is like a prayer, but without any religious intent. This piece was written after my first trip to Xingú with Sting in 1988. It was before Sting and Trudie Styler began the Rainforest Foundation. In “Pwotéjé Nou”, I say, “Don’t forget us. Protect us.” I say in Creole, “Sir Raoni, you truly are my brother, you too shall overcome, I truly believe.” Raoni is the head Chief of the Kayapó in the Amazon.

That reminds me, I saw some photos of you and Sting visiting the village of the Yawalapiti. There’s this great shot of you sitting in the center of the village playing a metal pot.

That’s part of the first trip to Xingú. There were some pots and pans. I started to play. Raoni was there, and all the kids came. I met one of those boys two years ago. He said, in Portuguese, that I taught him drums. He said, “Were you in the village of Aritana?” Aritana is the chief of the Yawalapiti, the village where we were. He said, “You taught me”. This was 1988 and he remembered my name!

I also saw Raoni two years ago in Paris. He’s an old man. His nephew Megaron was with him. He’s going to become the new chief. Raoni said, “You got to come back. You are now like my son.” Raoni is still Chief of the Kayapó and is fighting the destruction and industrialization of the Amazon, especially the construction of the Belo Monte dam on the Xingú River.

In May 2014, you spoke at the ceremony for the unveiling of “Miles Davis Way”, which is W. 77th Street between West End and Riverside Drive. How did it feel to be there?

I was very moved to be able to speak there. I got people laughing. I was myself. I was thinking vividly about the first time I went to Miles’ house. I remember another time him calling me saying, “You should come this afternoon.” “Why?” “I’m cooking!” It’s easy to fall into the mysticism but my voyage with him was really clear and really deep. I had no agenda. He truly understood me with no judgement. He was brilliant. I was just happy to be there. It’s hard to explain. All those memories came to my mind. I didn’t feel his spirit but I thought about him and by thinking about him, I know he had a good laugh!

You’ve had so many extraordinary experiences. When you close your eyes at night, which one do you think about the most? What do you re-live in your dreams?

It would be many things. Music always saved my life. This particular moment was perhaps one of the first times: I was around 17 years old, hitchhiking through the south of France with a pair of bongos that I stole from the conservatory. They were new and nobody ever used them. I felt that I had no other choice if I was going to panhandle on the streets of Bandol. I knew it also was a practice, a preparation for a new facet of my musical palette and my first recordings as a percussion player.

I remember there was another guy on the road hitchhiking. I said, “If you’re not a girl, nobody will pick you up at night.” He said, “I know.” I said, “Why are you in such a hurry?” He said, “Because there are gypsies over there. At night they’re going to cut your throat and take your money.” I looked at him and asked, “Why? Do you have money?” Because of the way I looked, he turned green! (Laughs) I didn’t have a bag to sleep on so I was sleeping with my head against the bongos. He said, “What about you? What if the gypsies come?” I said, “I’ll ask if I can play with them.” I think about that often. Just by being a musician, that calms people. It is a power. We should not take it lightly. Music is far more than just notes.